The University of New Hampshire is a flagship research university that inspires innovation and transforms lives in our state, nation and world. More than 16,000 students from all 50 states and 71 countries engage with an award-winning faculty in top ranked programs in business, engineering, law, health and human services, liberal arts and the sciences across more than 200 programs of study. UNH’s research portfolio includes partnerships with NASA, NOAA, NSF and NIH, receiving more than $100 million in competitive external funding every year to further explore and define the frontiers of land, sea and space.

UNH Researchers Provide Technology for Next-Generation Weather Satellites

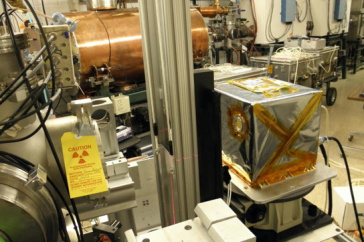

Energetic Heavy Ion Sensor (EHIS); space weather instrument designed built and calibrated the University of New Hampshire for the GOES-R weather satellite.

DURHAM, N.H. – State-of-the-art space weather instrumentation developed by researchers at the University of New Hampshire Space Science Center was launched into space Nov. 19 at approximately 6:42 p.m. EST from Cape Canaveral, Florida. The technology is part of a suite of weather instruments created specifically for the new leading-edge National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) weather satellite. Known as the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite-R, or GOES-R, it was developed to provide more accurate weather forecasts and warnings.

Researchers at UNH were contracted to design, build and calibrate the Energetic Heavy Ion Sensor (EHIS), part of a suite of four space weather instruments called the Space Environmental In-Situ Suite (SEISS). The sensor will allow scientists to monitor over long periods the level of energetic ions, from protons to nickel, that populate near-Earth space environment. These ions are the main cause of radiation damage in space to both electronic and biological systems. High levels of radiation can impact many things from communications and GPS satellites, to commercial airlines and space travel for astronauts.

“An increased heavy ion environment near Earth, which signals higher radiation risk, can affect something as basic as airline altitude,” said Clifford Lopate, research associate professor at UNH and principal investigator on the project. “Being able to forecast a higher radiation risk for so-called “polar” planes that tend to fly at higher altitudes near the Earth’s poles would allow airlines to warn pilots and reroute planes to lower altitudes to decrease the risk of long-term exposure to radiation for their crews, who fly the same route over and over again.”

GOES-R, NOAA’s biggest satellite advancement to date, will provide National Weather Service forecasters the meteorological equivalent of going from black and white to ultra-high-definition color TV. The new satellite can deliver vivid images of severe weather as often as every 30 seconds, scanning the Earth five times faster, with four times greater image resolution and using triple the number of spectral channels compared with today’s other GOES spacecraft.

GOES-R’s advanced imagery and higher resolution will enable improvements to NOAA’s hurricane tracking and intensity forecasts, as well as the forecasting of severe weather including tornadoes, thunderstorms and flooding. In addition, GOES-R’s space weather sensors will improve NOAA’s ability to monitor the sun and forecast space weather, including the detection of radiation hazards.

The team of engineers, led by Lopate and James Connell, an associate professor at the UNH Space Science Center, constructed the sensor to specifically measure atomic nuclei in space from helium, through the more massive carbon, nitrogen and oxygen, and the very massive iron and nickel. Like the rest of the universe, the large majority of positively charged particles in space are protons, followed by helium, then the heavier elements. Monitoring these particles has become an integral part of the NOAA Space Weather program that tracks and forecasts changes in the environmental conditions in space around the Earth. The EHIS is the first UNH designed instrument to be included in an operational satellite payload.

Latest News

-

December 4, 2025

-

November 26, 2025

-

November 6, 2025

-

November 5, 2025

-

October 24, 2025