Boston is a wicked cool town. It’s got the wicked awesome Red Sox and a wicked hard marathon and wicked fun swan boats in the Frog Pond at the Common, and, according to Urban Dictionary, it is the place where use of the word wicked as an adverb was born.

With that change, says linguistics major Emma Brown, came new meaning. Originally, wicked meant ‘evil or morally wrong’ as in, “By the pricking of my thumbs, Something wicked this way comes.” The Bostonian usage, which Brown says spread through New England, has the term standing in for ‘really’ and ‘very.’

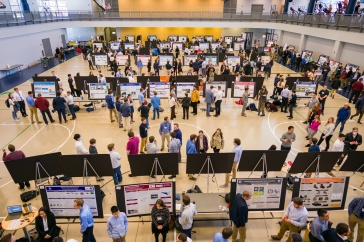

Fascinated with words and the way their use and implication can vary, Brown decided to make ‘wicked’ the subject of her research project for UNH’s 2014 Undergraduate Research Conference. She titled it, “That’s wicked intense: The grammaticalization of ‘wicked’ as an intensifier.”

Historically, Brown says, New England was all one dialect, separated into regions. Eastern New England speech was non-rhoticity—the dropping of Rs following vowels. So, car became ‘cah;’ park, ‘pahk.’ New Hampshire followed suit, evolving to sound like Boston. Using wicked to mean ‘really’ or ‘extremely’ goes back to Eastern New England dialect.

“Wicked isn’t used to mean evil as much anymore; it’s used as a booster,” Brown says. (A booster, like an intensifier, is an adverb that strengthens or amplifies another word, typically an adjective.)

In her research, Brown looked at whether ‘wicked’ has undergone grammaticalization, the process of a word shifting from its original meaning and taking on new context.

An example is the word very. "It’s one of the oldest intensifiers; you can study its use over a hundred years,” says Brown, a member of the Phi Beta Kappa honor society. “Very used to mean truthfully. Now we use it as a booster. The same thing has happened with wicked.”

Brown’s research had her listening to the interviews of 44 people conducted by students in a socio-linguistics class to find intensifiable speech phrases. She found wicked was used as an intensifier 30 times; for example, "It was wicked hot out," "That professor is wicked hard." She also studied Twitter feeds to see how often wicked showed up, searching users by location, subject and keyword. She let the search run for three hours.

“Wicked came up more than 5,000 times,” Brown says.

But some of those mentions were in retweets. Some were in song lyrics. She threw those out, along with song titles and references to the musical “Wicked” and found the word was used 1,500 times.

“It confirmed my spoken word research, “Brown says, adding, “New England speakers would say ‘That’s wicked cool’ while in other parts of the world, they’d say, ‘That’s cool.’”

Leading her to conclude that yes, wicked has undergone wicked grammaticalization. Less formal research revealed the use of wicked as a adjective: "Those are some wicked potholes."

And there is Brown’s own experience, from childhood, of the geographical impact on language.

“I remember when I was little, around 5 or 6 years old, we’d go to visit relatives in Ohio and when I used the word ‘wicked’ around my cousin, saying something was wicked cool, and she’d tell me I couldn’t say that because it was a bad word,” she says. “I said ‘What are you talking about, it’s just a word.’ It’s interesting how different perceptions can be. Wicked is one of those that stands out because it’s such a regional stereotype.”

“Language changes,” Brown says. “We don’t use the same language we did 20 years ago. Some people say it’s due to misuse. Some say it’s culture. Either way, it continues to evolve.”

-

Written By:

Jody Record ’95 | Communications and Public Affairs | jody.record@unh.edu