Examining the Effectiveness of Video Marketing Based on Consumer Attitudes: Differences between Generation Zers and Baby Boomers

Consumers are surrounded by video content now more than ever. Every day we spend hours watching video content that educates, inspires, and entertains, and this amount of time exploded during the pandemic (Hayes, 2021). People devote one-third of their internet time to watching videos, and it is predicted that by 2022, video will account for 79% of all mobile data traffic and 82% of all internet traffic worldwide (Bowman, 2017; Ofcom, 2019; Khabab, 2020).

The author, Joslyn Villavicencio. (Source: McNair Scholars Program.)

Video marketing refers to the use of videos to support and sell a product or service to maximize interaction on a company’s digital and social platforms, educate its audiences and clients, and reach out to new consumers (Collins & Conley, 2021). Video marketing functions across all aspects of marketing, from raising customer awareness of a company’s products and services to retaining existing customers. Companies need more knowledge of video marketing going forward, because 54% of consumers want to see video content from businesses and brands they support (Collins & Conley, 2021). Additionally, 87% of video marketers report that video has a good return on investment (Hayes, 2022). Video marketing is a powerful marketing tool now, and its influence will continue to increase in our content market.

The rapid growth of video has outpaced research on the topic, and much has not yet been explored. There is currently scarce research on ways to make video marketing effective across different generations. As a result, I opted to pursue my own study, financed by the McNair Scholars Program, to obtain insight into the perspectives of baby boomers (1946–1964) and Generation Zers (1997–2012) on video marketing, as well as to determine the characteristics they find appealing and identify the most effective methods for video marketing to these generations.

The knowledge gained through video marketing research is valuable because it demonstrates which parts of a video make it interesting and enjoyable to watch. This knowledge may also be applied in the school system, so instructional video creators will know what to add in their videos to keep students engaged. Thus, the students will be more attentive and as a result will learn more efficiently.

As a business administration management major with a learning disability, I’m especially interested in this topic because video marketing helps me understand topics better on a daily basis by making information more digestible for me. My research began with a literature review, followed by exploratory research through focus groups, and concluded with a survey of Generation Zers and baby boomers regarding their consumption of video marketing.

Literature Review

My mentor helped me expand my knowledge of video marketing by providing me with research articles that would give me a comprehensive understanding of my research subject. I also explored the UNH database for research papers on video marketing, Generation Zers and baby boomers, and spoke with the UNH business librarian for materials to complete my literature review. When drafting the framework for my literature review, I intended to introduce the reader to video marketing while also easing into the generational aspect of my research topic.

Digital marketing, in the form of websites established by brands and businesses to entice customers, laid the groundwork for video marketing. When marketers determined that pop-up ads were not an effective advertising tool because consumers were using ad blockers, they began to adapt their techniques and turned to more personalized forms of marketing, including the use of videos (Collins & Conley, 2021).

Video marketing attracts consumers to sellers’ products and services through television, social media, and video games. Consumers in this context are described as anybody who consumes content such as watching videos online for leisure, seeing a non-skippable commercial, or making monetary transactions. Consumers and companies work together, because without one, the other would not exist. It is a cycle of consumers wanting content and companies creating content to meet consumers’ wants.

Consumers are more likely to absorb information quickly when it is presented in a visual way (Collins & Conley, 2021). Visual content creates a connection between the consumers and the companies. Watching video content displaying another person’s emotions activates our mirror neurons (Blaschka, 2019). Furthermore, video marketing humanizes a seller when you’re watching a video of the brand you support (Bowman, 2017).

Studies have shown that there is an increase in web traffic for websites and social media if the ads contain videos (Oziemblo, 2020). Video content on Facebook increases website engagement by 33%, and 93% of individual Facebook users watch video content (Costa Sànchez, 2017). Most of the platforms that receive the highest percentage of time spent are platforms that have video content. Generation Zers mostly use social media platforms, where percentages by time spent on a weekly basis were 89% on YouTube, 74% on Instagram, and 68% on Snapchat (Baron, 2019). Valuable video content platforms such as YouTube are becoming an outlet that Generation Zers can use to decompress and feel less stressed about schoolwork or extracurriculars (Baron, 2019).

Mobile phones have increasingly become video oriented, which is opening more consumers to video marketing (Rahal, 2019). Ofcom (2019) reports that 96% of baby boomers aged 55–64 and 92% aged 64–74 use a mobile phone. baby boomers might not spend as much time with technology as Generation Zers, but they use the internet as much as other generations. Facebook is the most popular social media platform used by baby boomers. Like Generation Zers, they also enjoy YouTube; 70% of baby boomers in the United States use this platform (Pitta, 2019).

Nevertheless, research has shown that companies focus most of their attention on Generation Zers and fail to reach baby boomer audiences (Quora, 2019). Digital marketers are often reluctant to focus on baby boomers because of ageism in the marketing industry (Quora, 2019). Companies spend only an estimated 5 to 10% of their marketing dollars to get knowledge about what attracts baby boomers. However, baby boomers have significantly more spending power than Generation X and millennials (Quora, 2019). The assumption that baby boomers don’t like to engage with technology is not true: baby boomers embrace digital life. Baby boomers are also a valuable audience, because if they support a brand, they stay loyal to that brand (Wilson, 2022). Marketers should keep the baby boomer generation in mind while developing marketing strategies.

To better understand the effectiveness of video marketing, research needs to focus on both the older and the younger generations so that companies can understand the differing needs of their consumers. It is important for companies to know what attracts these different types of audiences to these platforms. Therefore, the next phase of my research focused on two questions: (1) What are the characteristics of video content that engages these audiences, and which are most important for consumers’ decision making? and (2) How do these characteristics vary between baby boomers and Generation Zers?

Methodology

After conducting my literature review, I held two focus groups, one with Generation Zers and another one with baby boomers. I recruited participants through social media and word of mouth. Each focus group was conducted on Zoom and consisted of five people, and the discussion lasted for thirty minutes. Participants were asked thirteen questions that my mentor and I developed, including items such as, “What qualities do you enjoy in a video? What length video do you consider to be short or long? What qualities do you like and hate in a video?” I led the discussion of the focus groups, and recorded and transcribed the replies into a document. I used the findings from these discussion groups to help develop the questions for the next part of my research, the survey, ensuring that the items and vernacular would be consistent and understood across both groups.

I then created a five-question, multi-item survey in Qualtrics to collect information on individuals’ perceptions of video marketing. The survey followed the protocols of the sponsoring University of New Hampshire (UNH) and was approved by its Institutional Review Board (IRB). This survey was conducted using separate samples of Generation Zers and baby boomers, not those who had participated in the focus groups. Participants were recruited through Prolific, an online research panel company that assists researchers in finding participants for internet studies by providing renumeration to panelists who take surveys. Panels such as Prolific or Amazon MTurk are commonly used to obtain survey responses from consumers (Aguinis et al., 2021). Moreover, because the topic being examined is online video consumption, the use of online panelists assures that respondents are familiar with video marketing.

With Prolific I was able to set criteria for the participants I needed to take my survey. If a participant met the requirements, the study was added to their participant page. The participants then had to complete the survey and submit it through Prolific. Prolific provided me with data from the participant responses that was easily exported to Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), which I used for data analysis. The final sample was 101 Generation Zers and 98 baby boomers.

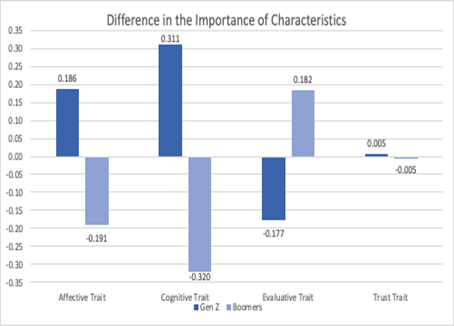

Figure 1: This figure shows significant contrasts between Gen Z and baby boomer generations in terms of the importance they place on four characteristics of videos: evaluative, affective, cognitive, and trust. The average level of importance is 0; the more positive the score, the more important it is; the more negative the score, the less important it is. For example, cognitive ability is extremely significant to Generation Zers but not to baby boomers.

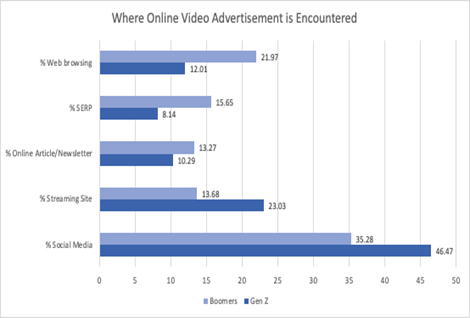

Figure 2: This graph shows where baby boomers and Gen Z encounter video advertisements as expressed by average percentages from their responses. Both groups encounter videos mostly through social media. Baby boomers encounter more videos through web browsing than Gen Z, who in contrast rely more on streaming sites. SERP = Search Engine Response Page.

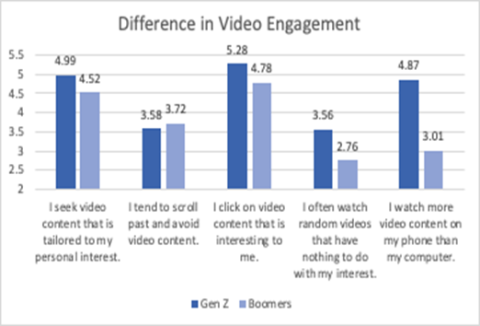

Figure 3: Bars indicate the average (mean) level of engagement of each group on a scale of 1-6. Higher scores indicate they engage more with video in that way. There is no significant difference across generations when it comes to scrolling past videos. However, there is a significant difference for all other questions.

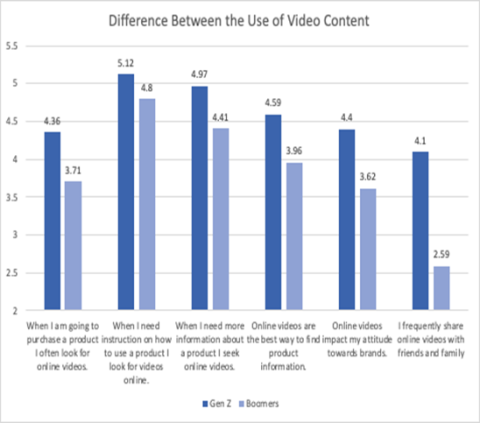

Figure 4: Bars indicate the average (mean) level of video usage for each group on a scale of 1-6. Higher scores indicate higher use of video in that particular way. Significant differences can be seen in all types of use.

Analysis

The data set was initially analyzed using descriptive statistics to understand the differences in responses between Gen Z and baby boomers. This was followed by exploratory factor analysis using SPSS of the thirteen items in Question 1 (see appendix for the complete list of questionnaire items). Exploratory factor analysis is used to find the underlying components from a large group of survey items by condensing their data into a smaller, more manageable group of common factors. Further comparison of Gen Z and baby boomer responses followed the factor analysis.

The first question set in the survey was “When judging video content online, such as on a website or social media (i.e., Instagram, YouTube), how important are the following attributes?”

Respondents were asked to rate thirteen items on a scale of 1 to 6, with 1 being not at all important and 6 extremely important. Examples of these attributes were the quality of video, production, and entertainment value. Based on the exploratory factor analysis, the items were categorized under four separate factors named evaluative (videos with attributes that are worth the time to watch); affective (videos with attributes that create emotional impact); cognitive (videos with attributes that provide good quality content); and trust (videos with attributes that demonstrate credibility of the source). The exploratory factor analysis provided the factor scores as new variables for each respondent. We then compared the means of the factor scores of Generation Zers and baby boomers. We found that

Generation Zers are drawn to affective and cognitive videos, whereas baby boomers are drawn to

evaluative videos. Both generations felt the same about trust videos. These differences are shown in Figure 1.

Question 2 of the survey sought to examine where participants view their video advertisements and determine if there is a difference between baby boomers and Generation Zers. Examples of where they encountered video advertising included social media, streaming sites, and search engine response pages, among others. (See the appendix for a complete list.) The results show that baby boomers are more web oriented, whereas members of Generation Zers are more social media oriented. This is shown in Figure 2.

Question 3 probed the value of several specific features such as playback speed, subtitles, and the ability to skip forward or backward five seconds on a video, which is known as the five-second skips button. Participants could rate their value of these features on a six-point scale. As a result of the examination of this question, we find that Generation Zers values videos with all five of these features more than baby boomers do.

Question 4 asked about how viewers engage with video material. One of the goals of this study was to see how the general attitudes and habits toward video content influenced whether a participant would view a video. We asked their tendencies to seek out video content or scroll past it, and what device they used to interact with the video. As shown in Figure 3, overall, the results show more engagement with video content by Generation Zers than baby boomers, although the differences were not large. We found no difference between tending to scroll past videos and avoiding video content between generations. Question 4 also asked if participants typically click on video content that interests them, if they often watch videos at random, and if they watch video content on their phone or computer. The results show that both groups are similar in the ways that they engage with video content except that Generation Zers tends to watch more videos at random than baby boomers, and Generation Zers watches video content on their phones, whereas baby boomers use laptops.

In the final question set we examined the use of product-related video content and found striking differences between Generation Zers and baby boomers. The results showed that in every case, Generation Zers interacts with video content more than baby boomers, particularly when seeking information when considering a product purchase. This is shown in Figure 4. “When I need instruction on how to use a product, I look for videos online” was the item rated the highest by both groups and also showed the smallest difference between groups. We discovered that Generation Zers uses video content to learn about products, that it impacts their attitudes toward a product, and that they share video content more than baby boomers do.

Summary

In conclusion Generation Zers and baby boomers differ on certain characteristics of what makes video content effective. Many characteristics need to be considered, as both generations consume video differently. I discovered that affective and cognitive videos appeal to Generation Zers, whereas evaluative videos appeal to baby boomers. Neither generation placed great importance on trusting the credibility of the source. Baby boomers are more interested in the web-oriented content, and Generation Zers are more interested in content through social media. Generation Zers value playback features in video more than baby boomers. Findings demonstrate that both generations engage with video material in comparable ways, with the exception that Generation Zers view more videos at random than baby boomers, and Generation Zers consume video content on mobile phones, whereas baby boomers watch it on computers. It was also noticeable that Generation Zers utilize video material to learn about products, distribute video information, and learn about customer views regarding a product more than baby boomers, but baby boomers seek out information on how to use a product almost as much as Generation Zers.

As a result, we can see how different both generations’ video preferences are, which helps us learn more about video marketing. These differences suggest that video content producers may focus more on different attributes, depending on the target audience of their videos. However, it would be a mistake to conclude that the stronger engagement by Generation Zers indicates that video content for baby boomers is not valuable. Although the engagement and use is not as strong, baby boomers clearly use video content, and it can be fashioned to meet the needs and appeal to this group as well as to Generation Zers.

Personal Reflection

This research has led me down a path that I never imagined would take me this far. I told my father that I was going to be a published author while I was in the final draft of my research paper, and it seemed awkward to say it, but I know he is proud of me for publishing this article in Inquiry. I’m also proud of myself for the confidence I gained through this research and writing process. In addition, I’ve had the opportunity to present my findings in different states in the United States, which has been an experience I never dreamed of when I submitted my research proposal. With the commencement of this research study, my future became clearer and helped direct me to my next steps for the future, which is to pursue a master’s degree, or perhaps go further and pursue a PhD. The research life has gradually grown on me, and I hope that whichever career path I select, I will be able to make a difference.

I want to express my gratitude to Dr. Billur Akdeniz Talay, who helped me with my research proposal, and Dr. Thomas Gruen, who mentored me through this research and writing experience. I would also like to thank my McNair advisers, Selina Choate and Tammy J. Gewehr, for guiding me through this journey and advising me on the best course of action. I want to thank my McNair cohort for making this journey enjoyable. I would also like to thank everyone who helped me revise my paper. I know I have a lot of trouble writing, so having someone review my research and make sure I presented my research correctly was appreciated. Last but not least, I want to thank my parents for always seeing the best in me and supporting my education.

Appendix

1. When judging video content online, such as on a website or social media (i.e. Instagram, YouTube), how important are the following attributes to you?

(6 point scale)

<et>

- Quality of the video

- Production

- Entertainment Value

- Customization of

- Video such as custom

- Speed, playback, and

- Subtitles

- Trust that the content

- Is credible

- It uses storytelling

- Moves me emotionally

- Short and sweet video

- Thumbnail and title

2. Approximately what percent from each other of the following do you encounter online video advertising? (Total should equal 100%)

<open-text field with validation that ensures entries are percentages>

- Social media

- Online article/Newsletter

- Search engine response page

- Web browsing

- Streaming Site

- Other, describe

3. How valuable is each feature to you when watching video content? Indicate by selecting a point along the scale?

(6 point scale)

<Not at all valuable -Extremely valuable>

- Playback speed (option to make video slower or faster)

- Subtitles (ability to turn on and off)

- 5-second skips

- Option to select video quality (higher or lower resolution

- To have the ability to skip directly to a specific section

4. Please indicate to what extent you agree with the following statements:

(6 point scale)

<Strongly disagree - Strongly agree>

- I seek video content that is tailored to my personal interest

- I tend to scroll past and avoid video content

- I click on video content that are interesting to me

- I often watch a random videos that have nothing to do with my interest

- I watch more video content on my phone than my computer

5. Indicate the level you agree or disagree with the following statements:

(6 point scale)

<Strongly disagree - Strongly agree>

- When I am going to purchase a product I often look for online videos

- When I need instruction on how to use a product I look for videos online

- When I need more information about a product I seek online videos

- Online videos are the best way to find product information

- Online videos impact my attitudes towards brands

- I frequently share online videos with friends and family

References

Aguinis, H., Villamor, I., & Ramani, R. S. (2021). MTurk Research: Review and Recommendations. Journal of Management, 47(4), 823–837. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206320969787

Alicia Collins and Megan Conley. (2021, May 19). The Ultimate Guide to Video Marketing. HubSpot Blog | Marketing, Sales, Agency, and Customer Success Content; HubSpot. https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/video-marketing

Baron, J. (2019, July 3). The Key To Gen Z Is Video Content. Forbes; Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/jessicabaron/2019/07/03/the-key-to-gen-z-is...

Blaschka, A. (2019, July 12). Science Says To Do This One Thing To Produce The Biggest Results. Forbes; Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/amyblaschka/2019/07/12/science-says-to-do-t...

Bowman, M. (2017, February 3). Video Marketing: The Future Of Content Marketing. Forbes; Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2017/02/03/video-market...

Costa Sànchez, C. (2017). Online video marketing strategies: typology according to business sectors. Communication & Society, 1. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.30.1.17-38

Hayes, A. (2022, January 26). What Video Marketers Should Know in 2022, According to Wyzowl Research. HubSpot Blog | Marketing, Sales, Agency, and Customer Success Content; HubSpot. https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/state-of-video-marketing-new-data

Khabab, O. (2020, July 3). 2020 Video Marketing Trends And Predictions. Forbes; Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2020/07/03/2020-video-m...

Ofcom. (2019a, May 30). Adult Media Use and Attitudes Report 2019. Ofcom.Org.Uk; Ofcom. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0021/149124/adults-media...

Oziemblo, A. (2020, January 7). The Evolution Of Digital Marketing To Video Marketing. Forbes; Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2020/01/07/the-evolutio...

Pitta, Jeff, and Young Entrepreneur Council. (2019b, November 7). 4 Ways to Reach the Senior Audience in 2020 | Inc.com. Inc.Com; Inc. https://www.inc.com/young-entrepreneur-council/4-ways-to-reach-senior-au...

Quora. (2019, November 15). Why Are So Many Companies Ignoring The Baby Boomer Market? Forbes; Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/quora/2019/11/15/why-are-so-many-companies-...

Rahal, A. (2019, December 19). Why Marketers Should Integrate Video Marketing Into Their Content Strategy. Forbes; Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescommunicationscouncil/2019/12/19/why-...

Wilson, L. (2022, March 16). 6 Ways To Target Seniors More Effectively In Digital Marketing. Search Engine Journal; SearchEngineJournal. https://www.searchenginejournal.com/digital-marketing-to-seniors/312545/#close

Author and Mentor Bios

Joslyn Villavicencio, a junior from Nashua, New Hampshire, is pursuing a bachelor of science degree in business administration: management at the University of New Hampshire. She is a member of both the TRIO Scholars Program and the McNair Scholars Program, the latter of which funded her research on effective video marketing to Generation Zers and baby boomers. She found that she concluded her work with more questions than answers, but attributes this to being part of the scientific process. The most difficult aspect of conducting research during the pandemic was juggling a lot of responsibilities: caring for her two younger siblings during the day and completing schoolwork and research at night. Joslyn said that this research experience increased her confidence and helped her realize that she wants to obtain a master’s degree in business administration. Joslyn chose to submit to Inquiry because of the opportunity it provided to publicize her work.

Thomas W. Gruen has been a professor of marketing in the Peter T. Paul College of Business and Economics at the University of New Hampshire since August 2011. His research specialization is relationship marketing, which is a strategy of customer relationship management that focuses on long-term satisfaction and brand loyalty. In addition to teaching, he serves as the faculty advisor for the Voice Z Digital agency, a student-run digital marketing agency. When Dr. Gruen became involved with Joslyn Villavicencio’s project, he had recently stepped down from serving nine years as the marketing department chair. This provided him with the time he needed to devote to a student and project of this extent. He previously supervised independent studies and honors theses, but Joslyn’s research marked his first time working with the McNair Scholars Program. Dr. Gruen encourages more Paul College students to write for Inquiry to gain experience taking their research from a poster presentation to a published article. He explains that this process requires significant elaboration and revision, but it’s worth it to see your work in print.

Copyright 2022, Joslyn Villavicencio