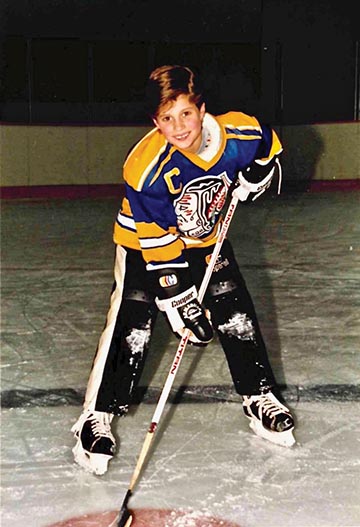

She was wearing ice skates at 18 months old, flunked out of figure skating as a toddler for being too physical and began playing hockey at the age of five, masquerading as a boy on an all-boys team.

There’s foreshadowing — and then there’s Samantha Holmes’ adolescence.

Holmes’ youth was a remark- ably precise preamble to what has been a lifetime spent as a pioneer in the quest to elevate the sport of women’s hockey. Nearly all of the elements of the future narrative were on full display: The feisty go-getter lacing them up before her second birthday and literally pushing her way into the sport she was destined to play — and change — coupled with the fitting irony that her first foray into hockey had her playing with the opposite gender.

After all, Holmes — who would later star for a UNH team that brought home the first ever national women’s ice hockey championship and was inducted as a group to the school’s hall of fame — has been fighting to ensure that women have all of the same opportunities in the sport as their male counterparts since she was a child.

“I never thought there were any barriers; I never thought there’d be an obstacle,” Holmes says. “I just thought I could do whatever I set my mind to.”

What she set her mind to, whether she knew it at the time or not, was driving societal change — at an age when most kids are still perfecting the art of tying their own shoes.

CHANGING THE GAME

As a 10-year-old girl from Mississauga, Ontario, in Canada, Holmes attended the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary, where she observed with frustration that the competition featured no women’s hockey tournament. Inspired, she began a letter-writing campaign that included correspondence to the mayor of her hometown in Mississauga, the prime minister of Canada and the president of the International Olympic Committee (IOC).

“I had two older brothers, and I remember saying to my mom, ‘they aren’t even good at hockey, and they can go to the Olympics if they try hard enough,’” says Holmes, the competitive streak that has always fueled her bubbling up in the form of sibling-directed snark. “I didn’t understand the scale of it at the time. I was just focusing on the fact that I couldn’t believe girls can’t do this, so let’s do something about it.”

Holmes found a sympathetic ear in Hazel McCallion, then the mayor of Mississauga. Not only was McCallion widely respected as a politician throughout Canada, she also happened to be a former hockey player — she played professionally in Montreal in 1940 and 1941 — and owner of the nickname “Hurricane.”

McCallion championed Holmes’ cause and encouraged her to pursue the battle, and Holmes became part of a growing chorus – one that already included McCallion and had been started and led by Fran Rider, president of the Ontario Women’s Hockey Association, who had been working in pursuit of the same goal since the 70s — that would ultimately spearhead a revolution.

“I remember getting the letter from her,” says McCallion, who at 98 is chancellor of Sheridan College in Ontario and remains as feisty as ever, having recently appeared in The Huffington Post scaling a rock wall to celebrate the opening of a rock-climbing gym in Mississauga. “She was a sweet kid, and I’m so proud of her that she would write to me at that age.”

Momentum built until the International Ice Hockey Federation sanctioned an official women’s championship beginning in 1990 — the first two of which were won by team, admittedly with her team- mates and coaches none the wiser.

The deceit was unintentional, but Holmes’ teammates didn’t realize she was a girl until there was an end-of-season sleepover and she didn’t go. “I was just Samm,” she says. “When you’re that small, you show up dressed for the rink, so nobody had any idea.”

Holmes would officially join a girls team the following year, though, and she never looked back. Hockey quickly became an all-consuming pastime — something Holmes came by naturally given the family dynamic she was raised in.

“I always loved hockey as a kid. I went to play almost every night of the week, and on Friday, when we didn’t have hockey, my dad would take me public skating,” Holmes says. “After that, we’d drop my brothers off at home and we’d go watch the Mississauga Warriors. That was my life. I didn’t know any- thing else, and I didn’t want it any other way.”

So by the time she attended the Calgary games, Holmes was already something of a seasoned veteran in the sport. Perhaps that’s why she found such supportive compatriots in McCallion and Rider, two of the most vocal proponents of the women’s game who had been fighting to promote the sport for decades.

“Things were well underway, and we had a lot of people working on it by the time Samm wrote that letter, but it brought another component because it picked up some exposure,” says Rider, who recalls fighting for a women’s championship as far back as the 1970s, using her own money to make expensive per-minute phone calls overseas to anyone who would listen in order to advance the women’s game. “I was impressed by Samm when I first saw her play. She always had a tremendous work ethic, but more importantly, she had the game in perspective. She is an incredible person who wanted to do what she could to make the game better, and she took the initiative.”

For her part, Holmes has always been quick to credit Rider, McCallion and others who were on the front lines every day for being the real drivers of change and true pioneers in the sport.

“I talk a lot about what hockey brings to kids in terms of role models, and when I look back, the timing for me to have a number of people fighting before me, it was phenomenal,” says Holmes. “I was a very small piece of the puzzle.”

BUILDING A LEGACY

Deflecting praise to her teammates is not an unusual occurrence for Holmes, who quickly grew to become recognized as an outstanding player and better captain on the ice. That also put her in pretty high demand as high school and then college approached. She chose UNH in large part because it was one of the most prominent women’s programs in the country, and the recently opened Whittemore Center was “one of the best facilities in college hockey at the time,” Holmes says.

The appeal was understandable. UNH was one of the first premier collegiate women’s hockey pro- grams in the United States, going undefeated in 15 games during its inaugural season in 1977-78 while outscoring the opposition 120-32, and playing 74 games — over four- plus seasons — before suffering its first loss.

Eleven schools across the country had varsity programs in the early 1980s, and the Wildcats remained one of the most dominant, winning six women’s intercollegiate championships in an eight-year span to begin the decade. Holmes arrived in Durham as more schools were developing programs and played a part in adding to the school’s legacy, helping the Wildcats lock up the inaugural American Women’s College Hockey Alliance national championship with a 4-1 victory over Brown University in Boston in March 1998.

More than two decades after skating off the Whittemore Center ice for the final time, Holmes still describes the support of UNH, and the athletic department in particular, throughout her career as exceptional — especially in terms of scholarship opportunities, which were hard to come by at the time for international female hockey players.

“UNH was ahead of its time with the development of women’s hockey, and I am ridiculously fortunate to have gone there,” Holmes says. “Had it not been for the environment we had at UNH and the support athletically and academically that my teammates and I received, I don’t know if I would have moved on to flourish chasing my bigger dreams.”

FAMILY TIES

That support extended well outside the rink, too. It was while attending UNH that Holmes met Emeritus Professor of kinesiology Steve Hardy, with whom she immediately forged a bond that has led to a fulfilling lifelong friendship.

“I can’t really even talk about Dr. Hardy without tearing up. He was like my dad away from home,” says Holmes, the emotion clear in her voice as she recalls the many dinners Hardy and his wife, Donna, would host for international women’s hockey players who couldn’t make it home during holiday breaks. “He is just such an amazing person — he and Donna are so giving, kind and supportive. They are just phenomenal people.”

What Holmes may not have known at the time was how reciprocal the impact of their relationship was. Years earlier the Hardys had endured the loss of their oldest son, Josh, who passed away after a battle with brain cancer, and interacting with student-athletes injected a lively, youthful energy and spirit into their home that had something of a life-changing effect.

"To me, those are the most powerful parts of being a professor. We had lost a son by that time, and when you lose a child, it puts a lot of things into different perspective,” says Hardy. “For me, the students at UNH really saved me professionally after Josh died, so this was just one little way to give back. Some of them have become like daughters to us. We call them our UNH hockey daughters.”

Hardy recognized immediately that Holmes was destined for big things beyond UNH, in the sport of hockey and otherwise. The same dogged determination that prompted the 10-year-old Holmes to take game-changing action was evident from the start, as was a genuine caring demeanor that endeared her to most everyone, Hardy says.

“She’s a force. Some people have that, and some people don’t. I have to think that’s in your DNA to some extent, to be competitive like that,” says Hardy. “She’s a wonderful competitor, but just as importantly, she has such a big heart. That’s what makes her so special to me.”

It is through the wake of another devastating family tragedy that Hardy perhaps best articulates how both of those qualities are always on full display in Holmes. The youngest of Hardy’s three sons, Nate, was killed in action as a Navy SEAL in Iraq in 2008. While at UNH, Holmes crossed paths with Nate a few times when he was in high school or home on leave, and the two continued to communicate often over the years.

Last spring, Holmes was planning a trip to Washington, D.C., for a work conference, and told Hardy she was going to visit Nate’s gravesite. Hardy, in turn, sent Holmes a map with a red dot noting the location.

Holmes, though, forgot the map when visiting — and still managed not only to enter Arlington National Cemetery after it was closed for the day but also to coerce a nearby general into driving her directly to Nate’s gravesite.

To Hardy, that sums Holmes up perfectly: compassionate enough to make the visit on her own time during a work trip and tenacious enough to make it happen regardless of the roadblocks.

“I get a text one afternoon, and she tells me she forgot her map. So I call her and say, ‘What am I going to do with you?’ And she says, ‘What do you mean what are you going to do with me? I just talked my way into Arlington National Cemetery after it’s closed,’” Hardy recalls. “Unless you have a pass or you’re part of a Gold Star family, you can’t drive in there, and not only did she talk herself into the closed cemetery, she ended up getting a ride in.”

UNFINISHED BUSINESS

Aside from the lifelong relationships she forged and the success she and her teammates experienced on the ice at UNH, one of Holmes’ other cherished experiences from that era was the opportunity to compete as a Wildcat against the United States women’s national hockey team, which came through for a showdown during her sophomore or junior season. UNH lost in a rout — Holmes said she can’t recall the final score, but she can remember that she scored both of UNH’s goals in the game.

“I remember thinking, ‘Go Canada!’” quips Holmes.

Shortly after leaving UNH, Holmes was able to repeat that refrain in earnest — and fulfill one of her lifelong dreams — by officially suiting up for the Canadian women’s national team. Though she would never appear in a world championship or the Olympics with Team Canada, the opportunity to compete at that level for her nation was a career highlight.

“I think being Canadian and the passion we have in this country for hockey, I was very, very fortunate to be involved in the Canadian program,” says Holmes. “Just to experience that level of hockey, it was what I always dreamed of as a little girl. I wanted to play hockey for the rest of my life.”

Despite eventually receiving her walking papers from the Canadian national team, Holmes wasn’t ready to walk away from the sport for good, so she sought out additional opportunities — and continued to actively create them for others, despite encountering a neverending string of challenges that most men’s teams avoided, such as lack of sponsorships and funding issues.

She went on to play professionally in several leagues in Canada and was instrumental in the formation of teams in two different women’s leagues — acting as founder, player, coach, general manager and all- around gofer for one of them, the Strathmore Rockies of the Western Women’s Hockey League.

Holmes built the team from the ground up and was responsible for everything from recruiting players to securing sponsors to turning the lights on in the rink, all while playing and “sometimes” coaching. And she did it all, once again, to provide other women a place to pursue their hockey dreams.

“There were so many of us that still wanted to play competitively, and I thought, ‘this needs to be done, so let’s do it,’” Holmes says. “I said ‘let’s raise some money and find some ice and find a coach and get into the league.’”

In 2011 Holmes was also heavily involved in the foundation of Team Alberta in the Canadian Women’s Hockey League (CWHL). She would later serve in a consulting role for Team Alberta and also held a role in operations and sponsorships for the CWHL. For all of that, she was ultimately the first-ever recipient of the CWHL Hockey Humanitarian Award in 2013.

Holmes’ days of playing professionally are behind her now — though she does still play pickup games regularly — but she has never viewed her work in the game as complete. She still sees women’s hockey leagues struggle for sponsorship dollars and exposure and is hopeful that one day the National Hockey League will establish a relationship with the women’s game in much the same way the NBA has with the WNBA, bringing the clout and power that comes with such a partnership.

“That’s where I’d like to see women’s hockey go, so there’s more chances for girls and women to achieve that high level of success,” Holmes says. “We’re almost there.”

Through it all, Holmes continues to deflect credit, despite a wake of accomplishments that has seemed to follow her since she was in grade school.

“I don’t think of it as a legacy,” Holmes says of her impact on the game. “There’s been a lot of change in women’s hockey, and the game has given me so much, so I continue to try to see what I can give back. To me, it’s paying it forward.”

Her path to paying it forward may soon revolve around her daughters, who at six and four are just beginning to explore the sport that has been at the center of their mother’s life for decades (her oldest is already playing). Holmes says she’s already jokingly asked her mother if she was like this at her daughter’s age — the answer was a resounding yes — but she’s excited to watch them experience the sport however they decide to.

Hardy, for one, wouldn’t bet on her impact being limited to only her own children, though.

“She has that fire in her belly, and now she’s got two little girls — that’s going to be light’s out for youth hockey,” muses Hardy. “They’re not going to know what hit them.”

-

Written By:

Keith Testa | UNH Marketing | keith.testa@unh.edu