This guide to designing your course, regardless of teaching modality, is built on a framework known as “Backward Design." It explains the stages of Backward Design and provides suggestions for identifying learning objectives, planning a learning module, and, finally, designing your course syllabus.

Backward Design

Most faculty have used a “forward thinking” approach to course design – first, identify or develop materials and activities for teaching, then design assessments to measure the teaching outcomes. Forward design is a chronological way to create course materials, presentations, assignments, and assessments. Many researchers have challenged this process by pointing out that the “forward” design's focus is on the teaching process and not the learning outcomes.

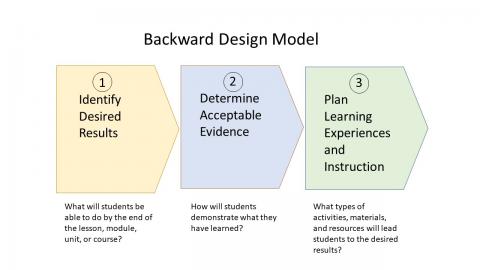

In their book, Understanding by Design, Wiggins and McTighe (2005) offer a different course design framework called “Backward Design.” Backward Design has three stages.

- Stage 1 focuses on identifying the learning outcomes at the course level and the learning objectives for each module, unit, or topic.

- Stage 2 involves designing and developing assessments to measure student performance with regard to the learning objectives from Stage 1.

- Once the learning outcomes/objectives are clear and assessments are confirmed, you will move to Stage 3 with a better idea about what type of instructional activities best align with these outcomes/objectives and will help students to be successful.

Understanding by Design, Grant Wiggins' two-part video series

Syllabus Design

Your course syllabus communicates your course design and expectations to students.

Consider adding the following resource information to your syllabus, as appropriate for your course: UNH Syllabus Template.

Review the resources regarding AI policies on the Academic Affairs Office of the Provost site above (UNH Syllabus template).

This is an additional Stanford University which provides sample course policies and informative resources on AI policies in your course.

In addition, here is a resource on AI detection Software Best Practices developed by Teaching and Learning Technologies.

Backward Design, Cell Biology course,

MSU Graduate School

To apply Backward Design planning in your course, use this Backward Design Template (in the Downloads section, select Design tools and download the latest UbD Unit Template).

Learning Objectives

Think about the kind of learning that your students should be able to demonstrate after completing a component of your course. Do you want them to explain a concept? Apply a theory? Evaluate a business plan? Solve a complex problem?

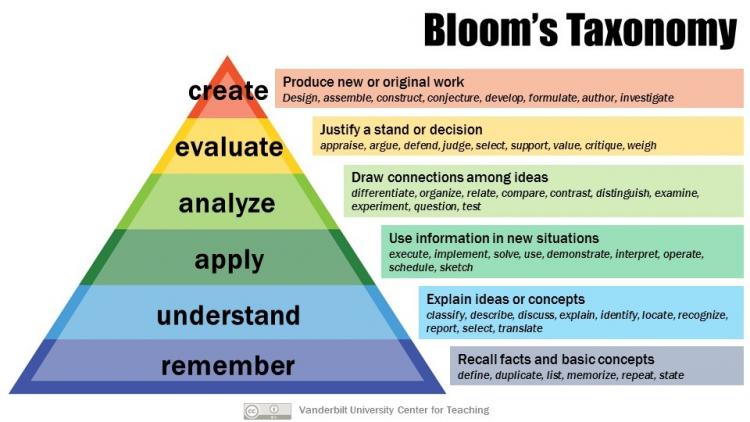

Bloom’s taxonomy (Bloom et al,. 1956) is one of the most widely used frameworks for categorizing learning outcomes. The original taxonomy included six levels of learning: Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis, and Evaluation. In addition to the initial focus on the cognitive domain, taxonomies were later developed for the affective and psychomotor domains. The taxonomy for the cognitive domain was revised (Krathwohl, 2002) to use verbs, rather than nouns, to define the levels: Remember, Understand, Apply, Analyze, Evaluate, and Create.

Once you identify the level of expertise, use appropriate verbs corresponding to the levels of Bloom’s taxonomy in the appropriate domain to construct your learning objectives.

Learning objectives should be student-centered; that is, they should express what the student will be able to do after completing instructional activities. Objectives should be clear, concise, and measurable. A measurable objective is described with observable action verbs.

An objective, “Understand the differences between x and y” is not sufficient in that there is no way for you, the instructor, to directly measure understanding. You can only observe actions that demonstrate understanding.

Instead, the objective might be rephrased: “List the differences between x and y”. Or, for a higher level of learning, “Explain the differences between x and y.”

In the case above, “List” might be assessed through a simple multiple answer or short answer quiz question, whereas “Explain” would require an essay, mind map, or presentation. Think about how you will assess student learning and phrase the objective appropriately.

Pay close attention to crafting good learning objectives when you outline your course. Doing so not only directs student efforts during the course, but also assists you in aligning your assessments while developing the instructional module. Gronlund (1991) provides detailed guidance on writing learning objectives for all domains (cognitive, affective, and psychomotor).

Lesson/Module Planning

When the learning outcomes at the course level and learning objectives at the module level are identified and assessment methods are established, we move to the last stage of Backward Design. In this stage, you develop learning activities and plans to provide students with the resources and information necessary to achieve the course outcomes and module objectives.

How should you organize your course content within a module? What kinds of teaching and learning “events” will support student success? Gagne’s Nine Events of Instruction and research on constructivist learning environments and content chunking all provide useful guidance.

Lesson/Module Planning Resources

Nine Events of Instruction

Gagne proposed nine instructional “events” that elicit a series of internal mental processes that support learning (Gagne, Briggs, and Wager, 1992).

|

Instructional Event |

Internal Mental Process |

|---|---|

|

1. Gain attention |

Stimuli activates receptors |

|

2. Inform learners of objectives |

Creates level of expectation for learning |

|

3. Stimulate recall of prior learning |

Retrieval and activation of short-term memory |

|

4. Present the content |

Selective perception of content |

|

5. Provide "learning guidance" |

Semantic encoding for storage long-term memory |

|

6. Elicit performance (practice) |

Responds to questions to enhance encoding and verification |

|

7. Provide feedback |

Reinforcement and assessment of correct performance |

|

8. Assess performance |

Retrieval and reinforcement of content as final evaluation |

|

9. Enhance retention and transfer |

Retrieval and generalization of learned skill to new situation |

Specific methods can be employed for implementing each of the nine events. For example:

- To gain students’ attention, introduce novelty, uncertainty, and surprise, or pose thought-provoking questions.

- To provide learning guidance, use examples and non-examples or provide case studies, visual images, analogies, and metaphors (Northern Illinois University Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning, 2020).

Because specific methods can be associated with each of Gagne’s events, the Nine Events of Instruction provides a useful framework for designing a learning module.

Components of Constructivist Learning Environments

Constructivist learning environments are built on the theory that students construct knowledge rather than just passively take in information. As they experience the world and reflect upon those experiences, students build their own representations and incorporate new information into their pre-existing knowledge (schemas). Students learn best when engaged in learning experiences rather passively receiving information.

- Learning is inherently a social process because it is embedded within a social context as students and teachers work together to build knowledge.

- Because knowledge cannot be directly imparted to students, the goal of teaching is to provide experiences that facilitate the construction of knowledge (University at Buffalo Center for Educational Innovation, 2021; emphasis added).

Baviskar, Hartle, and Whitney (2009) describe essential components for designing constructivist learning environments:

- Elicit prior knowledge. New knowledge is created in relation to learner’s pre-existing knowledge. Lessons, therefore, require eliciting relevant prior knowledge. Activities include: pre-tests, informal interviews, and small group warm-up activities that require recall of prior knowledge.

- Create cognitive dissonance by assigning problems and activities that will challenge students. Knowledge is built as learners encounter novel problems and revise existing schemas as they work through the challenging problem.

- Apply knowledge with feedback. Encourage students to evaluate new information and modify existing knowledge. Activities should allow for students to compare pre-existing schema to the novel situation. Activities might include presentations, small group or class discussions, and quizzes.

- Reflect on learning. Provide students with an opportunity to demonstrate what they have learned. Activities might include: presentations, reflexive papers, or creating a step-by-step tutorial for another student.

Content Chunking

Content chunking is a method by which a large amount of information is organized into manageable pieces in order to help students to retain and recall information more effectively and efficiently.

Miller (1956) claimed that our short-term memory could hold only seven, plus or minus two, chunks of information. In practice, depending on the complexity of your material, you may want to consider minimizing the chunked material into three to six pieces for better comprehension.

How do you apply this to your course? When mapping out the course structure (units, modules, lessons, etc.) and when designing teaching and learning materials:

- Prioritize: Determine the main ideas and supporting content.

- Simplify: Retain relevant course content and remove extraneous content. Use visuals and other media in place of text when applicable to lessen the load on working memory.

- Organize: To provide organizational cues and minimize cognitive load, use:

- Bulleted and/or numbered lists

- Short subheadings

- Short sentences with one or two ideas per sentence

- Short paragraphs, no more than three to four sentences

- Easy-to-scan text, with bolding of key phrases

The SlideShare presentation, Basics of Content Chunking (Marican, 2014) demonstrates the process by which complex information can be better organized by chunking.

See these articles that discuss content chunking strategies along with techniques that can be applied to course development:

Chunking Information for Instructional Design

Applying content chunking for organizing modules, lessons, and topics.

4 Tips For Content Chunking In e-Learning

References

Baviskar, S. N., Hartle, R. T., & Whitney, T. (2009). Essential criteria to characterize constructivist teaching: Derived from a review of the literature and applied to five constructivist‐teaching method articles. International Journal of Science Education, 31(4), 541-550.

Bloom, B. S., Englehart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). The Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook I: The Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay Co., Inc.

Gagne, R. M., Briggs, L. J., & Wager, W. W. (1992). Principles of Instructional Design (4th ed.). Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers.

Gronlund, N. E. (1991). How to Write and Use Instructional Objectives (4th ed.). New York: Macmillan Publishing Co.

https://unh.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01USNH_UNH/121i3ml/alma99…;

Krathwohl, D. (2002). A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: An Overview. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 212–218.

https://unh.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01USNH_UNH/1o8seis/cdi_proquest_journals_218799120

Marican, F. (2014). Basics of Content Chunking (slideshare presentation). Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/FareezaM/basics-of-chunking/16-Example_Conte…;

Miller, G. (1956). The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information. Psychological Review, 63(2), 81-97.

https://unh.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01USNH_UNH/1o8seis/cdi_proquest_miscellaneous_81667847

Northern Illinois University Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. (2020). Gagne’s nine events of instruction. In Instructional guide for university faculty and teaching assistants. Retrieved from https://www.niu.edu/citl/resources/guides/instructional-guide/gagnes-nine-events-of-instruction.shtml

University at Buffalo Center for Educational Innovation. (2021). Constructivism. Retrieved from http://www.buffalo.edu/ubcei/enhance/learning/constructivism.html

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by Design (Expanded 2nd ed.). Alexandria, Virginia: Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development.

https://unh.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01USNH_UNH/1g6a9m7/alma99…;