Left to right, Kabria Baumgartner, Northeastern University historian, and Meghan Howey, University of New Hampshire archaeologist, at the dig site of what archeologists believe is the home of King Pompey. Photo credit: Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University.

Archaeologists at the University of New Hampshire along with a historian at Northeastern University believe they have unearthed the long-lost homestead of King Pompey, an enslaved African who won his freedom and later became one of the first Black property owners in colonial New England.

“We are thrilled,” said Meghan Howey, professor of anthropology and director of the University of New Hampshire’s Center for the Humanities. “I’m extremely confident this is a foundation from the 1700s and everything that points to this being the home of King Pompey is very compelling.”

“King Pompey was an esteemed leader in the Black community but his home and property have always been a mystery,” said Kabria Baumgartner, dean’s associate professor of history and Africana studies at Northeastern University. “I spend a lot of time in archives looking at written materials so to be on site and see this revealed has been exciting.”

Example of river rocks altered to form a foundation found in the four-foot trench at the dig site of what archeologists believe is the home of King Pompey. Photo credit: Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University.

.

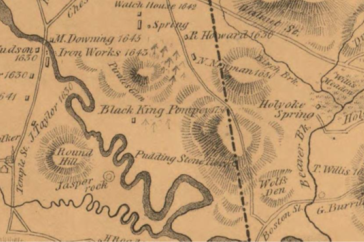

The researchers from the two different universities collaborated and shared resources to dig deep and locate what they believe to be the homestead of Pompey Mansfield on the banks of the Saugus River, where he lived with his wife Phylis (or possibly named Phebe) over 260 years ago. Historical accounts portrayed him as a prominent community leader who bought land, built a stone house in Lynn and hosted free and enslaved Blacks from the region on “Black Election Day”.

Also known as “Negro Election Day”, it was one of the most important days in the colonial era for Black people in New England and was where Pompey was elected king on an annual basis. The event was documented as lively and joyful with dancing and singing based on their West African traditions. It was held on the same day that white men voted for their leaders. The highlight of the day was voting for and crowning a king, who could later be called on to handle important matters in the Black community. Similar celebrations took place throughout New England and the rest of the Americas, including states like New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Connecticut.

To pinpoint the location, the archaeological team, which included archaeologist Alyssa Moreau and community historian Diane Fiske with UNH’s Great Bay Archaeological Survey, spent months pouring over public records, deeds and genealogical records. They compared historical maps with contemporary LIDAR-derived topographic maps and cross-referenced them with probate records and historical newspapers to identify specific landmarks and narrow down the area.

In a trench that was four-foot deep, the team uncovered a foundation that was constructed of river rocks as described in the documentation. They had to dig through layers of several different eras of newer foundations covering the 1700s structure to reveal it. Below the trash, concrete and mortar, the team discovered a layer of smaller, smooth stones from the nearby tidal river that had been chiseled and layered so they fit together. All point to something that someone with limited resources would have done at the time to build a home.

“The big find was the handmade pebble foundation without quarry rock,” said Howey “That showed determination and ingenuity. And then the compelling match of the historical descriptions, the bend in the river, marshy meadow, oak trees. While not everything in history is written down, or even written down correctly, when it comes to what people leave behind, they don’t edit their trash.”

“I've always been fascinated by those fleeting private and intimate moments outside of the watchful eye of an enslaver when Black people could be themselves and enjoy each other and be in community,” said Baumgartner. “It’s rare for me to get a chance to be on the site of a discovery and thanks to Meghan and her team’s archeological work we get a better sense of King Pompey’s world. It was just as described, serene and peaceful.”

Researchers are hopeful to eventually work with the National Park Service to establish a historical marker about King Pompey and do more outreach and exhibits that share the story and the figures of Black Election Day.

Funding was provided by the New England Humanities Consortium (NEHC) and Northeastern University.

-

Written By:

Robbin Ray ’82 | UNH Marketing | robbin.ray@unh.edu | 603-862-4864