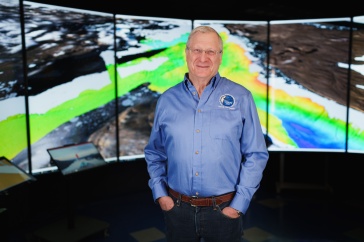

Prof. Nancy Kinner, seen here with two of her students, is in Russia this week presenting at an international symposium.

“We really need to understand this country and be able to work together to protect our mutual coastlines.”

That’s just one message Nancy Kinner, professor of civil and environmental engineering and co-director of UNH’s Coastal Response Research Center and Center for Spills and Environmental Hazards, is sharing while in Russia this week. Kinner is presenting two sessions at “Deepwater Horizon Well Blowout: Spill Response Lessons Learned — Effectiveness and Impacts” at the Gubkin Russian State University of Oil and Gas in Moscow. She spoke with UNH Today from Russia on the evening of her first session.

Bringing It Home

Prof. Nancy Kinner’s students have been following along with her in preparation for her trip to Russia and were able to connect with her on the eve of the symposium.

“I’ve been talking about going to Russia with them since the beginning of the semester,” she said.

While Americans may have preconceived notions about Russia from media portrayals, understanding the reality is essential, she added.

“Interacting with the people is terrific, and we all want a common good for the environment. Those are really heartening things to think about,” she said.

Two of Kinner’s teaching assistants, who were checking in with her via the call, echoed that enthusiasm.

“I think it’s fascinating,” said Taler Bixler.

Melissa “Missy” Gloekler added, “I think it’s quite impressive to have an advisor/professor who is in such a global setting.”

UNH’s Center for Spills and Environmental Hazards and WWF-Russia are partnering for this symposium to “create an awareness of cooperative oil spill response in the Arctic – especially in areas where the U.S. and Russia share a border,” Kinner explained from her hotel late Tuesday evening, Moscow time.

The list of symposium attendees includes participants from Russian and U.S. government agencies and institutions, NGOs, scientific institutions, businesses and the media. “We have to work together on this issue because, at its closest point in the Bering Strait, there are only 56 or 57 miles between the U.S. and Russia, and they are very treacherous waters,” Kinner said of protecting the Arctic in the event of an oil spill due to increased shipping routes or, in the future, drilling. “We’re trying to get this dialogue moved along.”

This topic is not new to Kinner. In addition to being a sought-after expert on oil spill mitigation here in the U.S., her paper, “Efforts by NGOs To Foster Greater Cooperation on Oil Spill Response, Damage Assessment, Restoration and Communication Between Russia and the United States,” co-authored with Alexey Knizhnikov of World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Russia and Elena Agarkova Belov of the WWF United States Arctic Program, will be released at the 2017 International Oil Spill Conference in May.

Her first session, set for the next afternoon, would focus on the use of dispersants, which she explained was very limited in the U.S. prior to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010. Their use was one takeaway she hoped to share with attendees. Among the tools she hopes will become more widely adopted is the Environmental Response Management Application, commonly referred to as ERMA, developed at UNH in cooperation with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, an online mapping tool that integrates data to assist in spill preparedness and coordinating response efforts.

“It is very, very difficult to treat spills. It’s very difficult to understand the impact of those spills, and so we’ve done a lot of thinking about that post-Deepwater Horizon — with the lessons that we’ve learned from Deepwater Horizon and the hundreds of millions of dollars of research — and which of those lessons are applicable to the Arctic.”

In addition to ecological concerns in the Arctic, there are concerns for longterm impact on humans.

“One thing we learned a lot about in Deepwater Horizon was about the interaction of oil and dispersed oil with seafood and how to test for it,” she explained. That is especially important when considering the impact of a spill on indigenous peoples in the Arctic who depend on seafood and marine mammals for their subsistence.

There are also concerns about Alaska’s food safety, food security and commercial fishing industry in the event of a spill. “We really need to be thinking about how can we test the seafood and how can we assure the American people that the seafood is safe," she said.

Ultimately, Kinner stressed, “We can’t ignore that border, and we need to think about how can we work cooperatively.”

-

Written By:

Jennifer Saunders | Communications and Public Affairs | jennifer.saunders@unh.edu | 603-862-3585