In Cuba it is called “el bloqueo,” the U.S. embargo against trade and travel that has been in place since 1960. On March 22, during his three-day visit to the island — the first by a U.S. president in 88 years — President Barack Obama was quoted as saying, "the embargo's going to end.” While the dissolution requires Congressional approval, many have begun to speculate what that might mean for the island country, UNH professors among them.

“The embargo should have been lifted a long time ago. I’ve always considered it to be very ineffective and a contrary policy for the U.S.,” says Julia Rodriguez, associate professor of history and a Cuban American whose father came to the U.S. in 1955 in pursuit of opportunity and education. “We trade with China, with Saudi Arabia. If we really cared about human rights, we wouldn’t trade with them, and we’d have travel bans on those countries.”

Many Cuban Americans emigrated here after the 1959 revolution before travel restrictions were tightened. Until 2013, Cubans were not allowed to leave the country without permission.

Julia Rodriguez, associate

professor of history

“Many Cubans have been desperate for open relations with the U.S.,” Rodriguez says.

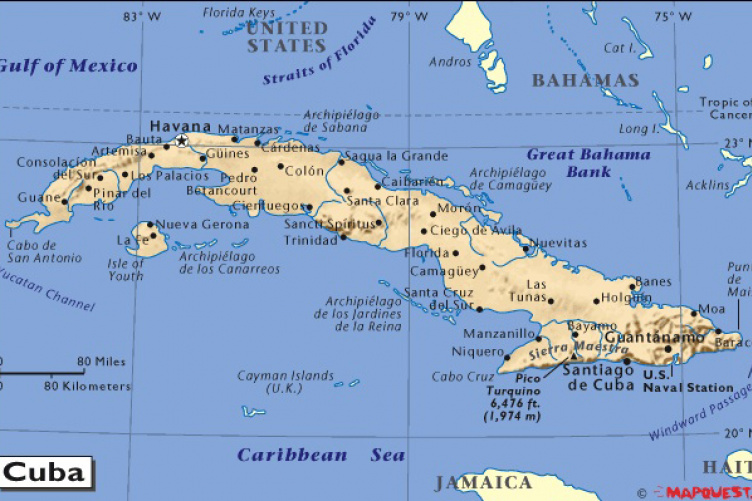

“There are many longstanding Cuban communities here that have existed since the 19th century. When the embargo was put in place, they were abruptly cut off. We’re neighbors, separated by those famous 90 miles. It would be like us cutting off relations with Canada.”

Restoring a connection with Cuba would have a positive impact, says Mary Fran Malone, associate professor of political science, citing the financial benefits as an example. The loss of trade has cost the U.S. more than $1 billion per year during the 55-year blockade. The Cuban government places its annual revenue loss at $685 million.

Lifting the embargo would “increase the amount of trade and U.S. investment in Cuba and also make it easier to transfer money to the island, which would make it easier for Cuban relatives to send remittances back home,” Malone says. How big the impact might be would depend on additional changes the Cuban government might make, she adds, particularly domestically.

“Right now, Cuba is at another crossroads,” Malone says, noting that since the collapse of the Soviet Union, to whom Cuba had turned for support when the embargo was first put in place, the island nation has been in “dire straits economically.”

professor of political science

“Subsidies from Venezuela helped keep the economy afloat. With Venezuela in crisis now, Cuba lost its latest patron. It needs to have major changes in the economy to adapt to changing circumstances, and the lifting of the U.S. embargo would be very helpful to the economy,” she says.

Citing a poll that was conducted last year, Rodriguez points out that the Cuban people are split on “el bloqueo.” “There are those who want a different kind of government,” she says. “And then there are those who think the status quo is OK, who have confidence in their government, who are very patriotic and were raised to equate the revolution with patriotism.”

No embargo would mean more than just free trade and travel, she says. Cubans would have a connection with the outside world in a way they haven’t for a long time. They would learn more about other places, other countries, and how they are run. And that, Rodriguez says, has its own value.

“More open information would help Cubans determine what their government looks like, and what they want it to look like,” Rodriguez says. “And being able to reopen ties and create those connections with relatives in the U.S. — that would be huge.”

-

Written By:

Jody Record ’95 | Communications and Public Affairs | jody.record@unh.edu