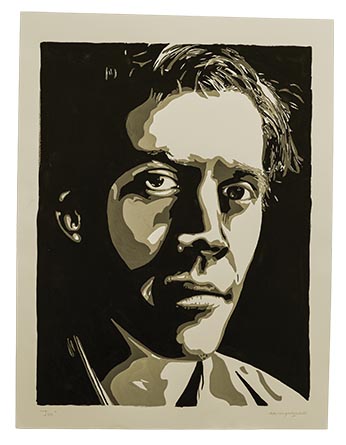

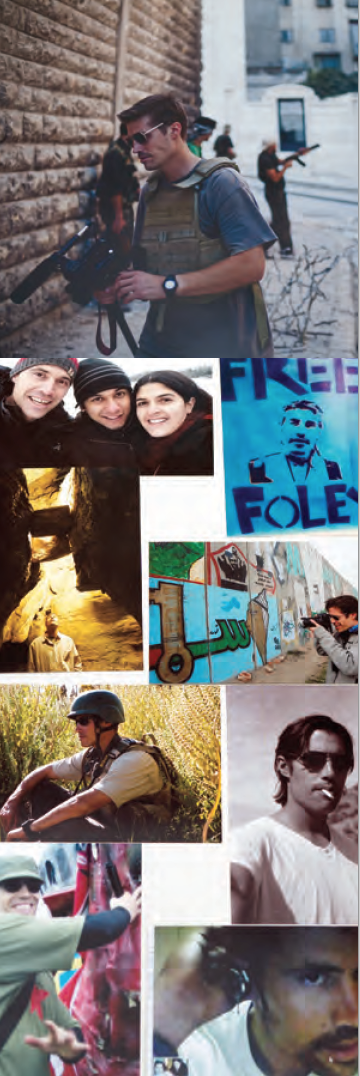

AS DIANE AND JOHN FOLEY ’70 settle into the bright and airy living room of their Wolfeboro, New Hampshire, home on a breezy, blue-skied August morning — Diane seated on the end of a semi-circular couch and John in a blue-and-white striped armchair opposite her — they are flanked by an array of framed family photos, more than a dozen in all.

On a built-in bookshelf in the corner of the room. On the mantel over the fireplace. On the shelves of a hutch beside sliding glass doors that open to a sunlit deck. The images throughout are of their five children at various stages of their lives, including their eldest.

That’s Jimmy.

A meandering 40-minute drive away in Rochester is the office of the James W. Foley Legacy Foundation, where Diane Foley’s desk is cluttered with teetering stacks of paper beneath fluorescent lights and faded ceiling tiles stained brown by old leaks.

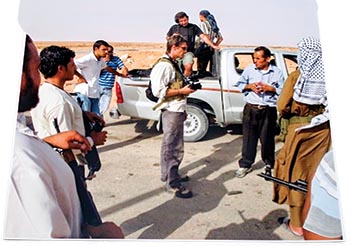

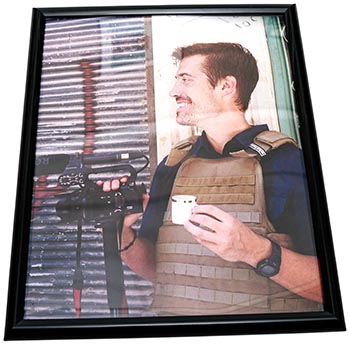

On the walls and shelves surrounding her here are more images and artifacts related to her eldest. College degrees and academic accolades, professional commendations and photos of a young man — camera in hand, sunglasses on and protective vest strapped to his chest — working as a journalist in war-torn regions around the world.

That’s Jim.

IT’S BEEN FIVE YEARS SINCE JAMES FOLEY, 40, WAS MURDERED IN THE RAQQA REGION OF SYRIA AFTER NEARLY TWO YEARS HELD CAPTIVE, BEHEADED BY ISLAMIC STATE MILITANTS ON AUG. 19, 2014, IN A VIDEO THAT WAS SEEN AROUND THE WORLD.

Foley was working as a freelance journalist at the time of his capture.

Diane and John had always known Jimmy, the affable, kind, independent firstborn child who would habitually check in with weekly Sunday phone calls even as an adult and take his parents out for coffee whenever he returned home from his domestic and international work.

But he rarely delved too deeply into the details of the work he was doing. Only over the course of the last five years have the Foleys come to fully realize a picture of Jim, the devoted, change-minded, uncompromising man who was compelled to repeatedly return to dangerous environments to tell the stories of those he felt otherwise didn’t have a voice.

In many ways, Diane and John have learned alongside the rest of the world about the full impact Jim made, through the very public lens of his tragic death.

“We’ve gotten to know Jim as an adult after his death, and that’s been a journey for us,” says John. “We didn’t know all the good he was doing as a human being.”

Adds Diane: “Jim was busy doing his own thing — he was always very independent. We really had no idea how many lives he’d touched. It was only after his death that we really came to understand that.”

And it was his death — and that now fully revealed selfless approach to life — that stirred Diane to similarly try to touch as many people as possible in Jim’s honor. Within weeks of his passing, the family had formed the James W. Foley Legacy Foundation, which has since significantly influenced the way hostage rescue operations are handled by the U.S. government and seeks to advance how journalists are educated and trained to enter war zones and other dangerous situations.

“We’re representing Jim’s legacy in many ways, so it’s important for us to be able to represent the things he believed in,” says Amy Coyne, director of corporate and community relations at the Foley Foundation. “We never really realized how much people thought of Jim until after he died, and for all those people, he touched their lives so dramatically just by being present in it. So it’s important for us to represent him, his family and the organization the way that he would want.”

Even beyond the inescapable sorrow following Jim’s death, helping the foundation blossom hasn’t been easy for the Foleys. It’s been trying for Diane’s husband and children to operate without her for extended stretches at times as she pours herself fully into the foundation’s work — she’s jetted back and forth to Washington, D.C., seemingly countless times for meetings and events, and has made numerous international trips, as well.

“I would say in some ways I got to know my mother after Jim’s death, too. With her persistence, her vision, her leadership — when even people in the family were saying, ‘mom, just stop; just be a mom,’” says John Jr., Jim’s younger brother and the only Foley child on the foundation board. “But through her persistence and her intestinal fortitude and the necessity to value journalism and bring Americans home, the foundation was born, literally, on her back.”

Diane understands the challenges her family has faced as the foundation has flourished, but she knew immediately that helping others in similar situations was the only outlet that would truly allow her to cope.

“It’s been hard on my family, but I think they have come to understand more and more why this has been my path to healing — that I couldn’t really find healing by hiding,” Diane says. “I had to channel my outrage and grief into something positive for somebody else. Jim has challenged me to find some good to come out of this.”

Getting to Know Jim

To hear Jim Foley tell it, at least to his parents, he was a disaster as a teacher and mentor.

Foley spent his childhood in Wolfeboro and graduated from Kingswood High School before attending Wisconsin’s Marquette University as an undergrad, majoring in history and minoring in Spanish. Upon graduation he applied to both the Peace Corps and Teach for America, choosing a position with the latter as it put him in inner-city Phoenix, where his Spanish language skills would be put to use, rather than Africa, where the Peace Corps intended to send him.

Jim worked with a population of largely Hispanic and Native American students in a challenging environment where graduating from eighth grade was a significant achievement. And from the reports Diane and John received, it … did not go well.

“All we would hear was on Sunday when he’d call us and tell us what a lousy teacher he was,” Diane says. “He said they had a ‘We hate Mr. Foley’ fan club, that they’d throw their textbooks in the trash. He would tell us all about the antics the students would do.”

What he didn’t tell them, they would come to learn, was that he was actually connecting with his students in a lasting and meaningful way; a way that many had not yet experienced with an adult. He got to know them as individuals. He coached basketball.

Years later, after his death, one of his former students — without knowing the Foley family — started the Foley Foundation of Phoenix, since renamed the Phoenix Foley Alliance to avoid confusion with the family’s foundation, to provide scholarships for students in inner-city Phoenix.

Diane and Jim’s sister, Katie, visited the area not long after the Alliance was created.

“We were blown away,” says Diane. “Oh, the stories. Jim was there for three years, and after he left he still mentored those kids from wherever he was in the world, until he died.”

This quickly became a pattern for the Foleys — discovering that the truth about Jim’s professional adventures hardly matched the humble history he had provided. They were excited for him to move to Chicago to pursue a master’s degree from Northwestern University’s prestigious Medill School of Journalism; they didn’t know he was teaching writing to young felons in the Cook County Sheriff’s Boot Camp program for nearly four years while he was there. They certainly knew he was embedded as a freelance journalist in Syria several years later; they didn’t know he was also working to raise money for an ambulance for the Syrian village he was in at the same time.

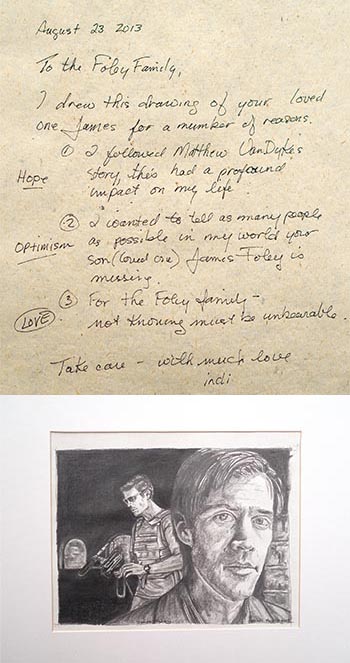

“We didn’t know most of what he was working on, or we’d just hear snippets,” Diane says. “When he was home, he was just my beloved Jimmy.” It didn’t take long after his death for his impact to become apparent. Within weeks of the news, money began “pouring in from all over the world,” John says. One letter arrived from England mere days after news of Jim’s passing became public. The family had three huge buckets set up at the house to collect all the mail and donations. And this, indirectly, helped lead to the start of the foundation.

“We got mail and donations from all over the world, so it was almost like that propelled us to do something with it, do something to remember Jim that would make a difference for others going through what we went through,” Diane says.

Spurred in part by the spontaneous donations from strangers around the globe, the foundation was formed within three weeks of Jim’s death, no small miracle given the legal red tape necessary to make an entity of that type official. But, truth be told, the idea was conceived much faster than that.

“Within a half hour of Jimmy’s death, once we first stopped crying, Diane said, ‘He’s not going to die in vain,’” John recalls.

The outpouring of support and determination to create something positive out of a devastating situation weren’t the only factors fueling the Foleys to push for change, though. They were also reacting to the overwhelming frustration they’d encountered throughout the process of trying to bring Jim home — and were determined not to let other families experience the same exasperation.

Frustration and Loss

Thanksgiving Day 2012 is when everything changed. Diane and John didn’t hear from Jim — who was working as a freelance journalist in Syria at the time — that day, which Diane found “ominous” given the consistency with which he checked in on holidays, regardless of where he was in the world. The next morning the family received a call from one of Jim’s colleagues, who told them that Jim had been kidnapped a few miles from the Turkish border.

The FBI reached out and encouraged the Foleys to remain quiet. They obliged. Christmas passed. So did the New Year. As the weeks mounted, the lack of communication and shared information eventually became too much.

“There’s always that big tension between going public and not going public, and there are advantages and disadvantages to both, but finally the silence was so deafening we couldn’t stay quiet anymore,” John says.

Diane soon quit her job as a nurse and began making monthly trips to Washington, D.C., searching for information, but there wasn’t a designated person or even department assigned to handle Jim’s case that she could lean on.

Remarkably, Jim had been held captive once before: in March 2011 he and several colleagues were kidnapped in Libya by Colonel Muammar Gadaffi’s regime, in an incident that resulted in the killing of photojournalist Anton Hammerl. But that kidnapping — which would end with Jim’s release 44 days later — was witnessed by New York Times reporter C.J. Chivers, so there was knowledge regarding the prisoners’ whereabouts.

There were no such witnesses in Syria.

“No one observed the kidnapping, and no one knew who the kidnappers were,” Diane says. “He just vanished.”

If the FBI had more information than that, it didn’t make its way to the Foleys. Even when leads mercifully emerged, help was hard to come by and progress was slow. Nearly 11 months into Jim’s captivity, in October 2013, Diane discovered a missed Skype call from a man in Belgium claiming his son had seen Jim. The government left it to Diane to respond, so she reached out and learned that the man’s son had been in jail with Jim and fed him and his fellow captives. Jim befriended him — “because Jim could make friends with a doorknob,” John quips — and the man promised his family would reach out to Jim’s when he got home.

It was the first signal that Jim was potentially alive, though it ultimately didn’t lead to any progress in freeing him. The next critical lead came — chillingly — directly from the captors, who sent an email to Jim’s brother Michael that November. The message demanded 100 million euros — $132 million — or the release of all Muslim prisoners. The captors offered proof of life, so Michael quickly came up with three questions that only Jim could have answered, and all three came back “right on,” Diane says. Finally, the Foleys had tangible proof that Jim was alive.

The FBI encouraged the Foleys to be honest about the fact that they couldn’t pay the ransom, but when that message was shared after about a month of intermittent contact, the captors cut off communication completely.

What’s more, Diane and John say they were told “directly and indirectly” by the U.S. government that if they negotiated with the captors or tried to raise the ransom, they would be prosecuted, an approach Diane says she found “appalling.”

Meanwhile, hostages from other nations began to be released. While the Foleys were on a family trip to Disney at the end of February 2014, several Spanish hostages were granted their freedom. French prisoners eventually followed.

Then, in June 2014, one of the last remaining non-American prisoners to be set free was Daniel Rye Ottosen, a young Danish man who reached out to the Foleys within 24 hours of his release because he had something to share: a letter he’d memorized after Jim had asked him to deliver it to his family.

The message begins with recollections of times Jim had with his parents, contains personal messages to each of his siblings and details the ways in which Jim and 17 other prisoners had bonded in a single cell, over “endless long conversations about movies, trivia, sports” and makeshift games of checkers, chess and Risk.

“I know you are thinking of me and praying for me. And I am so thankful. I feel you all especially when I pray. I pray for you to stay strong and to believe. I really feel I can touch you even in this darkness when I pray,” the letter says.

“We knew it was right from Jim’s heart, because it was just ‘him,’” Diane says.

That emotional lift was ultimately short-lived, however. Later that month, the Foleys received the first message from Jim’s captors in nearly a year, this time threatening to kill Jim if the U.S. government didn’t stop bombing parts of Syria. The Foleys had started trying to raise the ransom demanded by the captors early in 2014 and were near the $1 million mark when communication was cut off once again.

Then, on the morning of Aug. 19, 2014, FBI agents appeared at the Foleys’ door unannounced and swabbed their mouths for DNA samples. Later that morning, Diane and her sister were in the kitchen when Diane received a phone call from a sobbing AP reporter, asking if she had been on Twitter.

Diane went online and discovered an image of her son immediately after he’d been killed. She’s never seen the video.

In search of answers, the Foleys called the FBI, but didn’t receive a response (they believe Jim had already been killed when the FBI visited them in the morning, but that suspicion has never been confirmed). It wasn’t until President Obama went on television that night and announced to the world that Jim had been murdered that the Foleys received official confirmation.

Despite trying to navigate the overwhelming grief that followed, the foundation was active less than a month later and the Foleys were soon working to ensure that no other family had to endure what they did.

“We were shocked and appalled at how our situation had been treated by our government that we had trusted. I felt as Americans we had to do better,” Diane says. “Jim was always a very optimistic young man — he was always looking for the silver lining, always looking to help others — and so I just felt a huge challenge to right this horrible wrong we had experienced.”

Foundation for Change

Righting that wrong would require influencing a fundamental change in the way hostage negotiations were handled by the U.S. government, no small task for a fledgling organization operating out of a tiny office hundreds of miles from Washington.

But that’s precisely what unfolded. In the wake of several other American captives being killed within a year of Jim, the Foleys, through the foundation, became vocal participants in a growing chorus that ultimately prompted the National Counterterrorism Center to do an independent evaluation of how the country handled hostage negotiations.

The result, through an Obama administration executive order in June 2015, was the creation of the Hostage Recovery Fusion Cell, an inter-agency operation housed at the FBI responsible for full-time work on hostage cases. Just as important to the Foleys, established as part of the process was a family engagement team charged with providing focused support to affected families. A special State Department envoy was also created to assist in diplomatic negotiations.

Since 2014, at least 20 hostages detained around the world have been safely released. Fueled in part by that success, the foundation has continued to experience consistent growth in its first five years — in terms of impact, at least. The staff remains remarkably small, with only Diane and Amy Coyne working full-time in New Hampshire. Margaux Ewen joined the team as executive director in March, based in Washington, D.C., where she can interact face-to-face with Congress and U.S. hostage families, as well as the White House.

Ewen, an attorney, came to the foundation from Reporters without Borders because the mission aligned closely with her outlook.

“I always wanted to help people. I wanted to know that what I was doing had moral clarity and we were doing good, and I 100 percent feel that is what we’re doing here,” she says.

Jim’s final letter to his family was dictated to and memorized by a fellow prisoner in Syria, who shared it with his family upon his release.

Dear Family and Friends,

I remember going to the mall with Dad, a very long bike ride with Mom. I remember so many great family times that take me away from the prison. Dreams of family and friends take me away and happiness fills my heart. ¶ I know you are thinking of me and praying for me. And I am so thankful. I feel you all especially when I pray. I pray for you to stay strong and to believe. I really feel I can touch you even in this darkness when I pray. ¶ Eighteen of us have been held together in one cell, which has helped me. We have had each other to have endless long conversations about movies, trivia, sports. We have played games made up of scraps found in our cell . . . we have found ways to play checkers, chess, and Risk . . . and have had tournaments of competition, spending some days preparing strategies for the next day’s game or lecture. The games and teaching each other have helped the time pass. They have been a huge help. We repeat stories and laugh to break the tension. ¶ I have had weak and strong days. We are so grateful when anyone is freed; but of course, yearn for our own freedom. We try to encourage each other and share strength. We are being fed better now and daily. We have tea, occasional coffee. I have regained most of my weight lost last year. ¶ I think a lot about my brothers and sister. I remember playing “werewolf” in the dark with Michael and so many other adventures. I think of chasing Mattie and T around the kitchen counter. It makes me happy to think of them. If there is any money left in my bank account, I want it to go to Michael and Matthew. I am so proud of you, Michael, and thankful to you for happy childhood memories and to you and Kristie for happy adult ones. ¶ And big John, how I enjoyed visiting you and Cress in Germany. Thank you for welcoming me. I think a lot about RoRo and try to imagine what Jack is like. I hope he has RoRo’s personality! ¶ And Mark . . . so proud of you too, bro. I think of you on the West Coast and hope you are doing some snowboarding and camping, I especially remember us going to the Comedy Club in Boston together and our big hug after. The special moments keep me hopeful. ¶ Katie, so very proud of you. You are the strongest and best of us all!! I think of you working so hard, helping people as a nurse. I am so glad we texted just before I was captured. I pray I can come to your wedding . . . . now I am sounding like Grammy!! ¶ Grammy, please take your medicine, take walks and keep dancing. I plan to take you out to Margarita’s when I get home. Stay strong because I am going to need your help to reclaim my life.

Jim

The foundation hosts two signature events each year — the James W. Foley Freedom Run (a 5K run/walk in Rochester, New Hampshire, a 1.5 mile fun run in Washington, D.C., and a “virtual” run/walk featuring participants from all over the world) and the James W. Foley Freedom Awards dinner, held each spring in Washington, D.C., to honor individuals whose work reflects the foundation’s values and mission.

Those values and that mission are reflected in partner groups the foundation has played a critical part in conceiving and nurturing, too. In early 2015, the foundation played a key role in the formation of Hostage US (partnering with the Ford Foundation to help fund the start of the organization), a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit organization that provides individual support and guidance for U.S. hostages families and returning hostages.

It also was influential in the creation of the ACOS Alliance (A Culture of Safety Alliance), a group uniting various news and freelance journalist organizations to “champion safe and responsible journalistic practices” for freelancers and other journalists. The ACOS Alliance helps facilitate things like insurance and critical safety training for freelancers who might otherwise not have access to such support.

That focus on journalist safety has become an important pillar of the foundation over the years. It has partnered with the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern — where Jim earned his graduate degree — to develop a graduate curriculum on the subject, and in partnership with Marquette this fall is rolling out the pilot of a module-based curriculum for undergraduates, which outlines ways for journalism professors to incorporate information about journalism safety and preparation into existing lesson plans.

The program is being overseen by Tom Durkin, the foundation’s education program director and a friend of Jim’s since their freshman year at Marquette.

“Journalism is changing. Young journalists can be targets, and students and instructors really need to see that their safety has to be almost a required component of early journalism education,” Durkin says. “Jim was an amazing guy, and he did great work. I feel like a lot of young people are like Jim — I see future Jims walking around Marquette. I talk to the students here, and they want something positive to come out of something that was horrible. If his name and his legacy can help provide some safety for the next generation of journalists, I’m proud of that.”

Through it all, the foundation continues to look forward and seek tangible ways to measure progress. It recently undertook a qualitative analysis of the state of hostage negotiations from the perspective of affected families, publishing an 80-plus page report — no easy quest given the size of the foundation staff — that revealed substantial improvement in interactions with the government while noting a desire for additional transparent communication moving forward.

That not-there-yet mindset remains prevalent within the foundation office, as well. There’s a tangible relief each time a hostage returns home safely, but the celebration is short-lived and the focus quickly shifts back to the countless others that still remain captive.

“This is just the beginning,” Diane says. “It’s important that America sends these people out into the world — we need educators and peacemakers; we need journalists who dare to go into conflict zones. And they need to feel strongly that our government has their back.”

Reminders Everywhere

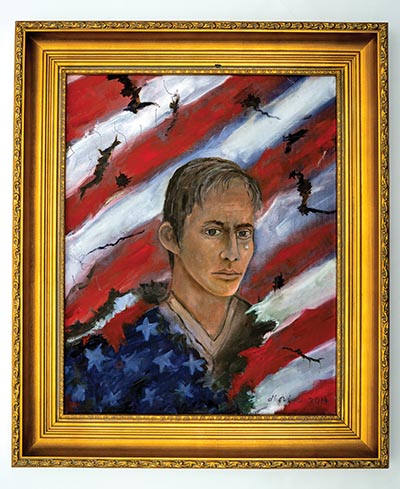

Five years have passed since Jim’s death, and even beyond the family photos that decorate their living space and the mementos displayed throughout Diane’s office, reminders of him remain everywhere for the Foleys.

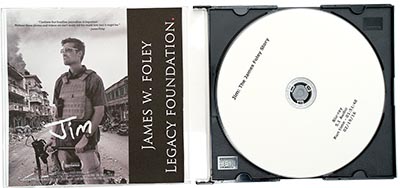

Sometimes, those can stir conflicting emotions. One of Jim’s childhood friends, Brian Oakes, directed a documentary, “Jim: The James Foley Story,” that premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2016 and won the festival’s Audience Award for U.S. Documentary, as well as the Primetime Emmy Award for Exceptional Merit in Documentary Filmmaking.

The film, which features interviews with colleagues and fellow hostages held in captivity with Jim, along with friends and family, wasn’t greeted with initial enthusiasm from Diane and John. Still shocked by his death, the Foleys were worried the film might “reclaim the horror of the image ISIS left” of their son. But Oakes instead focused on who Jim was as a person and the positive impact he had on people, even through horrific circumstances, and the Foleys have come to see the documentary as a “gift.”

There is also internal conflict as the Foleys recall Jim’s decision to return to Syria in 2012 after having been kidnapped previously. They had watched their son search in vain for a career he could fully throw his considerable passion into, and they knew he’d finally found it as a journalist. And yet they couldn’t turn off their protective parental instincts.

Diane admitted that Jim seemed “sobered” when returning home from Syria for his birthday in October 2012, but he was steadfast in his commitment to return. “I think he felt if he didn’t go back, he would be letting the Syrian people down,” John says.

But the Foleys admit they occasionally wish they had done more to encourage Jim to reconsider.

“I told him, ‘Jim, you have two master’s degrees, you’re a talented teacher and writer, you can do anything, you don’t have to go back to Syria.’ But he said, ‘Mom, I found my vocation. I found my thing,’” Diane says. “As a parent, what do you do when your kid has been struggling to find his thing? Jim was a very passionate young man, and he so wanted something he could really put his whole heart and soul into and feel like maybe he could really make a difference, and he’d found it.”

The Foleys remain fully committed to making sure he continues to make a difference. Beyond the day-to-day foundation work, Diane makes frequent appearances on television and consistently grants requests for media interviews, using Jim’s story to keep moving the needle on issues of hostage and journalist safety.

“Diane keeps Jim’s memory alive, not just with the organization but with all the interviews she does and all the advocating,” Coyne says. “It’s to make sure that nobody forgets.”

John admits there are plenty of times he’s not sure how his wife summons the strength — physically and emotionally — to continuously travel around the world and share the family’s difficult story.

But it’s never been a consideration for Diane. Though it would be impossible to ever feel completely whole again after such a shocking personal tragedy, she knows this is the only way to reclaim as much of herself as possible.

And when she does feel worn down or low on energy, she knows precisely what to lean on.

Jimmy. Jim. James. The preferred moniker doesn’t much matter at this point; it’s the power of his energy — along with “a deep faith in a loving and merciful God” — that continues to drive her.

“It was like his spirit had a life of its own,” Diane says. “It’s his spirit that has propelled everything.”

-

Written By:

Keith Testa | UNH Marketing | keith.testa@unh.edu