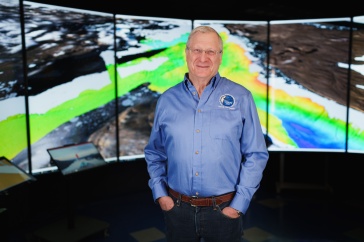

University of New Hampshire doctoral student Ryan Cassotto is measuring glacier speed in Greenland

Courtesy Photo

It only sounds like a joke: When the world’s fastest-moving glacier sped up in the summer of 2012 – suddenly surging from Greenland’s west coast at four times its 1990s rate – UNH doctoral student Ryan Cassotto was there. Now, he’s parlayed that bit of scientific serendipity into a prestigious NASA fellowship and research that could shed light into the rate of sea-level rise over the next century.

Greenland’s Jakobshavn Isbrae glacier is a tidewater glacier – a tongue that sticks out from the ice sheet into the ocean via a deep, narrow fjord. "They're ice streams, if you will, these fast moving channels of ice that branch off from main ice sheet," Cassotto says.

Glaciers are constantly on the move, but tidewater glaciers are especially speedy, advancing each day by meters instead of the more typical centimeters. And since 2012, Jakobshavn Isbrae has been zipping along at a blistering 60 meters per day. It’s a trend, says Cassotto; over the past decade, the entire margin, or outer edge, of the massive ice sheet that covers 80 percent of Greenland’s surface has accelerated its march to the sea.

Because tidewater glaciers are especially effective at delivering ice into the ocean, climate scientists have them in their crosshairs. For two weeks in the summer of 2012, a research team including Cassotto and his co-advisor Mark Fahnestock, affiliate research professor in UNH’s Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans and Space and a professor at the University of Alaska, headed out to the terminus of the Jakobshavn Isbrae with a new instrument that measures glacier speed with much greater precision than satellites.

“We were able to make observations of the record-breaking changes on time scales previously not possible,” Cassotto says of the instrument, called a ground portable radar interferometer. The UNH-owned instrument took 10,000 measurements over the course of two weeks; previously, satellites measured the glacier’s progress just once every 11 days.

Now, Cassotto is analyzing that treasure-trove of data to understand a simple yet important question: Why did Jakobshavn Isbrae speed up? It’s a question NASA, which awarded him the Earth System Science Fellowship, also wants to answer as researchers seek clues to the complex relationship between the glacier and the ocean.

“Ultimately, sea level rise is one of the implications,” Cassotto says. As the glacier retreats and speeds up, it increases the rate at which it’s putting ice into the ocean. What’s more, if that ice isn’t replenished by snow upglacier, it effectively reduces the overall size of the Greenland ice sheet, which has additional implications for the ice sheet’s stability and Earth’s energy balance.

And because Greenland’s glaciers are changing faster than those at the South Pole, “this is a precursor or a prediction of what we can expect to happen in Antarctica,” he says.

Cassotto, who is also advised by assistant professor of geology Margaret Boettcher, anticipates that the NASA fellowship will fund the remaining few years of his doctoral studies, during which he’ll continue to analyze the data he collected that serendipitous summer of 2012.

"I was quite fortunate to get this grant to be able to use this dataset, process it, then make it available to the public through the National Snow and Ice Data Center," he says. “Ultimately, we want to understand how the ice and the ocean interact. It’s all about getting a better view of what the glaciers are doing.”

-

Written By:

Beth Potier | UNH Marketing | beth.potier@unh.edu | 2-1566