With the annual Local Harvest Dinner as the jewel in its locavore crown, UNH is a national leader in bringing local food — some of it grown right here on campus — to the hungry mouths of its students. The efforts are the result of a longtime partnership between UNH Dining and the UNH Sustainability Institute.

While Dining spends more than 20 percent of its budget on items sourced within 250 miles, the Sustainability Institute has an ambition that’s even bolder: Help New England produce at least half of its own food by 2060.

That’s the goal of the New England Food Vision, a collaborative report spearheaded by the Sustainability Institute through the Food Solutions New England regional network it coordinates. It’s the result of the Sustainability Institute’s critical role as a convener and coordinator of people addressing some of the greatest challenges to sustainability.

|

| " I personally LOVE the pumpkin and sage ravioli every year. I also tried the Yankee Farmers honey chipotle chicken, calico mashed potatoes, roasted cabbage, and, of course, the apple crisp," writes UNH Tales blogger Colin Geaghan '16 about this year's Local Harvest Dinner. Read more. |

The way we eat poses one of those challenges. “The whole system we’re in, while it fills up grocery stores with food, it’s not serving us all that well,” says Tom Kelly, founding director of the Sustainability Institute, citing obesity, food insecurity (10 to 16 percent of New Englanders report food shortages), environmental degradation and dollars spent outside the region as among the current system’s troubles. “In fact, it’s driving ill health and lack of profitability for many New England farms and New Hampshire farms. We can do better.”

Published in 2014, the 40-plus-page Food Vision “is a way to look to the future and imagine collectively a future in which our food system is a driver of quality of life, of public health, of environmental quality, of nutritional health,” says Kelly, who was among its nine authors. It emerged from a series of annual food summits, also convened by the Sustainability Institute, that gathered more than 100 “delegates” from six New England states to strengthen regional food system sustainability.

Representing all areas of the food system, these farmers, funders, faculty and food service workers worked together to outline a food system future in which New England produces at least half its food — all of it “clean, fair, just and accessible”— by 2060.

“It’s an aspirational document that speaks to the potential for the future of food in the region,” says report co-author Joanne Burke, the Thomas W. Haas Professor in Sustainable Food Systems. “It helps to build that sense of regional commitment that we can, and should be producing more food for more of our people in New England than we currently are.”

The vision takes a systems approach — essential to achieving sustainability in any realm, Burke and Kelly agree — to proposing a future with far-reaching implications, from how we manage our land to how we eat. By tripling the acres devoted to food production from the current five to 15 percent of the region, or six million acres, New England could boost its production of local food from 10 to 50 percent. The result, say Burke and Kelly, would hedge against political or climate vulnerability that could disrupt global food systems, create a more robust farming and fishing economy and promote healthier eating.

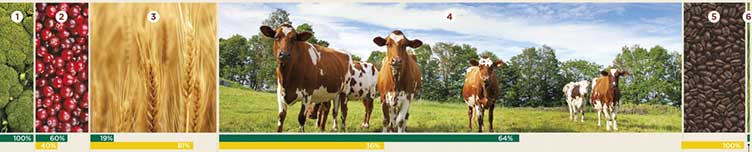

In the "Omnivore's Delight" scenario, New England (green bar) would produce all its own vegetables and 64 percent of its animal products by 2060.

In the "Omnivore's Delight" scenario, New England (green bar) would produce all its own vegetables and 64 percent of its animal products by 2060.Burke, who is also a clinical associate professor of nutrition at UNH, helped develop the central nutritional analysis of the vision, based on an outline of what we will eat and produce in a 50 percent-regional scenario. Called the “Omnivore’s Delight, it has New England producing all its own vegetables, 60 percent of its fruit and 64 percent of its animal products by 2060.

While the Food Vision is just that — a vision, not a mandate or blueprint — it’s gaining acceptance and effecting change. Burke notes that it’s informed both Rhode Island and Massachusetts as those states plan for sustainable food systems that work for all. And while the Food Vision can’t take credit, the number of farms in the region is on the rise, providing clear evidence of New England’s commitment to promoting a regional food future.

Such engaged leadership throughout the region might surprise some who view the UNH Sustainability Institute’s purview as not extending far beyond Holloway Commons or recycling bins in dorms. It shouldn’t, says Kelly.

“UNH has a deep and abiding commitment to sustainability, but we’re also a land-grant, sea-grant institution dedicated to the work that advances the public good well beyond our campus and state. Food systems is a central piece of the public good,” he says.

-

Written By:

Beth Potier | UNH Marketing | beth.potier@unh.edu | 2-1566