UNH scientists are taking part in a study to learn more about the microbes that break down organic matter and manmade contaminants in the ocean and subterranean desert environments.

A $6 million research grant was recently awarded to the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, in collaboration with UNH and the Desert Research Institute, to develop the tools and genetic technologies necessary to study single-celled bacteria that influence the biogeochemical cycles in different ecosystems. This innovative research will connect the genetics of individual microbes to their roles within the environment in near-real-time. Funding for the grant was provided by the National Science Foundation’s EPSCoR Research Infrastructure Improvement Program.

“The bacterial breakdown of manmade contaminants like oil and plastic in the ocean becomes more and more of an issue as the levels of contamination increase."

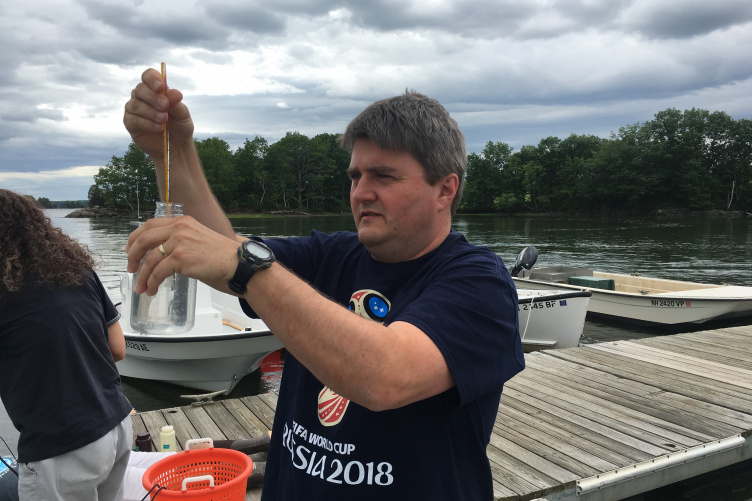

“Very little is known about the efficiency of microbially-mediated degradation of organic matter and manmade contaminants in the sea,” says Kai Ziervogel, a UNH research assistant professor of marine biogeochemistry who is taking part in the study. “We know they exist but we don’t know which bacteria are involved in breaking down carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorous, and we don’t know how fast the bacteria take up these compounds which are important for many biological processes in the sea.”

Ziervogel - who is part of UNH's Ocean Process Analysis Laboratory - will focus on microbes from the coastal Gulf of Maine, an ecosystem that is not immune to the effects of pollution.

“The bacterial breakdown of manmade contaminants like oil and plastic in the ocean becomes more and more of an issue as the levels of contamination increase,” Ziervogel says. “Frankly, we know even less about the biology and ecology of microbes that ‘eat’ contaminants compared to those that ‘eat’ algal products.”

Here is where the new tools developed by this research group will come in to play: Ziervogel will partner with Erik Berda, UNH associate professor of chemistry and a collaborator on this grant, to place a fluorescence marker on specific molecules that chemically resemble a particular type of contaminant. The microbes that break down the contaminant will take up the marker, thus enabling the researchers to identify which bacteria are the ones that are capable of the degradation.”

In addition to the anticipated technological advances, this grant will provide funding for two UNH students — one graduate student and one undergraduate — to learn more about these topics.

“I am excited that this project will provide students with opportunities to participate in interdisciplinary research that will contribute to environmental science in a unique way,” Ziervogel adds.

-

Written By:

Rebecca Irelan | Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space | rebecca.irelan@unh.edu | 603-862-0990