In 1951, the "New Hampshire Midget" watermelon, developed at UNH by Albert F. Yeager, then head of the university’s horticulture department, won a gold medal in the All-American Selection (AAS) trials, the Good Housekeeping-type seal of approval for garden plants. Nearly 60 years later, another UNH researcher was honored by the AAS; J. Brent Loy’s “Honey Bear” hybrid squash was a winner at the All-American trials in 2009.

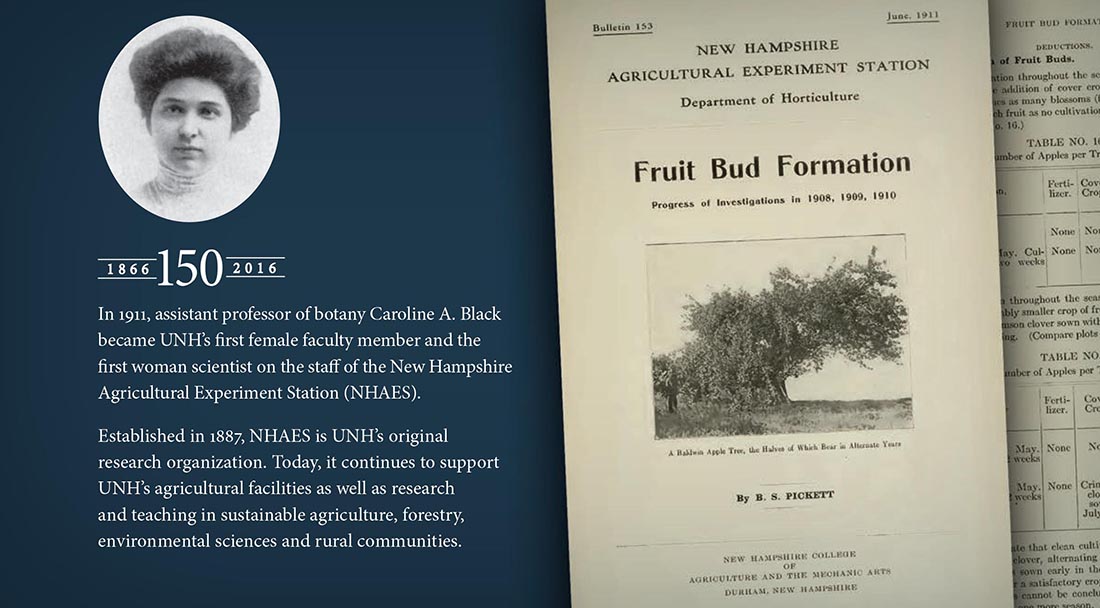

UNH boasts a long legacy of plant-breeding excellence that harkens back to its 1866 founding as an agricultural college. Decades of innovation have brought new crops of watermelons, peaches and even kiwis to Northeast growers and shored up the productivity of traditional favorites like squash and strawberries.

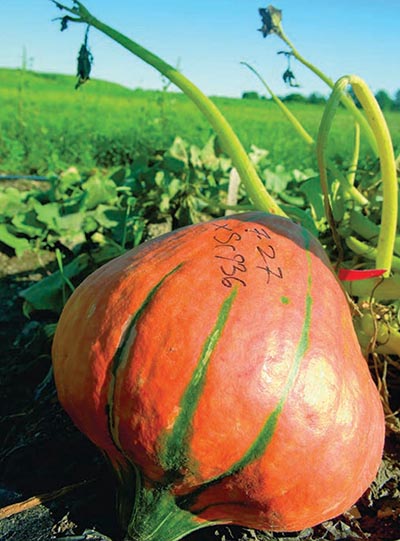

Loy’s is the longest running squash-breeding program in the country. What’s more, his research has resulted in more than 70 new varieties of squash, pumpkins, gourds and melons sold in seed catalogs around the world, with many varieties developed jointly with seed companies located in the Northeast. His most recent work involves grafting melons to hybrid squash rootstocks, a measure that could help extend the melons’ growing season and increase production.

“We’re not the first to get going on this in North America but we’re pretty much right at the forefront,” says Loy, a classically trained plant geneticist and professor emeritus of plant biology.

Iago Hale’s kiwiberry research is another way UNH is shaping the plant breeding landscape. Unlike the more familiar fuzzy kiwi fruit, whose growing season requires 240 days without a frost, the grape-sized kiwiberries are cold-hardy. And while they’ve been growing in New England for nearly 150 years, the tasty, nutrient-rich berries have not been produced on a commercial scale.

Hale thinks that can change. In 2013, the assistant professor of specialty crop improvement planted nearly 200 varieties of kiwiberries at the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station’s Woodman Horticultural Research Farm at UNH with the goal of testing the viability of the vined fruit for regional producers. As word about his program — the only one in the country — has spread, growers have begun to express interest.

“The time is right for this species,” says Hale. He notes that his program is different than those of breeders like Loy, whose work helps keep established producers competitive; kiwiberries aren’t even a true industry yet.

“Globally, there are less than 500 acres in production — probably less than 100 acres in the United States,” he says. “We are trying to domesticate this species and create a new industry where nothing currently exists outside of a handful of novel fruit growers. We have to run through the paces before we ask growers to put their money on the line.”

And he imagines a day when that will happen, as it did for another iconic New England fruit.

“Prior to the 1930s, no one grew blueberries; people collected them from the wild. If you look at New England now, there’s a sizable industry. Potentially, the same could happen with the kiwiberry,” Hale says.

Among breeders, there is always the desire to grow a better fruit or vegetable — to improve productivity, increase disease resistance and develop new and better varieties.

“It’s all very dynamic. There is no agricultural system today that will be sustainable tomorrow. Plant breeding is a never-ending process of responding to current needs and challenges,” Hale says. “There are a lot of organisms in our fields that want to eat our crop plants as much as we do.”

“There is no agricultural system today that will be sustainable tomorrow. Plant breeding is a never-ending process of responding to current needs and challenges.”

Professor Tom Davis, a leading strawberry genetics researcher and professor in the department of biological sciences, calls it an arms race. “Disease-resistant varieties are a better solution than spraying pathogens, which also are always evolving. So, there is always more to be done. It never reaches an end point.”

Davis and his lab members have been using DNA to identify which strawberries have the best genetic makeup to satisfy consumers and growers, with a focus on disease resistance and taste, and increasing the berry’s antioxidant properties while preserving their color.

Meanwhile, post-doctoral researcher Lise Mahoney ’14G has been breeding strawberries with colored petals — reds, pink, even lavender — in addition to the traditional white flowers, adding to their horticultural value.

Next up is looking at the possibility of raising strawberries from seeds instead of plants. “With seed-based varieties, there would be much less uncertainty about the supply of plants, and the concern about importing disease organisms from elsewhere would be eliminated,” Davis says.

Another new project Davis and his researchers are working on is growing quinoa, a high-protein grain native to Peru. Graduate student Erin Neff is researching whether quinoa can be crossed with lambs quarters, an edible wild green, and then grown successfully in New Hampshire.

If they succeed, bringing the “it” grain of contemporary cuisine from the Andes mountains to New Hampshire fields will be the newest fruit of plant-breeding labors planted decades ago at UNH.

colsa.unh.edu/dbs

-

Written By:

Jody Record ’95 | Communications and Public Affairs | jody.record@unh.edu