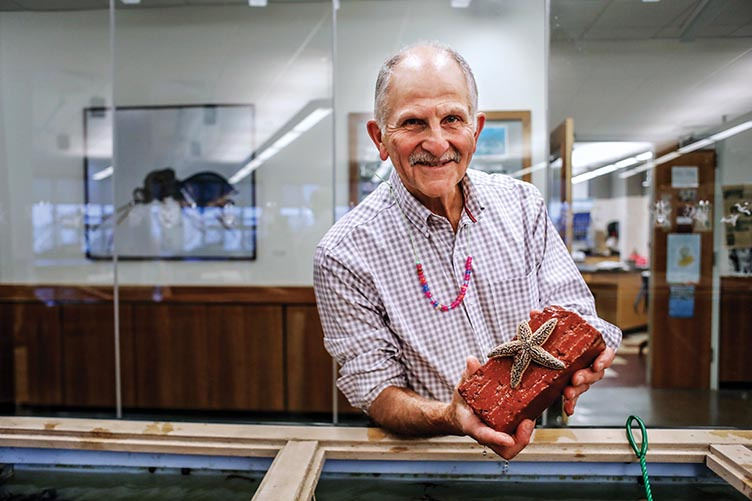

Rich Aaronian ’67

More than halfway through his fifth decade of teaching science at Phillips Exeter Academy (PEA), Rich Aaronian ’67 is the prestigious private school’s longest-tenured instructor — but he balks at the suggestion that longevity makes him a legend. “I appreciate it, but I’m not sure I’d consider myself much of a legend,” he says.

Watching Aaronian in action during PEA’s family weekend last fall, however, the honorific seems justified. As their smartly dressed parents look on, the 13 students making up one of Aaronian’s freshman biology classes break into small groups to review the previous night’s reading — an essay by the late physician Lewis Thomas titled “Organelles as Organisms” — then gather round an oval table to share their thoughts as a group. While they discuss, posing questions to one another and responding with answers or questions of their own, Aaronian circles the sun-filled room, pausing near a skeleton sporting heart-shaped sunglasses and a flamingo hat to take in a protracted exchange about prokaryotes and eukaryotes, mitochondria and chloroplasts. When the class members finally turn to Aaronian for a question they can’t resolve among themselves, he responds not with the answer but with a salient line from the essay that causes several students’ faces to light with comprehension.

“Oh!” one exclaims. “So he’s saying that some of our most important organelles were once independent organisms.”

Like every PEA instructor, Aaronian teaches using something called the Harkness method, which entails turning much of the “teaching” over to the students, with minimal lecturing — or answer-giving — coming from the instructor. It’s a deceptively challenging approach that requires absolute command of subject matter and a deft touch regarding when and how to guide a class of intelligent, driven teens.

Aaronian joined the PEA faculty in 1971, after earning a zoology degree from UNH and an eventful stretch that saw him finish a year of graduate work in Florida, teach at Hampton’s Winnacunnett High School, complete basic training for the Air Force and marry his UNH sweetheart and fellow ’67 grad, Peg. He was back at UNH, continuing his graduate degree, when he saw the PEA job posting for a part-time science instructor pinned to a bulletin board in Spaulding Hall.

“I thought it would be good for a few years,” he says with a laugh. Instead, he and Peg spent 14 years living in the dorms and raised their two sons on campus. “I never imagined I’d still be here 47 years later. But Exeter really grows on you.”

He grew on Exeter, as well. Shortly after joining the faculty full-time, Aaronian introduced both marine biology and ornithology to the curriculum; inspired, he says, by the great exposure he gained to both subjects at UNH. Raised in Medford, Massachusetts, and the first member of his family to attend college, he developed a bond with his freshman adviser, zoology professor emeritus and ornithologist Art Borror. Borror turned him on to birding and instilled a passion for fieldwork and conservation that he’s passed along to his own students. “I’ve always loved the field aspects of biology and observing organisms in their natural habitats,” he says. “It’s something I impress upon my students: Nothing in science can begin until you see something.”

Today, there are hundreds of Aaronian’s former students who credit him with their decision to pursue careers in science — particularly ornithology. His impact has been recognized with honors as diverse as a cameo in 1982 PEA alum Dan Brown’s book “Angels and Demons” and a 2018 Goodhue Elkins Award from the New Hampshire Audubon Society for his contributions to the study of New Hampshire birds.

And as for that pesky l-word, legend?

During the Exeter family weekend freshman biology class, as the students transition from discussion to lab work, a parent introduces himself to Aaronian as a 1990 PEA graduate who had himself been in Aaronian’s class three decades earlier. Told Aaronian is being profiled by UNH, the alum/ parent offers an unprompted assessment:

He should be,” he says. “He’s a legend.”

-

Written By:

Kristin Waterfield Duisberg | Communications and Public Affairs