Key Facts on UNH Composting

- Food waste from UNH dining halls (Philbrook and Holloway) and the UNH Memorial Union Building (MUB), as well as select residence halls and apartments, is transported to Kingman Research Farm for composting.

- On average, 25,000 to 40,000 pounds of food waste are collected per month during the academic year, resulting in over 200,000 pounds composted annually.

Key Terms

Closed-loop composting: System in which all food scraps and other organic material generated on campus are composted on-site.

Waste pulpers: Machines that grind and pulverize organic waste, drain out water content, and produce dry waste that’s sent to the composting site.

Windrow composting: Method of composting that involves piling up long, narrow rows (or windrows) of organic matter. Through regular turning of the piles, the organic matter receives greater oxygen flow and moisture while also redistributing the hotter and cooler portions to create ideal temperatures for composting.

At the 360-acre Kingman Research Farm, out past the old farmhouse, the Office of Woodlands and Natural Areas and acres of plots growing cucurbits, corn and cover crops, sits a large field with rows upon rows of what appears to be dirt. About 8 feet wide and 4 feet high, these “dirt” rows look rather unremarkable, apart from the occasional bits of food and dead plants sticking out. However, about a foot beneath the surface, temperatures reach a scalding 130 degrees Fahrenheit as various reactions break down the waste, turning it into nutrient-rich soil.

The NH Agricultural Experiment Station-operated Kingman Research Farm is just one part of UNH’s robust composting program, which began in the mid 1990s. The operation starts in UNH’s dining halls, where the emphasis is on reducing the overall waste streams by providing tools and information that minimize pre- and post-consumer waste (i.e., the amount of waste returned on diners’ plates and trays). On the post-consumer side, some of these methods include purchasing denuded (fat-trimmed) beef and growing some of the produce right on campus, including at two high tunnels managed by the Farm to YoU NH program and located adjacent to the Fairchild Dairy Teaching and Research Center. On the post-consumer side, methods include signage that encourages the importance of portion control to reducing waste, the use of serving spoons that are sized for single portions of the food they dish out and the Wildcat Plate with information on portion sizes.

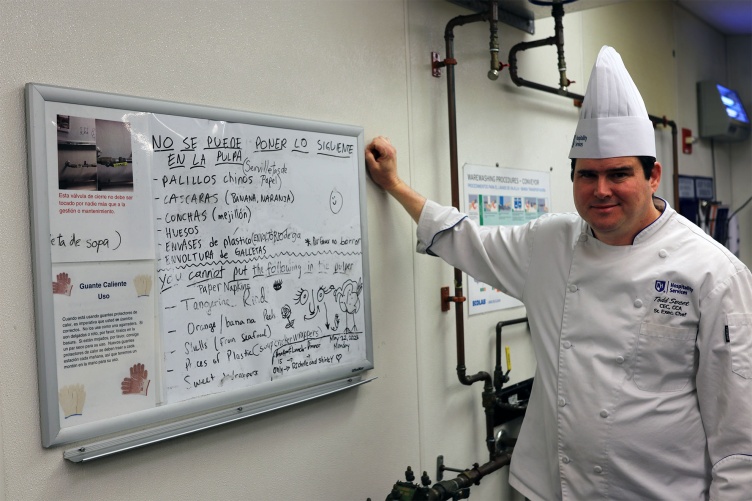

“In our most recent tray-return survey, which was conducted pre-COVID, we found that there was an average of 1.7 ounces of food waste per entry [to the dining hall],” described Chef Todd Sweet, assistant director of culinary with UNH Hospitality and Campus Services. “And we find ways to minimize that by cooking to order, portion control, methods like that.”

“Because our composting program at UNH is integrated into our dining program—allowing us to weigh waste as it comes out—it provides us the opportunity to reduce that output ultimately,” Sweet added.

Rochelle L’Italien, registered dietitian nutritionist with UNH Dining Services, said that food waste is also diverted through donation to the UNH Food Repurposing Project—a collaborative effort with the Portsmouth-based Gather food pantry.

“The dining halls and UNH Catering donate wholesome overproduced food to the Food Repurposing Project, which converts that and other rescued food items into meals for community members facing food insecurity,” L’Italien added. “This not only reduces the amount of food that may have been at one time sent to be composted, it also serves a basic human need for food and nutrition.”

During the academic year at UNH, about six to eight 55-gallon buckets worth a day of compostable waste per dining hall gets sent to the Kingman Research Farm. Once loaded into the truck, the buckets are driven out to the Kingman Research Farm by UNH Dining Services students during the academic year and UNH Dining Services staff in the summer. In the academic year, the compostable material—from 1,500-2,000 pounds—is delivered five days a week.

Once at the Kingman Research Farm, the material gets dumped into an open section of windrow and then covered over by UNH farm manager Evan Ford or a member of his team. The 220-cubic-yard windrows initially begin with bedding and manure from UNH’s equine facilities. Ford and his team pile that material into rows, begin mixing in the compostable waste and occasionally turn the material to allow for greater aeration and temperature distribution. After a year, the compost is complete and ready to be applied to the research fields at Kingman and the Woodman Horticultural Research Farm.

“The program here at UNH really highlights that even without large investments into infrastructure and labor that a composting program can be implemented by the Granite State’s smallest towns and villages to ultimately reduce waste and provide a nutrient-rich additive to gardens and farms.” ~Anton Bekkerman, director, NHAES

“We’re essentially breaking down horse manure and food waste so that we can apply it to our crop fields,” said Ford. “We’ll add it to fallow fields that are not being used for growing that season to help enrich the soil.”

“The composting work here is really a University-wide effort,” he added. “It involves our partners at UNH Dining Services, Health & Wellness, Farm Services and more to utilize the waste so it doesn’t just go to a landfill.”

Anton Bekkerman, director of the NH Agricultural Experiment Station, said that UNH’s closed-loop composting program offers evidence that such an effort can be implemented by small-scale communities, municipalities and other institutions in New Hampshire.

“The program here at UNH really highlights that even without large investments into infrastructure and labor that a composting program can be implemented by the Granite State’s smallest towns and villages to ultimately reduce waste and provide a nutrient-rich additive to gardens and farms,” said Bekkerman, an associate dean in the College of Life Sciences and Agriculture.

The compost created on campus is only used for UNH farms and is not available to purchase.

-

Written By:

Nicholas Gosling '06 | COLSA/NH Agricultural Experiment Station | nicholas.gosling@unh.edu