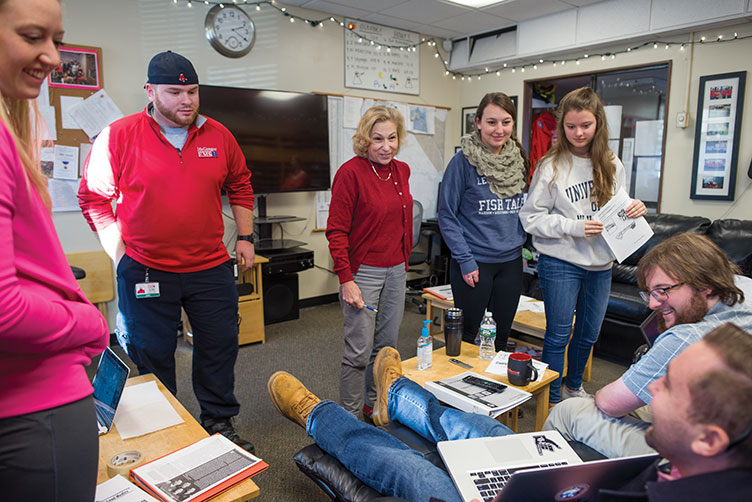

It’s a Friday afternoon, and eight UNH students are gathered in the dayroom of the McGregor Memorial Emergency Medical Service (EMS) for what, for most of them at least, will be their last class of the day: Biomedical Science 635, taught by Mary Katherine Lockwood. Arrayed across a neat U of black sofas and office chairs, dressed in jeans and sweatshirts or McGregor-issued navy pants and red polo shirts, the students take turns sharing stories of recent patient calls, their words occasionally interrupted by a two-tone note from the overhead speakers signaling an incoming dispatch from 911.

A female student leans forward as she describes a trip to a downtown parking lot to assess a man about her age who appeared to have had a seizure or maybe a stroke. The male student next to her follows with a story about a recent call to a nearby walk-in clinic to transport an older woman to the emergency room. She was a picker, he explains; covered with sores from where she’d tried to dig out the thorns she thought were still embedded in her skin after falling into a thorn bush five years earlier; she’d even had a small plastic container of scabs and skin fragments that she’d showed him as “proof.”

“I wasn’t completely sure how to play it, you know?” he asks. ”On the one hand, I didn’t want to play into her delusions. But she was clearly agitated, and so I didn’t want to do anything that would upset her more.”

Across the circle from him, another female student chimes in. She’d recently been on scene at a minor one-car accident involving a teenager who had driven off a road and hit a tree. “He had a different explanation for what happened, but I think he was probably texting and driving,” she says. “We’d taken his phone away so we could run a concussion protocol on him, but in the course of, like, five minutes he must have asked us for it 15 times: ‘Can I have my phone? When can I have my phone back? You can’t hold my phone against my will.’”

Lockwood’s been jotting notes as her students talk, but now she sets down her pen and raises her eyebrows. “He’s addicted to his phone,” she says.

Around the circle, heads nod in agreement — these are college students, after all; who among them doesn’t know someone who’s obsessed with taking selfies or Instagramming every trip to Breaking New Grounds? — but Lockwood says she means that literally. “There have been studies on this,” she says. “You know the little ding when you get a new text or Snapchat or someone comments on your Facebook post? It creates a little burst of dopamine, the same as what you get from drugs or alcohol. This is possibly a person who’s physiologically addicted to his smartphone.”

The class continues on in the same vein — a mix of group therapy-type shares and Lockwood’s clinical explanations and contextualizations for aspects of virtually every call — until the overhead speaker sounds again. This time, the subject is an older female on Durham Point Road. She’s been running a fever for five days; she’s conscious but not responsive; the dispatcher rates the emergency level at delta, which means multiple units and immediate response. It’s a McGregor call for sure, and two of Lockwood’s students leap up to join a paramedic and an advanced emergency medical technician (AEMT) already out in the ambulance bay ready to head out: They’re nationally registered EMTs too, and they’re here to work.

As they leave, Lockwood explains that that’s the name of the game for the students in her pre-hospital preceptorial, a combination of seminar and experiential learning that’s like nothing else at UNH. “There’s hands on,” she says, “and then there’s this.”

Rock Stars

Tucked away in a low brick building on College Road that once housed the university’s lawnmowers and a vacuum cleaner repair shop, McGregor Memorial EMS provides one of the only community/university ambulance services in the country, staffed primarily by volunteers. It’s the emergency 911 ambulance service for Durham, Lee, Madbury and UNH, with 75-odd volunteers who make some 2,250 emergency calls per year, responding to needs that range from broken bones to cardiac arrests to major vehicle traumas. And while not all of the service’s EMTs are students, roughly 75–80 percent are. For the majority of those student caregivers, the experience is the first step to a career in the healthcare field.

“People will say to me, ‘Well, but you’d never have just UNH students out there running calls, would you?’ I tell them, ‘Of course we do. We do that all the time.’”

Ben Claxton ’14 became involved with McGregor between his sophomore and junior years at UNH. The son of a Penn State physician and cancer researcher, he’d come to Durham with his sights set on medical school, but McGregor offered a key real-world complement to his classwork and research in professor Charles Walker’s lab. Now in his second year at Penn State’s Hershey College of Medicine, Claxton says the patient care experience he gained putting in upwards of 100 hours a month at McGregor was invaluable.

“For many of my peers, the first time they have to talk to a patient is when they’re in med school,” he explains, “and the anxiety and unfamiliarity that surrounds that experience just makes your mind go blank. Maybe they job-shadowed a doctor or worked as a medical scribe, but at McGregor, we were taking care of real patients, in real houses, needing real care. Having that opportunity to practice direct patient care provides a critical leg up when you’re going into a career in medicine.”

Like most UNH student EMTs, Claxton’s involvement with McGregor began with taking (and passing) a national-standard 110-hour EMT course as well as New Hampshire-specific written and practical examinations. Once they obtain their national registry, potential McGregor EMTs then complete a 30-to-90-day probationary period that includes 40 hours of observation, a mandatory “probie” weekend and additional practical skills modules tailored to McGregor needs. They also learn how to drive the service’s three ambulances and master the high-tech equipment they contain inside and out.

“People will say to me, ‘Well, but you’d never have just UNH students out there running calls, would you?’” says McGregor executive director Bill Cote ’74, who joined the service as a volunteer in 1973. “I tell them, ‘Of course we do. We do that all the time.’ These students are as well trained and well prepared as any service in the country. We have students who serve as crew chiefs, and students who earn their advanced EMT certification. They’re rock stars.”

Rock star Amanda St. Martin ’15 joined the program as a paramedic, certified to deliver the highest level of “pre-hospital” care and one of the only non-volunteer roles at McGregor. Growing up in Coos County’s Whitefield, New Hampshire, she says, “everybody’s dad was a volunteer firefighter,” and she got her start with Whitefield’s fire service as a high school student before finding her place in EMS.

Now in her first year of medical school at Boston University, St. Martin says the EMT class she took as a teenager was the first class she ever loved, and she spent eight years working as a paramedic before enrolling at UNH with an associate degree in hand. Coming into the biochemistry department as a junior, she wasted no time getting involved with McGregor. She put in a full 40 hours a week — going on calls, managing team members’ roles and hiring and training new members — while earning her degree.

A Celebration

50 Years in the Making

Memorial McGregor EMS will mark its 50th anniversary in 2018 with a celebration open to all McGregor/Durham Ambulance Corps alumni. Plans are currently underway; to learn more or to get on McGregor’s email list, contact Chris Lemelin ’06 by emailing

alumni@mcgregorems.org. You can also follow developments on the alumni portion of McGregor’s website: McGregorEMS.org

“We call it the McGregor café,” she says of the organization’s cramped headquarters. “Students hang out there all the time, whether they’re working or not. It’s the nature of a volunteer EMS organization. They’re not there to get paid; they’re there because they want to provide medical care.”

“You Call, We Haul”

Providing medical care hasn’t always been the mandate of EMS, a discipline that didn’t exist in any standardized national format until the late 1960s. It was 1966 when then-President Lyndon B. Johnson commissioned a task force to examine the delivery of “in the field” medical care following a report called “Accidental Death and Disability” that identified accidental injuries as the leading cause of death among younger Americans. The need was pressing; in 1965 alone, car crashes killed more Americans than were lost in the Korean War, and the report concluded that the seriously wounded stood a better chance of survival in the zone of combat than on an average city street.

“Most ambulances were converted hearses, and that wasn’t just a coincidence,” says Patrick Ahearn ’78, a longtime McGregor paramedic/captain and board member who also serves as the organization’s unofficial historian. At the time, he says, any ambulance service a town had was likely affiliated with either the fire department or a funeral home. “The dynamic was pretty much ‘You call, we haul, that’s all.’ The role of ambulance crews was primarily to transport patients to the hospital — or the morgue.”

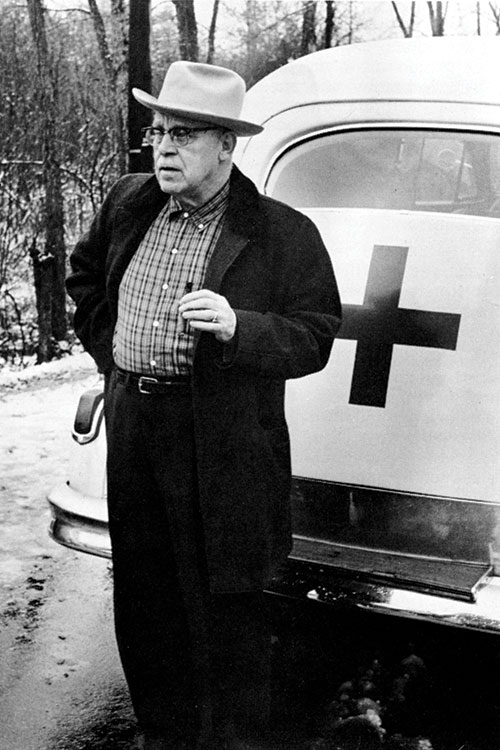

The first standardized national curriculum for EMS was published in 1969, followed by a paramedic curriculum in the early 1970s and soon popularized by the TV show “Emergency!” McGregor came into being in the earliest days of this evolution, formed in February 1968 as a tribute to longtime Durham physician George McGregor. A beloved figure in the community, McGregor had died the day before the annual Durham town meeting a year earlier. “He was a real character,” Ahearn explains. “He was known for strolling downtown in pajamas and a bathrobe, and everyone had a story about him.” At the meeting, townspeople considered a range of memorials, including a statue and a hospital bed at Oyster River High School, before late UNH news bureau director Franklin Heald ‘39 suggested establishing an emergency service in McGregor’s honor. The two men had been on scene at many car wrecks together, Ahearn says, and it seemed like a fitting way to honor the man who had seen many residents into — and out of — this world.

UNH already had an ambulance, a 1959 Cadillac wagon fitted out with a stretcher, a box of bandages and a bottle of oxygen (“not even a regulator or hose for the oxygen,” Ahearn says; “just the bottle”). Following McGregor’s death, a committee was formed and locals raised enough money to upgrade the equipment, and within a year the organization, then known as the Durham Ambulance Corps (DAC), boasted a network of 30 volunteers making 200–300 calls a year out of space shared with the fire department on College Road. The DAC ‘s training and volunteer crew structure soon became a model for other EMS organizations in the state, including those in Newmarket and at Dartmouth. In 2006, DAC changed its name to McGregor Memorial EMS to better reflect the breadth of communities it serves. Two years later, the organization expanded to include the McGregor Institute, which provides EMT training and offers certification in CPR, first aid and babysitting to more than 6,000 people each year.

Today, as McGregor closes in on its 50th anniversary, Ahearn and Cote estimate some 800 volunteers have passed through their organization’s ranks — students, UNH faculty and staff members and townspeople. Some 50 student EMTs have gone on to medical school, and, a more recent phenomenon, another 20–25 have entered physician assistant programs. McGregor alums include former state fire marshal Donald Bliss ’73, ’78G; Lukas Kolm ’88, ’12G, director of emergency services at Wentworth-Douglass Hospital; and Beth Gagnon Daly ’02, chief of the Bureau of Infectious Disease Control at the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services. Michael O’Hara ’10 is a dual resident in pediatrics and anesthesiology at Stanford University Hospital and Lucille Packard Children’s Hospital in Palo Alto, California. Wayne Smith is a senior emergency physician for the U.S. Navy, responsible for the health and medical readiness of the 2nd Marine Division. At one point, the heads of three Seacoast-area hospital emergency departments — Wentworth-Douglass Hospital, Exeter Hospital and Portsmouth Regional Hospital — were all McGregor grads.

Life and Death and Ice Cream

Roughly two-thirds of McGregor’s calls go out in the community — 40 percent to Durham, 20 percent to Lee and 6 percent to Madbury, by Ahearn’s estimates. That means, of course, that a third of calls go to UNH, and McGregor EMTs see a wide variety of emergencies on campus, including those related to drug and alcohol use, mental health issues, sports injuries, seizures and diabetic complications, among others. Far from merely transporting, these student caregivers are trained to operate automated external defibrillators and administer certain classes of drugs. They deliver care to patients in cardiac arrest, victims of assault and massive traumas.

Ahearn and Cote estimate some 800 volunteers have passed through their organization’s ranks — students, UNH faculty and staff members and townspeople. Some 50 student EMTs have gone on to medical school, and, a more recent phenomenon, another 20–25 have entered physician assistant programs.

In her preceptorial, Lockwood and her students discuss these calls, and any time an ambulance goes out on a particularly difficult call — a trauma or a complex medical case involving young children or peers — the team members involved meet as a group to discuss and decompress. Awareness of the potential emotional toll looms large over the group, a shift that Amanda St. Martin says has come about only in the last decade or so of emergency care. “PTSD was definitely a concern in some of my previous jobs,” she notes. “But McGregor has made it a priority to create the necessary support environment for these bright, enthusiastic young student providers that helps them process the tough stuff and go on the next call.”

Particularly as a crew chief his senior year, responsible for assigning roles and duties to his fellow EMTs, Claxton agrees that the work at McGregor regularly took him out of his comfort zone — but it also kept him sane. “When classes were tedious or my research wasn’t going where I wanted, it broke things up and challenged me in ways that were incredibly rewarding,” he says. “I wouldn’t have had it any other way.”

With a 25-year perspective on his own time at McGregor, Navy physician Smith says it’s the experience that’s had the single greatest impact on his career. “I learned not only the technical skills of patient care but also the empathy, professionalism and ethical behavior that is essential in medicine,” he says. For Smith, it’s difficult to imagine an experience that better prepares future leaders to operate independently in a demanding environment so early in their careers. “McGregor provided me with the leadership skills, experience and sense of teamwork that have served me well as a military emergency physician,” he says.

Challenging. Comfort-zone pushing. Demanding. Traumatic. The commitment McGregor requires of its volunteers is extraordinary. Yet so, too, are the rewards of a job that sometimes — but not always — means the difference between life and death.

A case in point: St. Martin recalls one late-night call to a Durham residence for an elderly patient who had fallen in her home. “We were thinking maybe broken hip, because that’s pretty common,” she says, “but it turned out she was just frightened, and she needed help getting back up.” The patient didn’t need to be transported to the hospital — only 60 percent of McGregor’s calls result in transport — but St. Martin and her crew took a few minutes to make sure there wasn’t anything else they could do for her before returning to College Road. “We helped her change into her pajamas and put her in bed, and then just as we were leaving, she mentioned that she really wanted an ice cream sundae,” St. Martin says. The student EMTs didn’t hesitate. They made the patient her ice cream sundae and then were on their way.

Originally published in UNH Magazine Winter 2018 Issue

Comments

WOW! I learned a lot from the article and I'm sure others will too. Congratulations to all involved!

—Marty Thyng ’65

Thank you for the very interesting and well-written article. Its breadth and depth, including interview materials from a wide variety of alumni, its history and examples of invaluable, incomparable preparation for medical school and medical careers was fascinating, illuminating, educational and fun. I especially liked the mention of the life and cute habit of the beloved Dr. McGregor.

—Ingrid Nelson-Stefl

-

Written By:

Kristin Waterfield Duisberg | Communications and Public Affairs