THE SPITE FENCE: In this mural painted in 1954 by the late UNH art professor John Hatch, now hanging in the Durham Community Church, the Durham waterfront of the 1820s fairly bustles. A fence built by Ben Thompson's father forced neighboring shopkeeper Ebenezer Smith to walk the long way around

It goes without saying that he was a man of marked peculiarities," declared the Rev. S.H. Barnum at Benjamin Thompson's funeral in January of 1890, "and they were of such a nature as to be easily observed." Thompson's relatives and Durham townspeople must have nodded in recognition, remembering the familiar sight of the miserly old man, wrapped in his shawl, riding around town on horseback. But there was another peculiarity, far less observable, that would become a source of considerable outrage and controversy once his will was read several days later.

Even today, 200 years after he was born on April 22, 1806, Benjamin Thompson remains something of an enigmatic figure. UNH historian Donald Babcock once described him as an "essential American," influenced by the intellectual movements of his era and motivated by quintessentially American values. But diaries, letters, and oral histories from the period reveal other, more personal, influences and motivations that may help explain why he did what he did—and kept it a secret for 34 years.

A photograph, upper left, shows Ben Thompson's

house. Located where the Durham post office

now stands, it burned in 1897.

Benjamin Thompson was the fifth of six sons, and not only his father's namesake but also, reportedly, his favorite. He strongly resembled his grandfather Judge Ebenezer Thompson, a renowned patriot. In December 1774, the judge was one of a group of men who stole ammunition and weapons out from under the British at Fort William and Mary in New Castle, brought them back to Durham by gundalow, and hid them under the pulpit in the meetinghouse. Judge Thompson went on to become the first secretary of state in New Hampshire and a presidential elector for both George Washington and John Adams, among numerous other public positions.

As he grew older, Benjamin not only looked like his grandfather, he shared many of the same traits: a love of reading, a distaste for extravagance of any kind and a weak constitution. On his mother's side, he was descended from great-grandfather Thomas Pickering, known as "Penny Tom" for his fondness of the adage "a penny saved is a penny earned." Benjamin's mother, wrote grandnephew and local historian Lucien Thompson, was an industrious woman who was often heard to say, "I hate lazy people!"

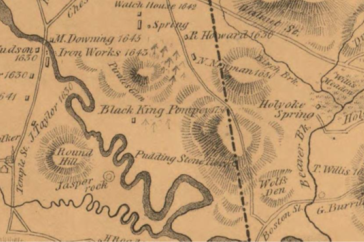

Thompson came of age in the 1820s, when Durham was a small but thriving village of 1,200 at the crossroads between the stagecoach route from Boston and the state's first turnpike, now Route 4. The town center was perched on the bank of the Oyster River, near a gristmill, a sawmill and two boat-building "ways." Between 1776 and 1829, 75 ocean-going ships were built in Durham, including two privateers for the War of 1812.

Many residents were farmers, and John E. Thompson (no relation), in his remembrances of the period, expressed sympathy for tenants who farmed "to the halves," splitting crops with their landlords. He estimated that fully three-fifths of the town's land was thus farmed. Benjamin Thompson's father was the landlord of at least two of these farms and also owned one of the 13 stores in Durham at the time.

According to John Thompson, many of these stores sold little but salt fish, rum and molasses; yet "they afforded good idling places for men of small means to drop in and crack jokes, sing rude songs, drink rum, and go home at night. . . gloriously drunk." Villagers socialized at huskings, quiltings and annual muster. At purely social gatherings, young people enjoyed popping corn and toasting seeds on a hot shovel for "marriage signs."

Whether or not he ever tried to divine his marital prospects in toasted seeds, the young Benjamin Thompson apparently was looking to marry. At 20, he courted Sophia Haven of Portsmouth and even proposed to her, only to learn that she had just become betrothed to another.

After receiving his education at a village school and Durham Academy, Thompson served briefly in the state militia and taught school for at least one winter. In 1828, when his father offered to give him one of his farms, known as the Warner Farm, and two other tracts of land, Benjamin agreed to accept this gift—but only if he could receive the deed right away. He had observed what happened to the widow of an older brother who died without the deed to land their father had given him.

Thus Thompson, shrewd at the age of 22, assured his ownership of the land he would farm for the next 60 years. Having learned bookkeeping in his father's store, he began a lifelong habit of keeping account books. From 1828 till 1889, a year before he died, he filled ledgers with hundreds of pages of detailed records.

That same year, Benjamin's niece, Mary Pickering Thompson, began going to school—at the age of 3. Education at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary became her ticket out of Durham, which she later called "that prehistoric place." In addition to some modest investments, she would make her living by writing, publishing more than 130 articles. Mary also wrote hundreds of pages of letters and diary entries devoted to her passions—literature, art, religion, and, ultimately, the envy of her uncle's wealth.

In 1841, the Boston & Maine Railroad came to Durham, and the Boston to Portland stage line ceased running. The coming of the railroad represented just one of a series of profound changes. The national shift from an agrarian to industrial economy had begun, as well as a migration from stony New England to the rich farmlands of the Midwest. In Durham, the town center even moved west slightly, to its present location, toward the railroad and away from the river, which would become less and less important.

Thompson sold a right of way to the B&M Railroad through his farm, running through the location of DeMerritt Hall and up what is now Edgewood Road. This was the first time he would make money from the railroad, but not the last.

HORSE SENSE: Ben Thompson's one-horse chaise,

above, was used for many years in UNH class

reunions, here for the Class of 1887.

True to his utilitarian and frugal values, Thompson worked hard at farming, but he also worked smart. He was the first to grow the Baldwin apple in Durham, budding and grafting his own trees, and was considered a pioneer in raising fruit for the Boston market. His farm produced hay, lumber, butter, cheese, vinegar, cider, meat, and grain. He seemed to record every penny in his account books, noting the price of a bushel of potatoes (25 cents), as well as the reason for a worker's absence ("wife sick" or "day fishing"). He provided his hired hands with meals, tobacco, rum and clothing. He watched over the operations with a keen eye, shouting "get every bit!" if he spied a worker trying to pass over a bee-infested forkful of hay.

After his father died in 1838, Thompson lived with his mother for two years and then announced he was taking a trip to Cuba. His mother moved in with her daughter and son-in-law, but "Uncle Ben," Mary Pickering Thompson later wrote, "never went to Cuba after all. It was only one of his sudden freaks that he never carried out." He moved back into the family home by himself and hired a housekeeper. A few years later, Lucetta Mary Davis, on vacation from her job in New York City's Astor Place, agreed to fill in for the housekeeper for two weeks. She ended up stayed for more than 40 years, acting as Thompson's housekeeper, nurse and confidential secretary until he died, in 1890, in the same house where he had been born.

When Thompson was 44, he learned that the object of his youthful desires, Sophia Haven Appleton, now the mother of three, had recently been widowed. A romance was rekindled, an engagement secured, and then Thompson gave his fiancée $1,000—more than $22,000 in today's dollars—to buy new furnishings for his house, located at the corner of Madbury Road and Main Street.

What happened next is a matter of some conjecture, since historical accounts differ. Niece Mary later wrote simply: "He jilted her without assigning any reason." In another version, Thompson affronts his betrothed by moving all her fancy Boston-bought furniture into the barn. In a 1932 book called New Hampshire Folk Tales, he comes home to find a fashionably flimsy chair, flies into a rage, and kicks it across the room, shouting, "[That's] the most hideous impractical, uncomfortable looking pile of sticks I ever saw hitched together!"

Also a matter of conjecture is whether the broken engagement had anything to do with something that happened six years later. That's when Thompson wrote his will, a document that not only gave the last 34 years of his life a higher purpose but also gave the state of New Hampshire a gift, a command and a blueprint. He had decided to bequeath virtually his entire estate to the state for the purpose of establishing an agricultural college, provided the college was located on his farm in Durham. In the original will and subsequent codicils, he stipulated what might be taught at the college and made other "suggestions," including the idea that students be required to say prayers and "labor on the land" every day.

Thompson also urged the state of New Hampshire to apply to Congress for a grant of land to help support the college. Given that the will was written in 1856—one year before Rep. Justin Morrill of Vermont proposed the land-grant act and six years before it was signed by Abraham Lincoln—Thompson's bequest seems rather bold and visionary. The act made each state eligible to receive public lands to be sold for the purpose of funding a state college devoted to teaching agriculture and mechanical arts. Ironically, the money from these sales could be used for just about anything except purchasing land. Thus Thompson was one of the first in a wave of farmers to donate the land for a land-grant college to sit upon.

Up until this point, both public and private colleges in the United States had largely followed the European tradition of educating upper-class young men for the clergy or the professions. In the mid-1800s there was a growing national movement to incorporate science into the curriculum and open access to "the industrial classes." Even spiritual leaders like Boston's most prominent minister, William Ellery Channing, preached the gospel of agricultural education. Thompson clearly had been following the national debate, reading political tracts in his armchair, and forming his own opinions.

At the time when he wrote his will, Thompson was clear about his goals, if somewhat short on money. Over the next 34 years, he quietly became richer and richer, and at the time of his death, his estate was valued at approximately $400,000, about $8 million today. He also, for the most part, kept quiet about his intentions. He did correspond with the New Hampshire-born head of the National Agriculture Society, Marshall Wilder, who had founded MIT and the Massachusetts Agricultural College (now UMass). Housekeeper Lucetta Davis, acting as his secretary, certainly knew, as well as the executors of his will. But he stood quietly by as New Hampshire founded its first land-grant college in Hanover "in connection with" Dartmouth College in 1866—a connection that became increasingly uneasy—and as the people in his own town came increasingly to look upon him as a miser.

We will never know for certain how the presence of a wife and three stepchildren might have affected Thompson's ability to amass a fortune over the second half of his life, not to mention his desire to dedicate that fortune almost entirely to the goal of bringing science to farming and bringing farmers to college. At convocations and other ceremonies, UNH historians have naturally overlooked the love story and focused on the ideas and political movements that may have inspired him. Nevertheless, local storytellers have connected the dots without hesitation: Love was lost and supplanted by a lifelong, largely secret devotion to the advancement of agricultural education, which Thompson linked in his will to the promotion of "the happiness of man, the honor of God, and the love of Christ."

Although Thompson has mainly been remembered as a farmer who donated his farm to the university, it was as an investor, primarily in the railroad system, that he made his fortune. He began with a $6,000 inheritance from his parents, and at his death the two most valuable components of his bequest were railroad stocks and railroad bonds. "Thus while he rarely left Durham," wrote UNH history professor Philip Marston, "he nevertheless participated in the expansion of the United States."

As long as his health allowed, he also went to the railroad station on horseback every day—tall, spare, wrapped in his shawl—to watch the train come in. At the station, he would often place five pennies on the ground and cover them up by scuffing the dirt with his shoe. Then he made a proposal to any small boys who were around: They could keep the pennies, but only if they uncovered every one. When he caught small boys misbehaving, on the other hand, Thompson might threaten to haul them off to the Dover jail. In fact, the Rev. Barnum ruefully acknowledged in his eulogy that some people in town enjoyed provoking Thompson, who was known for his "explosive temper and profane habit."

It wasn't just on the 5-cent level that Thompson liked to use his gifts as a kind of challenge grant. He offered to donate $100 to the town library, but only if the citizens contributed $400. For many years he donated his entire hay crop to the library association, as long as the association took responsibility for cutting, pressing and shipping the hay. And when a man was killed in a railroad accident, Thompson donated his apple crop to the man's family, provided the railroad company would ship the crop to market for them.

Rev. Barnum dryly described Thompson's "benefactions" as "perhaps not large compared with his wealth" and also suggested that envy of his wealth contributed to ill feeling toward him around town. While Thompson was growing wealthier and wealthier, the town was losing industry and commerce, and by 1860, its population started to dwindle. Niece Mary, who lived diagonally across the street from Thompson, took his lack of generosity very personally.

In the late 1870s, as she reached the half-century mark, Mary spent four years traveling around Europe, and recounted the joys of European art and culture in letters to her niece and sister-in-law. The letters were peppered with exclamations like "O for a mint of money!" or "Oh, for some of Uncle Ben's money to enable me to stay another year!" Ironically, not only did she stay another two years without a penny from Uncle Ben, she also managed to experience all the wonders of Europe on a tight budget, even if it meant scaling the cone of Mt. Vesuvius on foot while a wealthy woman was carried up in a chair.

The revelation of the contents of Benjamin Thompson's will in February 1890, caused something of an uproar, and not just among his heirs, some of whom promptly took their grievance to court. The state had two years to decide whether to accept the gift with all its stipulations, including the requirement to build an agricultural college on Thompson's farm; to appropriate $3,000 every year for 20 years to support that college; and to guarantee 4 percent compound interest on those appropriations as well as the estate. Otherwise, no bequest. Instead it would be offered to Massachusetts, and if that state turned it down, to Michigan. He did leave his housekeeper 20 shares of bank stock and all his household furnishings and belongings, valued at $1,000.

Newspapers had an editorial field day with the proposal, referring to the college as an "incubus in the shape of a state agricultural college," a "turnip yard," and something about as useful as a "million-dollar pest house." The Daily Press of Manchester declared that the agricultural college "fad" was "pretty well played out." Thompson proved more prescient, envisioning in his will that such colleges would "be multiplied in every state of this great confederacy."

A year after his death, the agriculture committee in the state legislature finally took up the matter on Feb. 21, 1891. The heirs, led by Ben's nephew William Thompson from Ohio and presumably including Mary, were no longer contesting the will on the grounds of "mental disabilities," a newspaper reported, but were still pressing an appeal claiming the state had no legal right to accept the gift. (The case was ultimately dismissed.) On this same day, as if on cue from central casting, a cousin swept in from the Midwest. James F. Joy, a railroad magnate living in Michigan and the executor of Thompson's will, had grown up with Thompson. Where Thompson had been contented to speak only through his will, Joy was now able to answer some nagging questions.

"My heirs are pretty well off," Thompson had explained, said Joy, and "he formed an idea that the best use he could make of his fortune was to put it into an agricultural college for the education of the boys of the state. . . To the day of his death this idea was uppermost in his mind." Joy urged the committee to move the struggling New Hampshire College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts from Dartmouth to Durham immediately.

Alice Stevens' 1935 portrait of Ben Thompson,

based on a photo, hangs in Thompson Hall.

The committee voted unanimously to accept the bequest, and within a year, Thompson Hall was under construction on the new campus. Mary never carried out her threat, in a letter to her niece, to move to the Dark Continent should the state accept the bequest. But she was still angry enough in 1892, two years before she died, to write, "I will do nothing whatever to countenance my perverted uncle's alienating the property of my grandfather for such a purpose as this college." Perhaps she would have been mollified if she had lived to see what land-grant colleges like UNH would do for the education of women.

Many have speculated as to why Ben Thompson kept quiet about his grand plans all those years. Did he fear the wrath of the disinherited heirs—or even relish the thought of revenge? Or was he simply shy and modest about receiving attention for giving such a large gift?

For a clue, we might look to Benjamin Thompson's most peculiar peculiarity. In 1968, Lucetta Davis's grandniece appeared at UNH, bearing a nondescript, brown plaid blanket with fringe, reputed to be The Shawl, the constant companion of his later years. It had come in handy in church, where he sometimes snoozed through a sermon, smothered in his shawl, right up front in pew #34—a citizen of the first rank in little Durham, shy, yet fearless of what others thought of him in life or death. And so it was that he was willing to appear small minded, while secretly devoting his life and fortune to the betterment of generations of young people he would never meet. One can even imagine that he took some pleasure in this paradox. And maybe, just maybe, he had a fondness for surprise endings.