Effects of COVID-19 on Food Insecurity within New Hampshire and the UNH Community

The COVID-19 pandemic has created socioeconomic distress for individuals across the globe, including changes in employment status, income, and access to childcare. With additional financial hardship, the rate of individuals struggling with food security has increased. Feeding America projected a national food insecurity rate of 12.9% in 2021, which is up from 10.5% in 2019 (Feeding America, 2021). Food insecurity refers to the disruption of reliable food intake or eating patterns due to the lack of money and other resources. Increasing rates of food insecurity impact the entire community and lead to declines in nutritious diets, mental health, and academic performance. Educational outreach efforts, important resources specifically for those in low-income communities at the highest risk of food insecurity, were significantly affected by the pandemic. As a nutritional sciences major at the University of New Hampshire (UNH), I was inspired by these factors to conduct research on how food insecurity has affected the residents of New Hampshire, including the local UNH Durham community.

The author, Sarah Waleryszak

With almost 20 million Americans attending college in 2020, many young people may be at risk for food insecurity (National Center for Education Statistics, n.d.). Young adulthood (ages 18–26 years old) is an important time for developing a healthy lifestyle; however, many college students experience declines in healthy behaviors (Nelson et al., 2012). Increasing rates of food insecurity among college students have been linked to the increase in tuition rates and number of low-income college students as well as insufficient financial aid. Additionally, college students are excluded from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), unless they meet specific student exemptions, including working a paid position for at least 20 hours a week (Freudenberg et al., 2019). This puts them at a further disadvantage when trying to find ways to enhance their food budget.

A 2016 multistate study conducted across more than 30 campuses found 47% of four-year students and 50% of community college students had experienced food insecurity within the previous 30 days (Dubick et al., 2016). These rates are alarmingly high and show the presence of extreme financial stress among students across the country. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused additional stress on college students, leading to more financial hardship and delays in graduation. Further, those of a low-income background were 55% more likely to have to delay graduation than their higher-income peers (Aucejo et al., 2020). These effects of food insecurity on college enrollment prompted my investigation, which was supported by the Hamel Center for Undergraduate Research’s Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF).

In summer 2021, fellow undergraduate student Laura Lynch and I conducted two studies to understand the influential factors surrounding food security in New Hampshire at the state level as well as locally in the UNHD community. We conducted two separate focus groups to understand the challenges people faced relating to food security during the Covid-19 pandemic: one with NH Cooperative Extension educators and another with undergraduate students. By exploring the reasons for local food insecurity, my goal was to increase awareness and contribute to the development of effective and appropriate outreach techniques for food assistance programs.

New Hampshire Statewide Study

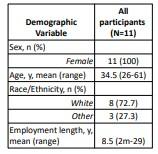

Figure 1: Demographic information of Cooperative Extension educators.

Participants in the first study were members of the UNH Cooperative Extension who work to educate individuals within their counties on topics surrounding economics, cultural activities, and assistance programs. With guidance from Amy Hollar, healthy living state specialist from UNH Cooperative Extension, we recruited 11 participants who completed a self-reported demographic and food security questionnaire. (See figure 1.) Participants (100% female, 73% white) were asked to complete the survey based on their NH Cooperative Extension territory, rather than their home community. The participants’ average length of time working with Cooperative Extension was 8.5 years, giving a good background for comparing their experience with community members prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

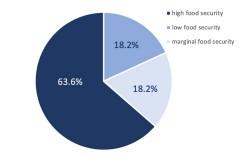

This US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Two-Item Food Security Screening Tool, which is derived from questions two and three of the U.S. Adult Food Security Survey Module, asked participants to respond “definitely no,” “mostly no,” “mostly yes,” or “definitely yes” to two statements: “In the last year, I worried about whether my food would run out before I got money to buy more,” and “In the last year, the food I bought just didn’t last and I didn’t have money to get more” (US Department of Agriculture, 2012). Based on their responses, a scaling chart was used to determine that 18.2% of the community had low food security.

Figure 2: Rates of food security within the NH counties the Cooperative Extension educators serve.

Two separate focus groups, one led by me and a second led by Lynch, each with five or six Cooperative Extension staff, were then conducted on Zoom. We asked the participants to respond according to the information they had received while working with their community members. Through these open discussions, a number of themes were uncovered by recording and analyzing the meeting transcripts using Nvivo, a transcription service, and Delve, an online program that allows the user to flag keywords and phrases in order to uncover the common themes of a discussion.

First, we discovered that the cost and overall finances associated with groceries and creating healthy, balanced meals was a challenge for many individuals even before the pandemic. COVID-19 made this harder on families, as many had to balance work with at-home childcare, making it difficult to find time to create healthy meals while also dealing with the increased prices of many goods.

Second, accessibility was a large area of concern, especially for those in low-income communities and/or those in rural communities. During the pandemic, many food pantries had to close or find alternative ways to make food available to clients, such as mobile food pantries. Through these pantries, the options were limited due to insufficient donations and grocery store shortages of a variety of items. Therefore, individuals were not always able to select the food they would like.

FIgure 3: The common these that arose from our discussion with Cooperative Extension Educators during the focus groups.

As one participant said, “We were not really eating vegetables or fruits or fresh produce very much. We were getting whatever we were getting from the mobile pantry.” Many soup kitchens and community dinners, which had served as a stable resource for many individuals before the pandemic, were also shut down due to social distancing. Additionally, residents could not meet with Cooperative Extension staff in person to discuss options for assistance programs.

Although there was a lack of communication at the beginning of the pandemic, one particularly helpful resource that arose was the use of Zoom or other video call services. It provided individuals with the flexibility to have meetings and other appointments from home. This was especially helpful for those with limited access to transportation or who were living in rural areas where they would have to drive far distances to access their doctor or meet with educators. Therefore, this resource helped families save money by decreasing the amount of needed childcare and transportation while allowing them to have more money for food.

University of New Hampshire Study

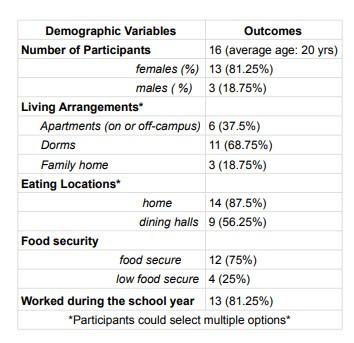

Figure 4: Demographic information of participants from the UNH study.

Our second study focused on food insecurity on the UNHD campus and the factors that contributed to this during the COVID-19 pandemic. Data for the UNH project were collected from 16 undergraduate students (mean age of 20 years). Students were recruited by distributing emails to students in university clubs and those partaking in summer classes. I created a self-reported demographic questionnaire through Qualtrics and distributed it through email. The survey included the USDA six-item food insecurity questionnaire, which asks six questions related to eating habits and food access within the individual’s household to determine their level of food security (US Department of Agriculture, 2012).

Lynch and I then conducted five separate focus groups via Zoom with two to five participants in each group to collect qualitative and quantitative data related to food insecurity. During these one-hour meetings, we discussed the effects of COVID-19 on the culture and resources available on the UNH campus and in the Durham community. I prompted questions throughout the meeting to guide the discussion while Lynch took notes on the topics being discussed. Participants were asked to answer only when they felt comfortable, as food insecurity can be a difficult topic for some individuals.

Most participants were female and living either in an apartment or in an on-campus dorm. A large majority reported working during the school year, and 37.5% reported that their economic status was negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Although most participants reported living in on-campus dorms where purchasing a dining plan is required, many of them reported preparing and eating their meals at their on-campus residence more often than in the dining halls. The USDA six-item food insecurity questionnaire ranks the responses to each question and is used to determine the level of food security among respondents. Question responses of “often,” “sometimes,” “almost every month,” and “some months but not every month” were coded as “yes.” Those with 0–1 “yes” responses are determined as being high or moderately food secure, 2–4 are low food secure, and those with a score of 5–6 are very low food secure. Of the 16 participants, 25% were determined to have low food security, while the other 75% reported being food secure.

Figure 5: Common themes that arose during the focus groups with UNH Students. They expressed barriers within the community, health, and food related-areas.

Each meeting was recorded and then each transcript was analyzed using the online software program Delve to find common themes. The themes that emerged included a lack of knowledge of available resources pertaining to food assistance, concerns pertaining to the dining hall, and an overall increase in stress and anxiety. Multiple participants noted a lack of a central location, such as a website, for all wellness-related resources on campus. A platform like this could also offer additional information related to food insecurity, such as resources for mental health and eating disorders.

Additionally, participants discussed how COVID-19 decreased dining hall accessibility due to social distancing and the fact that dining hall staff had to serve all the food instead of students being able to help themselves. They cited a (perception of the) lack of healthy options and variety, presumably due to the need for prepackaged and easily served foods that are liked by a majority of students. One participant said, “I spent more of my own money during the school year trying to get food out, like outside the dining hall, because the choices were just really lacking a lot of the time.”

Participants also shared concerns surrounding options for those with food allergies. One participant said, “Some of my friends on campus who had dietary restrictions said they had a hard time finding stuff in the dining hall that was good for them.” Participants also noted that before the pandemic, there seemed to be more dining hall staff to ensure no cross-contamination occurred and that all items were properly labeled. Dining hall selection, especially for those seeking healthy meal options or allergy-friendly options, was a large area of concern for the participants.

Figure 6: Recommendations from students for how to improve food security and ability to live a healthy lifestyle on campus. “PACS” stands for UNH’s Psychological and Counseling Service.

Individuals also discussed how the dining hall became an additional place of stress during the Covid pandemic. One participant said, “People who have eating disorders had a really hard time in the dining halls this year because it was served by the dining hall workers and [people] had little control [over] how much of an item they were being served.” A second participant added, “I think a lot of people also get a lot of anxiety going to the dining halls.” Especially since everyone was encouraged to social distance and keep a small circle of friends, participants expressed a decrease in the number of meals students were eating each day, “because they don’t want to go to the dining hall alone or because they have anxiety eating in front of people.”

As seen, these students showed concern for many important topics. They identified access to wellness resources, allergy-friendly food availability, and dining-hall-related anxiety and stress as the primary topics of concern. Because this study contained only a small cohort of students, additional data will be needed to draw conclusions; however, this information is beneficial to identify the barriers faced by students and allows for the design of more appropriate and effective programs surrounding food access on the UNHD campus.

Conclusion

These studies are part of a larger project my mentor is involved with that is funded by the USDA and New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station titled “Understanding and Promoting Health and Nutrition in Communities of Emerging Adults.” It is a five-year project focused on the impact of environmental, behavioral, and disruptive factors on weight-related conditions among young adults. The studies we completed for SURF focused on the second and third objectives of the larger project: Objective 2: “Development of policy, systems, environment (PSE) assessment tools for urban and rural communities with low income considering social determinants of health and influential disruptive factors (IDFs)”; and Objective 3: “Expanded understanding of college students’ dietary patterns considering social determinants of health and influential disruptive factors (IDFs) with an emphasis on food security, mental health, and the built environment.”

Overall, we hope this research will increase awareness of food insecurity and findings can be used to contribute to the development of appropriate and effective food assistance programs both on campus and statewide. Results from these studies denote the need for a central location of resources online, both for UNH and New Hampshire as a whole. Additionally, New Hampshire is one of the only states that does not have a SNAP outreach coordinator, an individual who works to promote and assist with application and enrollment as well as coordinate outreach efforts for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. By adding this position, individuals would have increased support in understanding how to utilize this important program to increase their food security.

Through my analysis of demographic and focus group data, I was able to apply knowledge from the classroom to the critical issue of food insecurity. I gained multiple professional skills and had the opportunity to learn from experts in the field of research and nutrition. This experience showed me how important research is for bettering the lives of those within our local and greater communities and motivated me to conduct clinical research after becoming a physician assistant.

First, I would like to thank Dr. Jesse Stabile Morrell for guiding me through the process of applying and conducting this research. She has had a major influence on my experience at UNH, providing a wealth of knowledge related to the field of nutrition research. Next, I would like to thank my fellow student Laura Lynch for assisting in the conducting of focus groups and transcript analysis. I am also grateful for those who participated in the focus groups. Without their insight, this project would not have been possible. Additionally, I would like to thank my family and friends for their encouragement and support through the research process. Lastly, I appreciate the generosity of the Hamel Center for Undergraduate Research, especially the donors who funded my research: Mr. Dana Hamel, the Dorothy Perkins O’Neil Endowed Fund, and Ms. Anne Sarkisian.

References

Aucejo, E. M., French, J., Paola Ugalde Araya M., Zafar, B.. (2020, November). The impact of COVID-19 on student experiences and expectations: Evidence from a survey. Science Direct, Journal of Public Economics. doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104271

Dubick, J., Matthews, B., Cady, C. (2016, October). Hunger on campus: The challenge of food insecurity for college students. University of California. https://studentsagainsthunger.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Hunger_On_C...

Feeding America. (2021, March). The impact of the coronavirus on local food insecurity. https://www.feedingamerica.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/Local%20Proje...

Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2021, October 1). SNAP eligibility. Retrieved March 24, 2022, from https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/recipient/eligibility

Freudenberg, N., Goldrick-Rab, S., & Poppendieck, J. (2019, November). College students and SNAP: The new face of food insecurity in the United States. American Journal of Public Health.

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) (n.d.). Retrieved April 6, 2022 from https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=372#College_enrollment

Nelson, M. C., Larson, N. I., Lytle, L. A., Neumark-Sztainer, D., Story, M. (2012, September). Emerging adulthood and college-aged youth: An overlooked age for weight-related behavior change. National Library of Medicine. doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.365

U.S Department of Agriculture. (2012, September). U.S. Adult Food Security Survey Module - USDA ERS. Retrieved from https://www.ers.usda.gov/media/8279/ad2012.pdf

US Department of Agriculture. (2012, September). U.S. household food security survey module: Six-item short form. https://www.ers.usda.gov/media/8282/short2012.pdf

Author and Mentor Bios

Sarah Elizabeth Waleryszak, from Newmarket, New Hampshire, is a nutritional sciences major who will graduate in May 2023. Besides conducting her own research, Sarah also serves as a research assistant for the College Health and Nutrition Assessment Survey (CHANAS). During spring 2021, Sarah began researching the difference in rates of food insecurity prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sarah specifically wanted to investigate the barriers students faced with campus resources and food security. She said that the overall research process went smoothly, including learning how to apply for a research grant, obtaining Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, transcribing data from focus groups, and finally publishing her research. Sarah decided to submit to Inquiry because it gave her an opportunity to educate and share her findings with a greater audience, while also discussing areas of improvement for addressing food insecurity in our community. With her research Sarah hopes she will be able to bring a new perspective to the way we assist those who are experiencing food insecurity. After graduation Sarah hopes to continue her education to become a physician assistant and conduct clinical research.

Jesse Stabile Morrell is a principal lecturer for the nutrition program in the Department of Agriculture, Nutrition, and Food Systems at the University of New Hampshire, where she has taught since 2001. Specializing in human nutrition and nutrition education, Dr. Morrell has been part of the USDA-funded multistate collaborative Healthy Campus Research Consortium since 2009, when she first became involved as a Ph.D. student. The consortium aims to “support campuses and other communities in creating environments and opportunities that embrace young adults’ unique barriers to a healthy lifestyle, promote healthier weights, and reduce health disparities among vulnerable members.” It was for this reason that she became involved with Sarah Waleryszak’s project on food insecurity, which, she notes, is a fundamental concern for all communities. Dr. Morrell was extremely satisfied with the independence that Sarah showed during her research. She believes that Inquiry provides a valuable opportunity for students to think critically about communicating their scientific research to the public. “As our society grapples with misinformation/disinformation, scientists in all fields need to improve their communication skills if we hope to have a positive impact,” Dr. Morrell says.

Copyright 2022, Sarah Elizabeth Waleryszak