Researchers gather to dedicate neutron monitors atop Haleakalā on Maui.

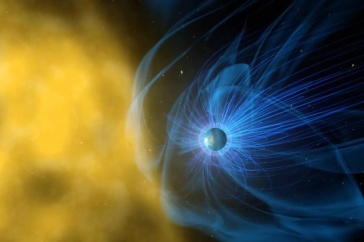

For the last 19 years, there’s been a gigantic hole in the solar cosmic ray monitoring network near the equator of the Pacific Ocean. As powerful particles streamed out of sun flares and reached the Earth, this gap — stretching from Thailand to Mexico City — meant that scientists were missing out on recording crucial space weather data they needed to effectively study and forecast space storms that can knock out power grids and affect GPS and satellite communications.

But now, high atop the summit of Haleakalā on the island of Maui, scientists have installed equipment which effectively restores the cohesive, worldwide monitoring network that once existed, using the same simple-but-effective technology as it did almost two decades ago.

As Jim Ryan stood there on Haleakalā, looking at the equipment he helped to build over the past year, he was filled with an overwhelming sense of gratitude. Ryan, a UNH professor emeritus of physics, has not fully retired in large part because of this project, which he finds utterly fascinating and critically important. The project is funded by the National Science Foundation and led by the University of Hawai’i in collaboration with UNH.

Haleakalā has a particular site advantage from which to measure neutrons — particles that don’t have a charge to them but can still impact our technology — coming from the solar flares: Its 10,023-foot elevation provides a longer daily sun exposure, and its low latitude means that the sun is nearly straight overhead throughout the year, so Haleakalā is directly in the path of neutrons.

“We really have to have the whole Earth peppered with neutron monitors, and we’re trying to do our part with the U.S. bringing the neutron monitor on Haleakalā back on the system — it should make a dramatic improvement [in our space weather modeling efforts],” Ryan explains.

Malcolm Colson and Andrew Kuhlman are both UNH Ph.D. students who are studying space physics topics related to neutron monitors. Ryan, who serves as their graduate advisor, tapped their expertise for this project. They worked alongside UNH research engineer Jason Legere in Durham to build the neutron monitor, rewrite the data acquisition software and run tests to ensure it was working properly. Colson and Kuhlman traveled to Haleakalā this past winter and spring to hook up the monitor and its electronics, making sure everything was ready to come back online.

Even though their research typically deals with the theoretical side of space physics, both students noted their surprising satisfaction with the build.

“It was really great to create a neutron monitor from scratch,” Colson says. “Being able to say we were here for the whole process of getting it off the ground, of building something with my own hands, it’s a good feeling.”

Kuhlman agrees. “Having the opportunity to do something hands-on where I’m creating an instrument to study space science and getting to see and use the equipment in person is really cool,” he adds.

Neutron monitors were an early specialty of the UNH Space Science Center, Ryan notes. When the Center was in its infancy 60 years ago, researchers were working on installing a neutron monitor on Mount Washington, which has detected numerous large solar events since that time. It’s still in operation today, he says, noting that neutron monitors can reliably record data for many decades, making them a good investment to create long-term data sets.

The reason behind the 19-year monitoring gap on Haleakalā is complicated and caused by a confluence of factors including funding challenges, Ryan explains. But he prefers to focus on moving the science forward now that the system is back up and running; he’ll be interpreting the data as it starts to roll in from space weather events.

Ryan says he is thrilled that there’s a renewed interest in using this tried-and-true technology. “What’s old is new again, it’s all coming back around,” he adds, smiling

-

Written By:

Rebecca Irelan | Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space | rebecca.irelan@unh.edu | 603-862-0990