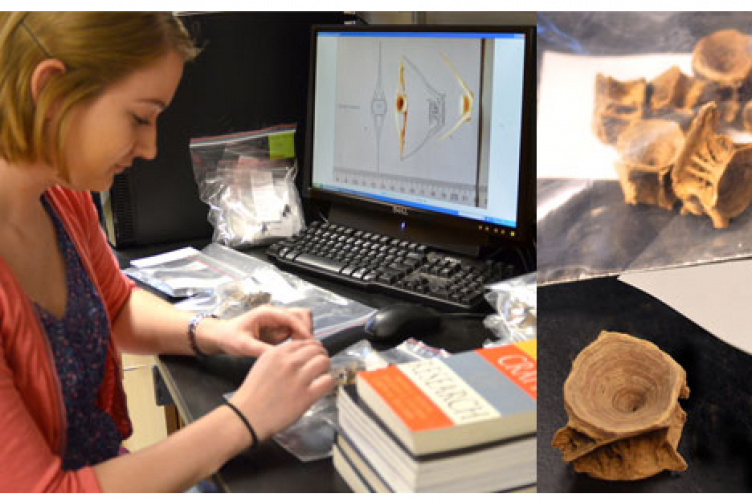

Courtney Mills, UNH anthropology major, working with Atlantic cod vertebrae from the Seabrook archaeological site excavated in the mid-1970s.

Where most people see just a bunch of old fish bones, Courtney Mills sees snippets of the ocean’s storied past and tiny clues to a pressing environmental conundrum. Mills, a senior anthropology and history major, is studying codfish bones from nearby archeological sites to learn more about New England’s codfish population. Her work comes at a crucial time in the industry and may offer some valuable data to fishery management experts.

“Currently the codfish stocks in the Gulf of Maine are depleted. It’s really big in the news,” said Mills, who will present her work at the Undergraduate Research Conference, a two-week long symposium that began last Friday. “The New England Fishery Management Council voted to cut back on codfish catches by 77 percent for 2013. That’s a huge cut for them.”

While industry experts say the decision was crucial to the future of the species, it will hit hard for New England fishermen and those who rely on their catch. Mills hopes her work will help scientists figure out what’s going on with the cod population and how to restore it. “It’s important to understand that this issue is nothing new,” said Mills, who studied fish bones ranging in age from 250 years old to as old as 2,000 years old alongside Meghan Howey, assistant professor of archaeology. “Fishery Management really just looks at contemporary data. But we can learn a lot by looking at what the population used to be hundreds and even thousands of years ago.”

Using bones from a Seabrook site that was dug in 1974 and 1976, as well as two sub sites, Mills has conducted several tests to uncover important facts about cod history. Using a process called stable isotype analysis to measure the amount of carbon 13 in the bones, she determined that cod have been caught in larger numbers near shore than offshore for some 450 years. “You can see this switch in the archeological record, from being caught offshore to being caught near shore,” she said.

Mills also ran tests comparing vertebrae from two refuse pits, one dated at about 950 years old and one dated at about 250 to 450 years old (around the time when settlers arrived). “In both cases, cod vertebrae have shrunk over time,” she said. “Typically when fish are being overfished, their size decreases.”

Mills is one of more than 1,300 undergraduates whose work is featured in the 14th annual Undergraduate Research Conference and one of many whose research will benefit New Hampshire organizations or populations.

“The students are doing authentic research in classrooms, laboratories and out in the field in a variety of places,” said Julie Williams, senior vice president of engagement and academic outreach at UNH. “Some of them can have a really big community impact.”

Many students are working on specific, practical projects alongside members of the community, Williams said, while others are conducting research that could eventually be used in their fields. Even those whose research appears fairly arcane at face value are better preparing themselves for careers in which they can make important contributions.

Briana Traynor, who is in the five-year Masters of Education program, has spent the past several months designing an arts integration curriculum for elementary school students – a project she hopes can be used by area teachers to invigorate their subject matter.

Using the new Common Core standards for second grade, Traynor designed a curriculum unit called Coming to America. For one lesson, students will read a book about a boy who comes to America from Africa: “He describes that one thing he’ll never forget about his home country is how the colors are so rich,” Traynor said. After reading the book, students will listen to African music and paint with whatever colors the music brings to mind. For another lesson, students will learn about the Statue of Liberty, talk about what it symbolized for new Americans and make their own monuments out of clay.

“There are so many benefits to using the arts to teach content,” Traynor said. “The kids are constantly building their own meaning. They’re connecting it to their own lives. It especially helps students who have a hard time expressing themselves. The arts really unlock content for those kids.”

Traynor got to see the benefits of arts integration firsthand earlier this year when she and her faculty adviser, Raina Aimes, went to a local school and taught a unit on Pompeii and volcanoes. They did a volcano dance, wrote a play about Pompeii and made volcano artwork. “The teachers were pretty open to it and amazed at what their kids could do,” Traynor said. “When they saw the kids interacting with the content in a different way, it was almost like seeing all new learners.”

While Traynor is concocting creative lesson plans, Patricia Halpin’s microbiology students are working with a different kind of culture. Serving as interns at the water treatment plant in Manchester, they test the city’s water supply for contaminants such as heavy metals, pathogens and organic contaminants.

The work gives the five seniors valuable experience in assessing water safety, compiling data and complying with state and federal regulations, said Halpin, a professor of biology at the University of New Hampshire at Manchester. It’s also hugely important to public health.

“They’re really the first line of defense in insuring we have clean drinking water,” Halpin said.

The conference is one of the largest and most diverse in the country.

Originally published by:

UNH Today

Written by Sarah Earle

-

Written By:

Staff writer | Communications and Public Affairs