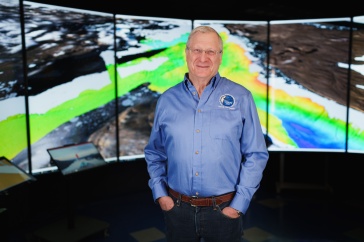

Kellen McArthur '19 pulled up sediment cores from beneath Arctic lakes in Sweden to learn more about how the climate has changed over time in those ecologically sensitive regions.

Buried deep in the muck beneath ancient Arctic lakes, there are clues that can help scientists learn what the climate was like thousands of years ago — and what it could be in the future.

Kellen McArthur ’19G is piecing together this historical record as part of his master’s degree in geology with the UNH Department of Earth Sciences. Ruth Varner, UNH professor of Earth Sciences and Director for The Leitzel Center and the UNH Earth Systems Research Center, serves as his advisor. McArthur spent two weeks above the Arctic Circle this past April collecting samples of sediment cores from the bottom of three lakes. This area, part of the Stordalen Mire Complex, is dotted with lakes and permafrost — the latter of which is thawing more frequently in recent years due to climate change.

McArthur is focusing on the region because it is and has long been sensitive to change and, therefore, could provide a good record of environmental and climate changes. Sediment cores offer a glimpse into the past because they hold layers of pollen, dust, algae and other small particles that drift to the bottom of the lake over time, creating layers that tell a story.

“I love geologic history for the perspective it provides,” McArthur says. “If you know what has happened in the past with the climate at the mire, it’s possible that you could predict what will happen there in the future.”

In order to collect the samples that he’s now analyzing, McArthur traveled to Sweden this past spring with Joel Johnson, UNH associate professor of geology, and Eric Heim ‘18G, who received his Master of Science degree in geochemical systems.

The logistics of field sampling are not always easy, particularly in remote areas like the Arctic. And it’s difficult to drill for lake sediment cores from a boat because the vessel moves around too much, McArthur explains, so the samples had to be taken when there was still ice on the lake to serve as a solid platform. Although there is a research station near the field sites, the team still needed to get their sampling equipment out there, and so they pulled their equipment on a sled through the snow for about a mile. Once there, the team worked long days using an ice auger to drill 50 holes by hand.

“We worked until the blades were dull and my arms were sore,” McArthur recalls with a slight laugh.

The team brought the cores back to the research station, packed them into insulated core boxes and then shipped them back to UNH for cold storage in the lab until McArthur began working on the samples this summer.

He split the cores down the middle using a Dremel saw, peeled the two sides apart and began his work. The cores are mostly gray with occasional thin stripes of brown or black, bits of gravel or a tiny stick here and there. Using a toothpick, McArthur takes small bits of the muck, smeared it on a microscope slide and dried it out on a hotpad to firm up the single-celled algae called diatoms for viewing under the scope.

"If you know what has happened in the past with the climate at the mire, it's possible that you could predict what will happen there in the future."

If the lakes were warmer in past millenia, there could be more photosynthetic diatoms, he explains, peering through the microscope. He pushes his chair back and gestures at the slide: It is filled with tiny shapes of the single-celled algae.

He carefully draws with colored pencils in his thick leather-bound journal, creating a visual record of the color changes, small rocks and sticks and other noteworthy characteristics in each sediment core.

“That is the old way of doing things, the geologist’s way, to make a drawing of something,” McArthur says. “I like that approach. We have instruments to measure all sorts of things, but the drawing puts that data into context.”

In collaboration with James Haney, UNH professor of biological sciences, McArthur is testing out a new technique measuring the fluorescence (emission of light) of chlorophyll and phycocyanin (blue pigment from blue-green algae) preserved in the sediments. They hope this technique will help describe the biological production within the lakes at any given time, as well as the conditions and climate outside the lake that influence the lake’s production.

“My job is to figure out why these changes happen,” McArthur says. “It’s a little bit like being a detective.”

-

Written By:

Rebecca Irelan | Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space | rebecca.irelan@unh.edu | 603-862-0990