Scientists from UNH and around the globe have published the most detailed map to date of the Arctic Ocean seafloor, which they hope will provide a glimpse of the geologic features that could affect global climate, the melting behaviors of the Arctic ice sheets, and ultimately influence sea level rise.

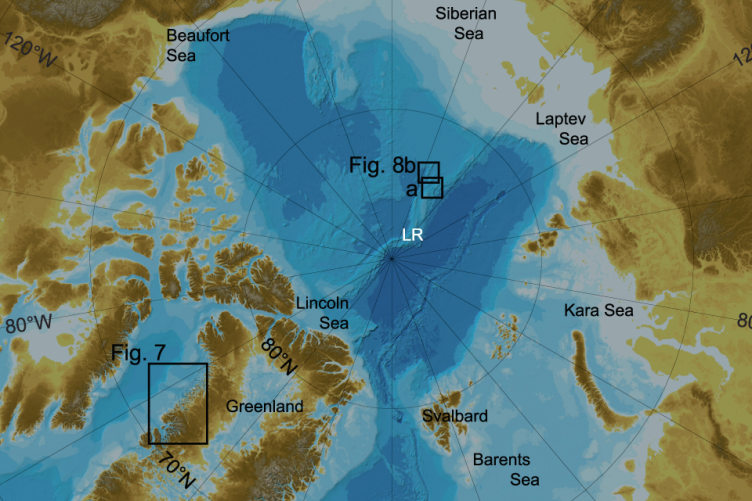

Using all available depth data, including new state-of-the-art multibeam sonar technology, and sometimes surveying areas never before explored by ship, the new compilation now has approximately 19.8% of the Arctic Ocean seafloor mapped, representing a 13% increase from the previous chart compiled in 2012. This improvement is result of many expeditions and mapping campaigns, including the Ryder 2019 Expedition north of Greenland which was co-led by Larry Mayer, director for the UNH Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping (CCOM), and Martin Jakobsson, professor at Stockholm University in Sweden and affiliate assistant professor at CCOM.

A description of the new digital depth data compilation was recently published by the group of researchers from 15 countries in the Nature journal Scientific Data. The chart is the newest version of the international bathymetric chart of the Arctic Ocean (IBCAO) project, which began in 1997 in Russia. Jakobsson is the current IBCAO chairman.

“The Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping at UNH is proud to be a participant in the release of this new map of the Arctic,” Mayer says. “The increased resolution and coverage of this new map represent a great step forward in our understanding of the geologic and glacial history of the Arctic Basin, and that has many implications for improved understanding of future changes.”

Scientists and explorers have long pursued Arctic travel and mapping despite — or perhaps because of — its inherent challenges. As the Arctic Ocean experiences longer periods of ice-free conditions, ships are now better able to navigate through that region, allowing scientists to study the world’s northernmost water body and ocean basin in more detail than ever before. To that end, Mayer and other researchers from CCOM have made significant bathymetric data contributions in recent years, mostly aboard the U.S. Coast Guard icebreaker HEALY where they mapped the seafloor to help establish the limits of U.S. jurisdiction in the Arctic under the Law of the Sea Treaty. Mayer then joined forces with Jakobsson aboard the Swedish icebreaker ODEN for the 37-day Ryder 2019 Expedition in northern Greenland.

According to Jakobsson, the ODEN was the first ship to ever enter the Sherard Osborn Fjord in northern Greenland where the Ryder Glacier drains. The region north of Greenland has been very poorly mapped, he says, because of the harsh sea-ice conditions in the Lincoln Sea that make it nearly impossible for all but the most powerful icebreakers like the ODEN to navigate.

The shape of the seafloor can have a major impact on how deep currents flow and when glaciers and ice sheets will melt, which can then impact sea levels. Jakobsson underscores the importance of gleaning this information and ensuring it’s as precise as possible.

"The increased resolution and coverage of this new map represent a great step forward in our understanding of geologic and glacial history of the Arctic Basin, and that has many implications for improved understanding of future changes."

“The behavior of the marine components of glaciers and ice sheets represents the single largest uncertainty in assessing the future of global sea levels,” he explains. “We need better bathymetry to reduce that uncertainty, to predict the future retreat of the Greenland Ice Sheet in a warming climate and its contribution to sea-level rise.”

Mayer and Jakobsson have a history of Arctic map collaboration outside of the Ryder 2019 Expedition: in 2015 they participated in another expedition on the ODEN, to Petermann Glacier, also in northern Greenland. In addition, UNH and the University of Stockholm co-host the Arctic-North Pacific Regional Center within the Nippon Foundation-GEBCO Seabed 2030 Project — an ambitious initiative to map the entire world’s seafloor by the year 2030. The IBCAO initiative is now supported by the Seabed 2030 Project as it provides resources to compile all the depth data from the Arctic Ocean within the Arctic-North Pacific Regional Center.

“The production of this new Arctic Ocean map, which has increased the coverage from 6.7% to 19.8% of the Arctic, has made an important contribution to this goal of mapping the entire world ocean seafloor, but there is still a long way to go,” Mayer says.

“North of Greenland, offshore of the fjords, there are huge areas where no one has ever been with ships thus far,” Jakobsson adds. “I hope we can put together a new expedition and go beyond where we were in 2019 and gather more data. Sweden and the U.S. have had an excellent collaboration around our icebreaker ODEN, through the Swedish Polar Research Secretariat and U.S. National Science Foundation, and I hope this can continue.”

The Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space (EOS) is UNH's largest research enterprise, comprising six centers with a focus on interdisciplinary, high-impact research on Earth and climate systems, space science, the marine environment, seafloor mapping, and environmental acoustics. With more than $58 million in external funding secured annually, EOS fosters an intellectual and scientific environment that advances visionary scholarship and leadership in world-class research and graduate education.

-

Written By:

Rebecca Irelan | Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space | rebecca.irelan@unh.edu | 603-862-0990