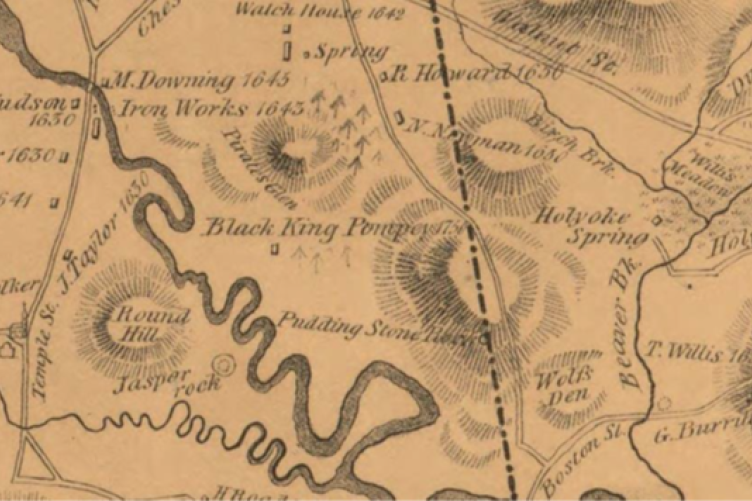

Figure 1. Detail of Lewis map showing Black King Pompey’s house, the hill just above his house is Vinegar Hill (town property today). From The History of Lynn by Alonzo Lewis. Press of J. H. Eastburn, 1829, Lynn (Mass.).

Each year, The New England Humanities Consortium (NEHC), a network of universities and colleges dedicated to intellectual collaboration and regional programming, puts out a call to member institutions for projects that bring faculty and students together across campuses to do meaningful work. This year, when she saw the call, UNH Professor of Anthropology and Director of the Center for the Humanities Meghan Howey texted her friend and former colleague, Kabria Baumgartner, now at Northeastern University, and said, “Let’s go find Pompey.”

Their new collaborative project feeds into a growing stream of research, engagement and community organizing that is reckoning with the once-overlooked realities of New England’s history, including the very real presence, and prevalence, of enslaved Africans. In reshaping the commemorative landscape of the region, Howey and Baumgartner will focus on the story of King Pompey, an enslaved African who was later manumitted and became one of the first Black property owners in colonial New England.

King Pompey is portrayed in accounts of the time as an esteemed leader who hosted enslaved and free Blacks from far and wide on his property, situated in Lynn, Massachusetts, close to Vinegar Hill on the Saugus River. The public record of a deed to Pompey Mansfield for two acres seems to confirm the basis for this remembrance. At a stone house he had built on that land, Pompey and his wife, Phillis, are reported to have welcomed celebrants for Black Election Day, an annual west African-influenced cultural festival. The highlight of the day was voting for and crowning a king, who might later be called on to settle disputes and offer insights on matters important to the Black community. Similar celebrations took place in towns and cities throughout colonial New England.

Howey has long been using archaeology to reconsider and expand the story of colonial New England and has collaborated extensively with Indigenous knowledge-keepers and, more recently, the Black Heritage Trail of New Hampshire to generate new areas of research. She started the Great Bay Archaeological Survey (GBAS), an interdisciplinary and community-based archaeological survey for early colonial sites, in 2016 and last summer ran an NEH-funded summer institute for teachers based on the work of GBAS and focused on bringing the dynamic interactions of people in colonized New England into focus for 72 K–12 educators from across the country.

While the story of King Pompey continued to circulate through the early decades of the 20th century, the location of his land and home has been buried and his story obscured. With their funding from NEHC, Howey and Baumgartner will conduct background archival research on King Pompey and his property, scrutinizing unconfirmed historical details to better pin down this story. They will also compare georectified maps with contemporary LIDAR-derived digital topographic maps to identify historically referenced landmarks and narrow in on areas that may have the potential for the recovery of intact cultural features via subsurface survey.

Howey will supervise one or two undergraduate students from UNH to conduct geospatial analyses of archival work and LIDAR/land data and will lead the fieldwork (systematic shovel-testing). Baumgartner will supervise one to two history students from Northeastern in background archival research, which will be done in collaboration with a community partner, Emily Murphy, historian and curator at the National Park Service’s Salem Maritime and Saugus Iron Works, who commented on the collaboration: "We are so pleased to see this work building on the scholarship in African Americans in Essex County: An Annotated Guide by Dr. Kabria Baumgartner and Dr. Elizabeth Duclos-Orsello that we recently published. The story of King Pompey is only one of many overlooked stories in Saugus, including those of Native Americans, the Scottish prisoners of war and other enslaved and free African Americans, that we are excited to explore further with the help of partners."

The team will host a summit at UNH in May, featuring students from both UNH and Northeastern, who will co-develop the archaeological fieldwork plans for summer 2024. Curation of recovered artifacts will be completed in fall 2024.

Howey is also no stranger to setting off on what may seem like long-shot searches that prove to be serendipitous. In the summer of 2020, when the season was reduced to just her and one assistant, she decided she would go looking for a site that GBAS’s long-term Indigenous collaborators, Paul and Denise Pouliot, the head speakers of the Cowasuck Band of Pennacook Abenaki peoples, had told her was out there. They pointed to a large field to the east of a colonial homestead GBAS had been excavating and said look for an Indigenous site out there. Finally, Howey, despite some skepticism, listened. She and her assistant spent nine weeks surveying that field, full of ticks and poison ivy, with no luck. Just as they were about to close the 10-week season, one of their very last test pits revealed what turned out to be a large hearth. Subsequent seasons of GBAS excavations have shown that the hearth was part of a large Indigenous village with horticultural fields dating from 1200 AD through the end of the 17th century — exactly as her Indigenous collaborators had told her. Howey remembers this as both one of the greatest finds of her career and a humbling but critical lesson that, if we really want to tell different stories about our past, we have to genuinely listen to diverse sources of knowledge and information. That is exactly the aim of this new project.

Baumgartner is dean’s associate professor of history and Africana studies and associate director of public history at Northeastern University and was an associate professor in American Studies at UNH prior to joining Northeastern. Her first award-winning book, In Pursuit of Knowledge: Black Women and Educational Activism in Antebellum America, tells the story of Black girls and women who fought for their educational rights in the nineteenth-century United States. She is completing her second book, Separate But Equal: The Origins of American Educational Policy, which explores Black youth activism and civil rights in nineteenth-century Boston.

Baumgartner says of what drew her to this project: "I've been fascinated by early Black history for a while — specifically, the experiences of Black people in New England. Oftentimes what I'm reading about early Black experiences focuses on slavery and oppression. That makes sense, of course, given the history. I've often wondered about those fleeting private and intimate moments outside of the watchful eye of an enslaver when Black people could be themselves, enjoy themselves and each other, and be in community. I found that I could access parts of that story through Black Election Day celebrations.”

The team says they understand that they may not find conclusive material evidence of King Pompey’s home or its artifacts, but even conducting the project will be a step toward reclaiming and asserting the significance of the Black lived experience — of joy and celebration — in colonial New England. Their hope is later to work with the National Park Service to erect a historical marker about King Pompey and do more outreach and exhibits that share the story and the figures of Black Election Day.

-

Written By:

Katie Umans | UNH Center for the Humanities | katie.umans@unh.edu | 603-862-4356