Wildfires burned more than two million acres in the Amazon region in 2019.

In the summer of 2019, wildfires burned more than 2 million acres of the Amazon rainforest, a 77% increase over the previous year. To help predict whether such devastation is the region’s fire future, new UNH research will study fires from the Amazon’s pre-Columbian past.

“Our main goal is to better understand fires in Amazonia and if what we’ve seen the past few years is indicative of what’s happened long term in that forest.”

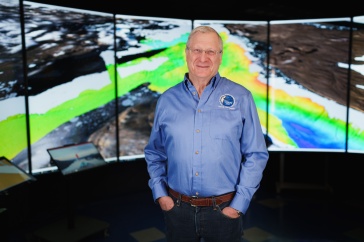

“Our main goal is to better understand fires in Amazonia and if what we’ve seen the past few years is indicative of what’s happened long term in that forest,” says associate professor of Earth sciences Michael Palace, principal investigator on the $600,000 NASA grant called “Smoke on the Water: Lake-based calibration of Amazonian fire histories.” Palace has been working in tropical forests for 25 years — 20 of them in Amazonia — on a variety of environmental research topics.

The interdisciplinary research team, which includes Jack Dibb, research associate professor in the Earth Systems Research Center, and former UNH postdoctoral researcher Crystal McMichael, now at the University of Amsterdam, will connect paleoecological clues from several thousand years ago with remote sensing data from the recent decades to determine what Palace calls a “fingerprint” of fire past, present and future. “We will also be using U.S. government spy satellites that collected data in the 1960s to look further back in time,” Palace notes.

The work has major implications not only for Amazonian forests and biodiversity but for Earth’s changing climate as well: The Amazon region is the world’s largest terrestrial carbon sink. “As these forests are lost or burned, this carbon turns into carbon dioxide and exacerbates any climate change,” says Palace, also in the Earth Systems Research Center within UNH’s Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space.

Although “it’s really hard to light a wet, tropical forest on fire,” Palace notes that humans have been doing so in Amazonia for millennia, exploiting drought years to expedite their efforts to clear the land for agriculture. Charcoal formed by those fires preserves well in soils and lake sediments and becomes a proxy measure of human activity in the 1,000 years before European contact.

“Our team will leverage previously taken cores of lakes and look at the layers of silt, sand and pollen grains to understand what the vegetation was like around those lakes and what the burn frequency was like,” says Palace.

If understanding the past means digging deep, studying recent fire activity has the researchers looking to the sky, harnessing remote-sensing and satellite data that show when, where and how hot fires burned around 53 lakes in the Amazon region. EOS research scientists Christina Herrick and Franklin Sullivan will work on the remote sensing component of the project.

The research team, which also includes Mark Bush of the Florida Institute of Technology, Eduardo Neves of the Universidade de São Paulo in Brazil and Doug Morton of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, believes this project could demonstrate the promise of an approach that links the disciplines of archaeology, ecology and paleoecology. “Because fire in Amazonia is so characteristic of human activity, so ecologically transformative, readily monitored from space, and reconstructed in paleoecological records, it is the ideal vehicle to use as our focus,” says Palace.

-

Written By:

Beth Potier | UNH Marketing | beth.potier@unh.edu | 2-1566