Understanding the Influence of Space on Participation within Mental Health Care and the Surrounding Community

In the last decade, dialogue about mental health has steadily been increasing. As discussion on this once-taboo subject becomes more mainstream, it is important to recognize and understand current treatment options and their efficacy. Research in this arena will ensure those who seek mental health services can receive the most effective, research-based treatment available.

The subpopulation of those with serious mental illness (SMI) are those receiving many of these different treatment services. SMI is better described as a specific subset of mental illness that results in serious functional impairment that interferes with daily life activities. Diagnoses such as major depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder are common examples of SMI. In 2020 there were about 14.2 million individuals in the United States living with SMI (NIMH, 2022). The onset for these diagnoses typically starts among young people aged eighteen to twenty-five, and the prevalence decreases as age continues to rise (NIMH, 2022). Research into the effective treatment of SMI is necessary to identify the social mechanisms connecting space, stigma, belonging, and community participation for this historically marginalized population.

Throughout the summer of 2023 I conducted a mixed-methods research project with a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) from the Hamel Center for Undergraduate Research. My exploratory project aimed to collect preliminary evidence on participation in community mental health services. I was introduced to this research area by my mentor, Professor Nikhil Tomar, who conducts research within the domain of mental health, and I soon became interested in spearheading my own project. My research site in New Hampshire was a clubhouse, which is a community-based psychosocial rehabilitation facility, and my research began after completing a semester-long volunteer experience at the same location for a previous class. Following this experience, I was curious about how the space in and around this rehabilitation program affects the participation of its members. In this context, space is defined as the physical and social/cultural aspects of an environment that is used to facilitate rehabilitation. I analyzed the impact of space on community participation and engagement at a clubhouse, looking at the space within the facility and the surrounding area.

Community-based Treatment and Rehabilitation

A clubhouse uses a specific model of psychosocial rehabilitation in the form of a community mental health service that helps people with a history of serious mental illness. The clubhouse model uses a nonclinical setting, open to anyone who has a history of mental illness and has been referred by a provider. These individuals are referred to as members in the clubhouse.

The clubhouse model is run on a day program, typically following a 9 a.m.–5 p.m. schedule, during which the members perform different tasks and have responsibilities. This schedule helps members engage in meaningful work at the clubhouse during typical workday hours. It is important to note that the usual provider/patient relationship does not exist; instead, a collaborative approach is used to promote rehabilitation.

Treatment and rehabilitation provided through the community and its support, as opposed to the traditional medical or hospital setting, is an emerging practice area that has been scientifically explored by researchers. However, it continues to experience policy and social challenges because of its nontraditional care paradigm. Therefore, this research area, compared with the more prominent areas of research in occupational therapy on assessments and the efficacy of treatment plans, fills this critical gap by studying the space where treatment takes place, through lived experiences and voices of people living with serious mental illness. Increased research in this area will also better promote the effectiveness of occupational therapists within community mental health services, which is an emerging domain.

Community Mental Health and Stigma

Having a deeper understanding of the history of treatment for individuals with SMI and how the clubhouse model came to be is integral to understanding its importance and why this area requires more research. The SMI community is a historically stigmatized/marginalized population. Thus, places and strategies of care for this population of people have dramatically changed over the years. Starting in the early nineteenth century, mental hospitals for “insane persons” were common, but the priority on institutionalization diminished after World War II as medical associations began to believe there were more effective treatment alternatives (Grob, 1994), especially given the horrendous conditions under which treatment was provided in asylums. This change in view was reflected in legislation with the Mental Health Care Act of 1946 (Hamm, 2020) and the establishment of the National Institute of Mental Health in 1949 (Grob, 1994).

Despite the considerable push to move away from institutional treatment and care, such as via the Community Mental Healthcare Act of 1963, the transition was not smooth. Health care challenges for both individuals with SMI and their service providers persist to this day, which some psychosocial models, like the clubhouse, try to address.

In the twenty-first century, a common place for community mental health is within a clubhouse. The clubhouse model was founded in 1943 in New York and has slowly expanded to over 350 locations worldwide. The model is used to support and maintain rehabilitation for people living with SMI. Unlike other clinical or psychosocial models, members within this nonclinical rehabilitation setting and staff share responsibility for operating the clubhouse, eliminating the divide between the clinician and patient roles. Having an equitable relationship with staff is seen as integral for recovery because of its balance and the importance placed on human value and agency (Tanaka et al., 2015). Through a “work-ordered day” members complete both individual and clubhouse tasks and responsibilities alongside each other. These tasks are split into three units. The kitchen unit is responsible for grocery shopping and cooking the daily lunch. The membership unit focuses on attendance, member outreach, and the newsletter. Finally, the business unit focuses on fundraising efforts and daily budgeting. During my fieldwork, I participated in all these tasks alongside members.

The work-mediated interactions allow members to become close, creating community bonds (Tanaka et al., 2021). These positive relationships can help with recovery. Creating personal relationships, while focusing on individual needs, allows members to build a sense of community with each other (Chen, 2017).

Outside the clubhouse, members feel connected to a community and have a sense of belonging through community participation. Feeling connected in your community is linked to many positive outcomes. For example, having high levels of perceived community belonging can lead to lower levels of psychological stress (Terry et al., 2019). However, people living with SMI are typically preoccupied with managing their illness as their major occupation (Andonian, 2010). One reason for this is the lack of focus on community participation within health care structures and policies. Further, the stigma of mental illness also plays a significant role. Perceived stigma around SMI negatively affects individuals’ ability to participate (Gonzales et al., 2018). In addition to perceived stigma, internalized stigma (that is, internalization of prejudiced notions within people with SMI) also acts as a significant barrier to participation.

Partly because of stigma within policies, defined as structural stigma, individuals with SMI live in neighborhoods with higher levels of physical and structural inadequacy, crime, and drug-related activities (Bryne et al., 2013). These neighborhoods with a greater socioeconomic disadvantage are more likely to report perpetuated stigma (Gonzales et al., 2018). Therefore, whether someone is experiencing internal or perceived stigma, its effect is difficult to address. Because of these factors, when such individuals create relationships in the community, their social networks are much smaller compared with people without mental health issues (Dorer et al., 2009). While research about stigma and community participation continues to grow, there is scarce evidence regarding how space is perceived and facilitates or hinders community participation for this historically marginalized population.

Methods

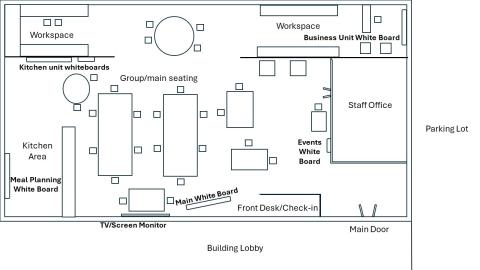

Clubhouse sketched map of internal layout (source: author's drawing).

To address this research gap, I explored through the participants’ own voices how the space within and outside the clubhouse hinders and facilitates community participation for individuals with SMI. By volunteering at this clubhouse before starting research, I had created a positive rapport and friendly relationships with its members. Daily there were typically seven to ten members present with a 1:5 staff-to-member ratio. This trust and familiarity was helpful in my participant recruitment and in my ability to create a safe and comfortable environment for anyone who wished to participate.

For the qualitative methodology, I conducted semi-structured interviews, because they allowed for probing questions and provided participants the opportunity to share perspectives that are important but only remotely connected to the research question. For quantitative methodology, I conducted a survey using the Community Participation Domains Measure (CPDM). The scale measures individual community participation, divided into three major factors: productive activities, social participation, and recreation and leisure. This twenty-five-item scale allows for both subjective and objective answers from participants. The tool allowed for a broader understanding of the participants’ participation within the community and was used to provide context during my analysis of the interviews, as well as to allow the participants to think about their participation before the interview.

I collected quantitative data from participants at two different times starting in July, with the second data collection six to eight weeks later. This was done to minimize the effect of confounding variables, such as participation concerns during a specific period of time in the life of a participant, and the time of year. The time frame between data collections was chosen because of the time constraints of the research project. The use of these tools together provided a more holistic view of the participants’ community participation and how they view what is important and meaningful to them in their surrounding space.

I also conducted observations in the clubhouse two to three times a week over the course of two months. During this time, I completed surveys and interviews in addition to participating and supporting members in the daily clubhouse work-ordered day. Some of these activities were inputting attendance, writing newsletter articles, and preparing daily lunches. Through this process, I fully immersed myself in the culture of the site, understanding all the ins and outs, and building rapport with participants.

I then conducted thematic analysis on the collected data, which was stored in the form of interview transcripts in a Word document. I used the CPDM survey and observational notes to provide context throughout the analysis process, which followed a six-phase approach outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006). The first step was to become familiar with the data, through active, repeated readings of the interview transcripts where I had begun to make notes and highlight sections where participants shared similar experiences. The second step was to generate initial codes by recognizing patterns in data. These were short phrases, sentences, or paragraphs within the transcripts, created by systematically analyzing the data set. Each code identifies a specific feature of the data within a relevant context. For example, this member quote was chosen as a code because of the prevalence of this sentiment within other interviews: “They really support us, and they seem to respect what we do here, what this place is all about, what it provides for people. So it’s positive. Definitely.” Using a side-by-side comparison of the survey results and the interview transcript allowed me to see deeper context in the interview answers.

The third step was to establish themes. I sorted the previously created codes into potential overarching themes that were present among the codes pulled from each of the transcripts. The use of visual representations, such as mind maps, was integral in this step. I primarily used Excel to help organize all the codes into their subsequent themes.

In the fourth step, I reviewed the themes. A first-level refinement was done to eliminate unsupported themes, combine them, and break down others. In the second-level refinement, I compared these overarching themes with the entire data set. The fifth step involved the finalizing and naming of these identified themes, which began once I created a solid thematic map representative of the data. The last step in this process was to produce a report on my findings.

The Effects of Space on Participation in Community Mental Health

Through my analysis I identified four major themes, each with various subthemes. Each theme relates to space and participation: inside the clubhouse, outside the clubhouse, stigma, and relationships.

A concept map of identified themes.

When looking at the theme of space and participation within the clubhouse, the three subthemes of member perspectives, provider perspectives, and overall space inside the clubhouse were identified. Members highlighted factors such as the fact that having high ceilings and one open space contributes to lots of noise, which challenges their ability to focus on daily tasks. However, this open space is also beneficial in feeling connected to everyone in the clubhouse throughout the day. Providers shared a similar sentiment with members within this theme, highlighting the use of large whiteboards that are easy to see and area-specific locations to organize tasks. Overall, the space inside the clubhouse radiates a positive and homey atmosphere that is well received by all participants.

The second theme of space and participation outside the clubhouse was also split into the same three subcategories of member perspectives, provider perspectives, and overall space outside the clubhouse. Members noted having many supportive and welcoming businesses within the walkable area surrounding the clubhouse, encouraging participation in outreach and fundraising events. Members felt an overall sense of support from the surrounding community, but there were some concerns about accessibility and the ability of some individuals to walk and participate in outdoor activities within this space. Providers shared many of the same ideas, highlighting that the connections to local businesses provide lots of opportunity for meaningful work to be done within the clubhouse that is interesting and engaging to members. The overall outside space is home to a variety of amenities and is noted for allowing personal errands to easily be run during the day.

The third theme of stigma was divided into two subthemes of inside and outside the clubhouse. A few members said that feelings of exclusion within the clubhouse were inhibiting their participation. Members who felt this way said that witnessing others’ self-stigma and not wanting to be recognized as part of the clubhouse influenced their own experience with self-stigma, decreasing their participation. Outside the clubhouse, there was an overall sense of neutrality within the neighboring businesses and apartments. Members did not report any stigma influencing their participation outside the clubhouse, simply coexisting in the same spaces together.

The last theme of relationships, space, and participation in the clubhouse was divided into subthemes of member and provider perspectives. Both members and providers revealed the impact of dealing with your own personal mental health struggles and sticking up for yourself. This caused different interpersonal issues between members in struggling to accept others' behaviors and faults at face value, and not taking those behaviors personally. Specifically, many members cited the issue of staff involvement and felt there was favoritism for certain members. They also voiced an overall lack of staff members to prevent and resolve all the interpersonal and relationship troubles, as an inhibitor to overall participation in the clubhouse.

Conclusion

The opportunity to complete the research project allowed me to gain important insights into the research process and learn about myself as a future clinician and researcher. In terms of conducting qualitative, mixed-method research, I was able to experience firsthand what it is like to immerse myself in a population. Smoothly engaging in this community was essential in maintaining the typical and casual environment of the clubhouse, to ensure that my data collection was authentic. Also, I now understand how to execute entry and exit from a site in an ethical way. This means building a rapport at a site before beginning a project, as well as remaining in contact with participants after your study and not vanishing after fully immersing yourself in their daily lives.

Personally, I improved my confidence and communication when working in a professional role. As a researcher, being confident when conducting semi-structured interviews and observations, and making decisions through the analytical process, is critical. As I complete my undergraduate degree this year and begin my journey toward earning my Doctor of Occupational Therapy degree here at the University of New Hampshire, I will use this project as a jumping-off point for my senior capstone. My research will help to fill a critical evidence gap within occupational therapy and science as well as the larger mental health literature about how space and the perception of it affects community participation and belonging for people accessing psychosocial rehabilitation. I look forward to continuing research in this area to better understand the mechanisms affecting participation in the mental health community.

My experience as a researcher and the skills I gained through this process will aid me when I transition into the role of a clinician. I always had an interest in working in mental/behavioral health, but through this experience my desire continued to grow. I can see myself thriving in an environment that is focused on mental and behavioral health. When thinking about my future field workplaces, this new insight has given me the opportunity and motivation to find sites that align with my passions.

I would first like to thank Dr. Nikhil Tomar for his guidance throughout this research project. I am incredibly grateful for his support through every step of the process. Without his mentorship and encouragement of me as a student researcher, my efforts would not have been possible. Thank you to my research site for their generosity in allowing me to conduct my research and to the members who participated in the study. I would also like to thank the Hamel Center for Undergraduate Research for providing me with this opportunity and my donors Dr. Dana Hamel, the Occupational Therapy 50th Anniversary Endowment for Undergraduate Research, and Ms. Catherine Latham for funding this project. Last, I would like to thank my family for their continued support of my academic and research endeavors.

References

Andonian, L. (2010). Community participation of people with mental health issues within an urban environment. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 26(4), 401–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2010.518435

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Byrne, T., Prvu Bettger, J., Brusilovskiy, E., Wong, Y.-L. I., Metraux, S., & Salzer, M. S. (2013). Comparing neighborhoods of adults with serious mental illness and of the general population: Research implications. Psychiatric Services, 64(8), 782–788. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201200365

Chen, F. (2017). Building a working community: Staff practices in a clubhouse for people with severe mental illness. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(5), 651–663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0757-y

Dorer, G., Harries, P., & Marston, L. (2009). Measuring social inclusion: A staff survey of mental health service users’ participation in community occupations. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(12), 520–530. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802209X12601857794691

Gonzales, L., Yanos, P. T., Stefancic, A., Alexander, M. J., & Harney-Delehanty, B. (2018). The role of neighborhood factors and community stigma in predicting community participation among persons with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services, 69(1), 76–83. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700165

Grob, G. N. (1994). Government and mental health policy: A structural analysis. The Milbank Quarterly, 72(3), 471. https://doi.org/10.2307/3350267

Hamm, J. A., Rutherford, S., Wiesepape, C. N., & Lysaker, P. N. (2020). Community mental health practice in the United States: Past, present and future. Consortium Psychiatricum, 1(2), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.17650/2712-7672-2020-1-2-7-13

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). (2022). Mental Health Information. Retrieved February 23, 2023, from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness

Tanaka, K., Craig, T., & Davidson, L. (2015). Clubhouse community support for life: Staff–member relationships and recovery. Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Mental Health, 2(2), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40737-015-0038-1

Tanaka, K., Stein, E., Craig, T. J., Kinn, L. G., & Williams, J. (2021). Conceptualizing participation in the community mental health context: Beginning with the Clubhouse model. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 16(1), 1950890. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2021.1950890

Terry, R., Townley, G., Brusilovskiy, E., & Salzer, M. S. (2019). The influence of sense of community on the relationship between community participation and mental health for individuals with serious mental illnesses. Journal of Community Psychology, 47(1), 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22115

Author and Mentor Bios

Sana Syed will graduate in May of 2024 with a bachelor’s degree in Occupational Therapy (OT) from the University of New Hampshire. She dove into her passion for OT with her research on utilizing the clubhouse model for treating severe mental illnesses. Sana’s interest in her research began with her volunteer work at a clubhouse and blossomed alongside her mentor, Dr. Nikhil Tomar, who works in a similar line of research. The Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) grant through the Hamel Center for Undergraduate Research allowed Sana to conduct this research, which she also used for her honors thesis. Sana learned through her experience with this research the challenges research protocol can present, but nonetheless appreciates her experience as she formed new connections and gained valuable knowledge. Sana’s passion for OT inspired her to publish with Inquiry as she believes in the journal’s importance to spread research findings to a broader population. After Sana graduates, she plans on staying at UNH to obtain her doctorate in OT, which she hopes to begin her professional career in mental health.

Dr. Nikhil Tomar is an assistant professor in the department of occupational therapy and started teaching at University of New Hampshire in 2018. He is a mixed methods researcher who specializes in the theoretical and empirical examination of stigma towards historically marginalized populations, such as those with mental illness, BIPOC individuals and/or sexual/gender minority individuals. Dr. Tomar met Sana when she was a student in his class, and he could tell she would be a dedicated researcher. He says that guiding Sana has been a good experience and that her dedication and focus on this research is admirable. Dr. Tomar describes Sana’s project as initiated through her own curiosities, rather than as part of a larger project. He also describes Sana as having great in interpersonal skills, making it “really fun to conduct research with her.” He hopes Sana’s peers see her experience and become motivated to undertake research that excites them and mobilizes their passion into a research inquiry.

Copyright 2024 © Sana Syed