UNH students take part in a past Shoals Marine Laboratory event. Photo by Jeremy Gasowski

With recent news reports on the Trump administration’s move to open Atlantic waters to offshore drilling exploration raising concerns, two UNH experts shared their insights on a few key issues.

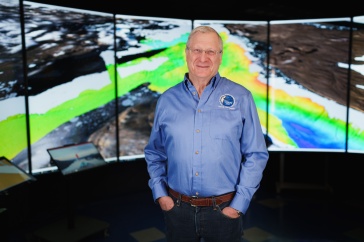

UNH’s Erik Chapman, director of New Hampshire Sea Grant and UNH Cooperative Extension's fisheries and aquaculture program leader and commercial fisheries specialist, weighs in on how such a move could impact local tourism and commercial fishing, while Nancy Kinner, professor of civil and environmental engineering, an expert in oil spill response and restoration, discusses what would have to happen for a plan to move forward, including aspects like mitigation.

According to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management's details on the process, the first of three proposals for the 2019-2024 National Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Leasing Program was released on Jan. 4, with comments being accepted through March 9.

At this stage in the process, Kinner says, “the key question is exactly where would that drilling occur? Unless conditions change a lot, the New Hampshire coast probably would not be the first place where drilling would be desirable — for a lot of factors.” Those include determination in an exploratory stage that sufficient amounts of oil exist and that it would be financially viable to move forward with production. The financial aspects include the drilling itself — getting a production rig out there — and having the infrastructure in place to deliver any oil being produced. “In the Gulf of Mexico, for example, a lot of that oil is pumped back onshore through pipelines. On the East Coast, we don’t have any offshore wells or the infrastructure. And that is a major investment,” Kinner explains.

Even before that, Kinner says, the process to move forward with any plan for leases would be a lengthy one, with permissions, permitting, lease sales, environmental-impact statements and mitigation and decommissioning plans.

“We’re talking years even without any court cases,” she says. But, she stresses, a long approval process does not mean there isn’t reason for concern. “I am saying there will be a process, and we need to be paying attention to that process.”

If such a plan moves forward, it would mean “vulnerability of our coastal resources to the effects of oil spills and other environmental hazards associated with drilling for oil in a marine environment,” says Chapman, who is a member of UNH’s College of Life Sciences and Agriculture department of biological sciences and the School of Marine Science and Ocean Engineering. “We have many examples of the kind of environmental and human catastrophes that result from accidents associated with offshore drilling with Exxon Valdez in Prince William Sound in 1989 and Deepwater Horizon in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010 being the best known. In New Hampshire, this would put our beaches, our tourism industry, fishing industry, emerging aquaculture industry — not to mention many of the things that give us such a high quality of life here on the Seacoast — all at risk.”

In response to the argument by proponents that expanded offshore drilling could be a step toward energy independence for the U.S., Chapman points to how such a move complicates marine planning discussions in a state where competing interests rely on a finite number of coastal miles. “It didn’t take long for our Republican governor and our Democratic senators to state their opposition to offshore drilling here, so it’s clear how they feel about how the cost-benefit analysis of this opportunity plays out for the state,” he adds.

Chapman notes the potential impact on New England’s commercial fishing and tourism economies cannot be ignored. “Groundfisheries off the coast of New Hampshire are already on life-support, given low quotas for some of the more valuable species, challenging markets that don’t always return a high price for catches and high operational costs,” he explains, “so the prospect of a devastating ecological disaster associated with an oil spill only makes prospects for this industry feel even worse. Lobstermen and recreational fishers are doing relatively well here, and they are just as much at risk. But I don’t think we can underestimate the devastation that could result from a spill for these industries given impacts we’ve seen from Exxon Valdez and Deepwater Horizon.”

The potential for a spill could prove to be a financial deterrent to expansion as well. “Oil companies have to have a plan for that as part of this process. They have to be able to show the ability to control if something goes wrong,” Kinner says. “Industry invested in a capping stack for the Gulf of Mexico. We don’t have that infrastructure anywhere off the Atlantic coast. This will be highly scrutinized.”

Could drilling happen?

“Yes, it could,” Kinner says. “Could it happen in the next couple of years? Probably not.”

Oil companies are only going to drill when they can make money, Kinner notes, stressing this process will be especially involved because these are not areas where drilling has occurred before. “The rules are set in law,” she adds. “The president can issue all the orders he wants, but the bureaucracy is set in place. I am not saying this isn’t serious. I am saying there are checks and balances, and we have a lot of time to be proactively resisting.”

Chapman echoes that sentiment. “For fishermen and people in the tourist industry, I think the first step is to learn about this issue in more detail,” he says, adding, “Organizations such as New Hampshire Sea Grant at UNH and other similar groups off-campus that are in the business of engaging stakeholders, providing information that enables informed decisions and facilitating discussion and convening expertise can work together to help support a sound and effective decision-making process.”

-

Written By:

Jennifer Saunders | Communications and Public Affairs | jennifer.saunders@unh.edu | 603-862-3585