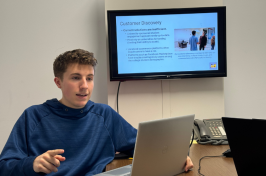

Cameron Wake, research professor and Josephine A. Lamprey Professor in Climate and Sustainability at UNH

Climate has always changed and it always will. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be paying attention. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be doing something, Cameron Wake has said more than once.

Recently the research professor and Josephine A. Lamprey Professor in Climate and Sustainability at UNH has been speaking about what climate change means to New Hampshire. Earlier this month during the talk “Sink or Swim: Facing Climate Change Challenges in Portsmouth,” hosted by Portsmouth Smart Growth for the 21st Century (PS21), Wake noted the “extensive and ever-growing body of scientific evidence” indicating that, over time, humans have the greatest impact on climate change.

“Once you understand that humans are the main driver, you realize the future climate is literally in our hands. The climate that our children and grandchildren inherit depends fundamentally on the decisions we make today and over the next decade,” Wake said.

Calling climate change an innovation opportunity for the 21st century, Wake said it would require the entire globe to solve the problem. “We’re not going to solve it doing the same old thing. We’re going to have to do things a whole lot differently.”

"We have time to figure it out, but we can't wait until 2050, 2080 ... We will need to decide what to spend money on, what to save and what to let go."

Since the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration began monitoring carbon dioxide emissions in 1957, levels have risen from 320 parts per million (ppm) to 400 ppm. According to Wake, if we continue to burn fossil fuels — the biggest producers of carbon dioxide — emission levels will hit 1,000 ppm by the end of the century, creating catastrophic results that would “completely change our relationship with the Earth.” Investing in clean energy and renewable energy could stabilize emissions and hold increases between 450 and 500 ppm.

“We need to figure out how we power our economy and significantly reduce our greenhouse gases,” Wake said, “ and then we need to help the rest of the developing world do that.”

Citing scientists' predictions that use two emission paths — one high and one low — Wake noted there is no reversing the 3 to 5 degree temperature increase we’ll see by 2050 regardless of the path, saying that temperature curve is already “locked in.”

“That’s the amount of warming we’re already committed to,” Wake said.

If emissions stay on the high path, by 2100, temperatures could rise 10 to 12 degrees, creating a climate in Portsmouth like that of North Carolina today. Put another way, those five sweltering days southern New Hampshire averages each year would now jump to as many as 60.

Precipitation will also change based on carbon emissions. Between 1963 and 1972, New Hampshire had one extreme rainstorm with more than 4 inches of precipitation. From 2003 to 2012, there were 10.

“There will be more water falling in fewer events,” Wake said. “As we develop our watersheds, we need to look at how to get more water into the ground.”

As more water falls, sea levels will continue to rise. A report by New Hampshire Coastal Risk and Hazards Commission predicts sea levels in the Granite State will rise between 0.6 and 2 feet by 2050 and between 1.6 to 6.6 feet by 2100.

“Sea levels have been rising and will continue to rise through the end of the century. The only range is how much, by when,” Wake said, adding the projections should be considered when developing the coast.

By 2100, in areas where there are essential structures — schools, bridges and sewer treatment plants, for example — communities should be committed to managing a 4-foot sea level rise but be prepared for up to 6.6 feet.

That increase in Portsmouth would equate to the rise now experienced during a 100-year storm. And that would mean flooding for the vulnerable coast, particularly in the once-tidal waterway known as Puddle Dock in Strawbery Banke that was filled in the late 1890s.

The South End as well as the middle school, the library and the park and recreation fields near the South Mill Pond would also be under water twice a day during high tide.

“We have time to figure it out, but we can’t wait until 2050, 2080 to spend money on things to protect our coast,” he said. “We will need to decide what to spend money on, what to save and what to let go.”

There is some good news for New Hampshire, however: New England will have fresh water, which won’t be the case for many places around the globe, Wake said. “You just have to look at California and the southwest to see examples of that.”

Stressing again the need for everyone to be involved in solutions to curb climate change, Wake said we should not look to the government to solve the problem simply because it is too big. “It’s going to take all of us working together,” he said.

Wake ended his talk on an optimistic note, referencing the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP 21) in Paris where representatives of 195 nations committed to limiting the rise in temperature to 2 degrees Celsius. Wake also cited the Environmental Protection Agency's Clean Power Plan, aimed at reducing carbon pollution from power plants. (Currently under review by the U.S. Supreme Court, the EPA has offered support for those states that choose to move forward with cutting carbon pollution from power plants.)

“More than once I have been called Dr. Doom, but I also love to dance,” Wake said. “And that is the lens I choose to look at this issue with. The storm clouds are gathering, and in some cases are already here, and we need to learn to dance in the rain.”

-

Written By:

Jody Record ’95 | Communications and Public Affairs | jody.record@unh.edu