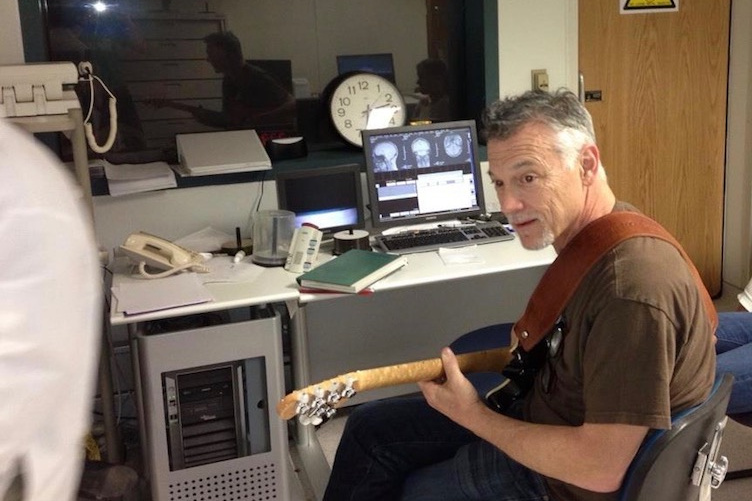

Professor Don Robin plays his guitar while musician Anne Drummond undergoes a brain scan. The image on the computer screen in the background is of Drummond's brain activity during the session. (Courtesy photo)

Musical improvisation and neuroscience aren’t terms you often hear coupled in the same sentence. Ditto for neuroscience and kindergarteners, or older elementary school students, for that matter, unless you’re Donald Robin, professor and chair of the communication sciences and disorders department in the College of Health and Human Services.

Robin came to UNH about 18 months ago, bringing with him work he had done previously that involved scanning the brains of Grammy award-winning jazz musicians while they improvised on a specially designed keyboard to see what parts of their brains “turned on,” how those regions talked to each other and what parts didn’t respond.

"So, the question becomes, can music change your brain?”

“What you see is that the brain is really active, and you get to see that in areas of the brain that regulate language, memory and emotions. You see what it’s doing at rest, too,” Robin says. “So, the question becomes, can music change your brain?”

Robin’s brain-music research, which he began while a professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio, focuses on the relationship between music and learning. During the 2017 fall semester, he assembled a team that included UNH communication sciences and disorders, music and neuroscience majors and took his science to the Seacoast Charter School in Dover, New Hampshire. Sara Willis ’18 helped him plan the program that was piloted with kindergarteners.

“We focused on what the kids could learn about their brain in terms of how it helps them function in their everyday life,” says Willis, a communication sciences and disorders major. “We taught them the different jobs that each lobe does — for example, the frontal lobe helps us think, the occipital lobe is how we see, the temporal lobe is for hearing and the parietal lobe for touch.”

Foam forms colored by students to reflect various parts of the brain. (Courtesy photo)

Using an assortment of techniques that involved listening to and making their own music, the elementary schoolers learned what musical improvisation does to the brain, how it makes certain parts of it light up and why some areas stay dark. The children were each given a Styrofoam head like those used to display wigs and told where each lobe is located. They were then asked to draw pictures on the foam form of what they thought their brains were doing as they made sounds on a keyboard.

Robin, who is a jazz musician, and professional flutist and composer Anne Drummond, with whom he has collaborated in the past, played for the students. Told to close their eyes while they listened, the kindergarteners were later asked to describe what they’d felt — not heard, felt. Then they discussed the lobe responsible for those feelings, and the colors they had seen while listening to Robin and Drummond play.

“It’s putting language in music,” Robin says. “And it’s teaching them that different parts of their brain are doing different things at the same time. They’re learning how the brain processes music.”

The research is helping Robin and others understand how studying musical improvisation and the brain can enhance learning of cognition, language and motor control as well as its influence on creativity and imagination. The ideal, Robin says, would be for the students to undergo brain scans while listening to music so researchers could see how the brain changes with learning and how those changes are associated with the creative process.

For now, Robin and a new team of UNH students in the neurosciences are working with third and fourth graders at the charter school, whose focus is on teaching education through the arts. Willis is leading the team.

“It’s important for children to learn about their brains because it helps them take better control of their learning and actions,” Willis says. “I learned just as much if not more than the students did.”

The next phase of Robin’s research will explore neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to organize through new neuron connections, and to study how learning music and neuroscience can help brain-injured individuals. “The amazing thing is that you can make neural connections stronger within a week or two,” says Robin, assistant director of the CHHS laboratory of speech and language neuroscience. “Our prediction is that these changes are permanent and provide evidence to support the inclusion of music, art and neuroscience in school programs.”

Interested in studying communications sciences and disorders? Check out the UNH College of Health and Human Services.

-

Written By:

Jody Record ’95 | Communications and Public Affairs | jody.record@unh.edu