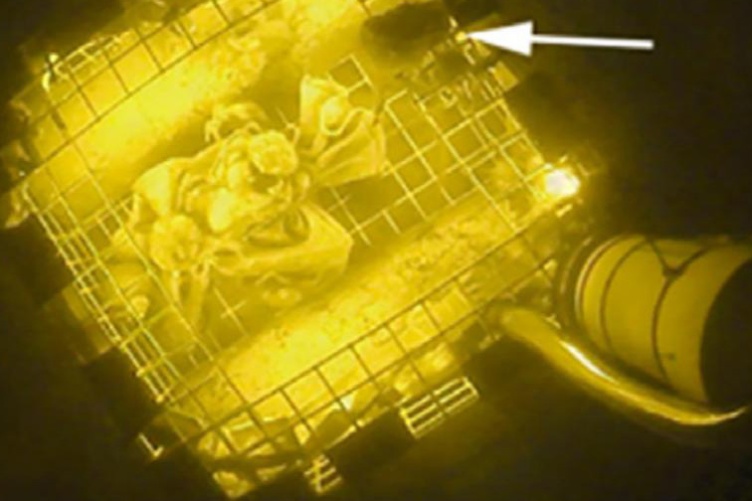

A channeled whelk (white arrow) enters a trap at night. The trap has an attached camera to observe whelk movement and behavior.

Few business sectors are feeling the heat of recent years more directly than the commercial fisheries along the New England coast. Waters in the region are warming at rates among the fastest on earth, and important species are under stress, including lobster that are facing increased disease and declines in reproduction. In response, University of New Hampshire (UNH) researchers are working with producers to hone strategies for sustainable fishing of a different kind of edible sea life, the channeled whelk, based on their findings about how the whelks’ circadian clocks and environmental cues affect their activity.

Channeled whelks are nocturnal feeders, but their activity depends on a mix of innate circadian rhythms and environmental cues important for efficient trapping.

Channeled whelks, a kind of large, carnivorous snail, are uncommon fare in the U.S., limited to specialty markets in large cities. They are a bigger hit with diners overseas, however, and the whelk fishery is worth about $5 million annually in Massachusetts alone. Importantly, areas along the New England coast that are losing their lobsters are at the northern edge of the channeled whelk’s range.

“Are the whelk migrating north? Well, they’re snails, so it would take quite a long time,” says Elizabeth Fairchildwith a laugh. “But the New England whelk fishery is becoming more important.”

Fairchild, a research associate professor of biological sciences at UNH, is leading a team studying the channeled whelk’s biology and bait preferences. In addition to expanding biological knowledge, the findings bolster the growth of a viable and sustainable whelk fishery. The latest research is published in Journal of Shellfish Research.

Sustainable bait

The current channeled whelk fishery extends from Cape Cod south to the Carolinas. Fishing is done with traps equipped with bait sacks to attract the bottom-feeding whelk. Prior research, as well as anecdotal evidence from fishermen, suggested that channeled whelks are largely nocturnal, with most entering the traps after dusk.

Fairchild’s research, begun with students Shelley Edmundson ‘16G and continued by Mary Kate Munley ’21 ‘23G in Fairchild’s lab, has focused largely on the bait used in the traps. Each fisherman tends to have a unique preferred whelk bait mix, but all include horseshoe crab, widely regarded to be an essential ingredient. Unfortunately, horseshoe crabs are under considerable ecological pressure, so the research team has worked to create a more sustainable and highly effective horseshoe crab-less bait.

“We work closely with the fishermen, who are scientists in their own right,” says Fairchild. “They’re excited about some of the things that we’ve learned, but they won’t adopt new baits or methods unless they’re cost-effective and better than what they have now.”

Timing is everything

whelk to track its movements.

Knowing more about the natural behavior of the whelks is an important part of developing better baiting strategies. Edmundson had previously collected visual data using “whelk TV,” time-lapse footage of whelk behavior once they’d entered the traps. Fairchild describes the footage as a “night-time underwater nightmare” of fast-moving crabs and slow-moving whelks swarming the feed bag, with only the whelks remaining by dawn. Formal field analysis in the current study confirmed the prior observations of nocturnal feeding, with far more whelks captured after dark than during the day.

“In addition to the bait itself, we need to know the best ways to work with it. Exploring whelk behavior and movement shows us how we might do a better job of attracting them to the traps.”

But the researchers turned to the laboratory to learn more about whelk behavior by studying it under three scenarios. In one, the whelks were housed in the UNH Coastal Marine Laboratory’s flow-through tanks. Seawater from the mouth of the adjacent Piscataqua River flows through the tanks, and many of the marine environmental conditions, such as cyclical tidal and temperature variations, are maintained. The second scenario placed whelks in a static, controlled seawater environment at a constant temperature. The third housed them in a similar static, controlled environment, but in smaller containers with “speed bumps” made with PVC pipes cut in half and attached to the bottom. For all, whelk movement was measured in both light/dark cycle and fully dark conditions.

The results indicate that channeled whelks do indeed have their own circadian clocks that influence movement even in environmentally controlled conditions. At the same time, they also exhibit sensitivity to environmental cues, such as tidal rhythms. In the ocean, therefore, their movements and behavior likely depend on a complex interplay between their internal clocks and external conditions. Understanding the forces at work provides the best chance for knowing where and when whelks are most likely to be on the move.

“In addition to the bait itself, we need to know the best ways to work with it,” says Fairchild. “Exploring whelk behavior and movement shows us how we might do a better job of attracting them to the traps.”

-

Written By:

Mark Wanner | College of Life Sciences and Agriculture | Mark.Wanner@unh.edu