Ah, the romance of wine. In the Russian River Valley north of San Francisco, it's everywhere. Take a drive on Westside Road, which curves tight as a corkscrew through the vineyards of northwest Sonoma County. Twelve thousand acres of vines nudge the pavement on both sides, standing like ranks of gnarled soldiers with arms flung across each other's shoulders. Around one curve, a canopy of sycamores flashes overhead, top-lit emerald. Around the next, trees yield again to the vine-soldiers, marching endlessly toward the green-gold mountains with the rhythmic name: Mayacama.

Several times each mile, a sign heralds another winery—more than 100 in a 30-mile radius. Shaded driveways meander toward picnic groves, serene terraces, sensual gardens. Tasting rooms beckon from cozy stone farmhouses, cathedral-like converted barns, elegant European-style chateaus. The wineries promise romance with their sweeping views, romance with their esoteric lingo, romance in the seduction of the sip.

Peter Paul's winery isn't one of them. On a spring afternoon with the sky as sapphire blue as his SUV, Paul tackles the curves of Westside Road aggressively, heading home from Grove Street Winery. Not for Grove Street the chateau or the views—or even the vines. Paul's winery occupies two tan sheet-metal buildings on an industrial park drive in Healdsburg. Like many California winemakers, Grove Street doesn't grow a grape. It also doesn't grow an attitude. While other vintners tout "highly nuanced wines of power and finesse," Grove Street puts it simply: "The best wines from Sonoma County for less than $20 a bottle."

It's wine without pretense, a niche Paul has carved in the wine business using the money he made carving a niche in the mortgage business. He loves wine and finds it plenty romantic when he's dining out or stocking the 1,700-bottle wine cellar in his waterfront home. But people who own wineries don't spell wine with a capital R for Romance. In northern California, they're far more likely to list a catalog of C's: chemistry, commerce, community and cooperage.

Upstairs at Grove Street Winery, the aqua-painted workspace of the winemaker looks like what it is: a chemistry lab. Fifty miles separate the winery from Paul's mortgage company, Paul Financial, in San Rafael. But here amid test tubes and beakers, the businessman whose first job out of UNH in 1967 was teaching high school chemistry looks quite at home. Since he bought Grove Street in 1999, Paul has become a student of wine. In discussions of mortgages, everyone defers to him, but at Grove Street he defers to winemaker Mikael Gulyash. For Paul, walking around his winery is a lot like traveling in his Cessna CJ2 jet: "I don't feel I have to fly the plane, but I want to know what the pilot's doing."

Leaning against the counter, Gulyash engages Paul in a discussion of soil acidity and malolactic fermentation—while somehow simultaneously talking about nature and romance. That's the paradox of winemaking: You can see it as a straight-forward process or explore its layers of complexity; you can savor a sip simply as a pleasure or as a complex series of sensory experiences. After nearly 30 years in the business, Gulyash can talk complexities with the best of them. But his philosophy of winemaking is simple: Let nature do most of the work.

THE VINES: Peter Paul '67 checks wine grapes in

the field.

Steps don't come simpler than the basic three of winemaking: pick grapes, crush grapes, let juice sit around. But which grapes? Picked when? Sitting in what? For how long? With what additions? In a time of global grape glut, the answers to those questions can determine whether one wine collects dust while another becomes the toast of the town. Soil, yeast, barrels, blending, time—"those are my cooking spices," Gulyash says. The variations are limitless. Even the untouched grapes offer myriad options, with flavors that conjure up cherry, raspberry, apple, pear—just about every fruit but grape. (Wine grapes don't taste like table grapes.) And each step between vine and bottle changes the wine in fundamental ways.

Take Grove Street's top-selling wine, a 2005 chardonnay. While customers in the winery's industrial-chic tasting room can sip it and simply say "Yum" or "Yuck," Gulyash can narrate its life story: Cool weather in 2005 delayed the harvest, giving the grapes time to develop more sugar without losing their acidity. Though the chardonnay's ingredients are simple (it's a varietal, meaning it's made solely from one kind of grape), its fermentation was complex. Seventy percent of the juice was fermented in steel tanks, 25 percent in wood fermenters, and 5 percent in oak barrels. Gulyash divided the barrels equally between American oak and Russian oak because a different chemical reaction happens with each kind. Only the chardonnay in barrels went through malolactic fermentation (malo rhymes with J-Lo). Bacteria converted the grapes' malic acid into lactic acid, which is less sour and thus lends the wine a softer "mouthfeel."

The quest for the perfect mouthfeel is what gets winemakers out of bed each morning. One expert has developed a "mouthfeel wheel," 53 terms to describe the complex sensations wine creates in the mouth. Few casual sippers will ever use descriptions like grippy or resinous. Even Paul, who says he has evolved from avid consumer to informed consumer since buying the winery, says, "I can't use a lot of those words if I don't have them written on my palm." As Paul chats with another employee in the lab, Gulyash hands him a glass of red wine. It's a blend that's nowhere near finished; its dry astringency puckers the mouth in the same way as drinking too-strong tea. Paul absently takes a sip, then looks up to see Gulyash laughing. Most wine fans know the term for this taste: tannic. Paul has a stronger word as he plunks the glass onto the counter: "Yuck."

Peter Paul enjoys a joke that's older than the bottles in his wine cellar: "How do you make a small fortune in the wine business? Start with a large fortune." Luckily, he did. Headlands Mortgage, the company Paul started in 1986, became one of the nation's top wholesale lenders by specializing in a particular kind of loan. Technically, it's called Alternative A, but Paul spares non-MBA's the details; instead, he spins analogies using sports or food.

When Paul sold Headlands in 1998, the $475 million deal was the largest business transaction in Marin County history. The agreement required him to stay out of the mortgage business for five years, which meant he watched from the sidelines during the hottest part of the real estate boom. It was frustrating—"like retiring just before your team goes to the Super Bowl"—but he kept busy. He worked with the Headlands Foundation, a nonprofit he'd started in 1996 to support local social service groups. He became a major sponsor of the Russian National Orchestra. He built houses with partners. He gave $10 million to UNH. He backed friends' restaurants. He bought a house in Costa Rica. He bought Grove Street Winery.

Making wine may seem completely different from making loans, but to Paul they fit a single quest: making money while having fun. He gets as excited talking about mortgages as talking about merlot; his face lights up as if he's just discovered the fun in funds. Judy Miller, who has worked with him for 20 years, says Paul can expound on a zillion subjects. "You're driving along and you make a stray remark like wondering how deep the bay is," she says, "and 10 minutes later he's still talking about it and he knows."

What he knew about wine might have stopped him from buying Grove Street. "It's a haw-rible business," he booms cheerfully from his desk at Paul Financial, the mortgage company that gives away a bottle of wine with every loan. (Even after 30 years in California, Paul retains a Yankee accent that turns shortly into shawtly.) "You have four or five years of inventory. It takes you so long to get a product out, and then you have only one try to do it." In other words, Grove Street buys grapes but can't know for years what they'll turn into. Meanwhile, markets fluctuate and tastes change. In an optimistic moment, Paul says wines are like restaurants: People have favorites, but they'll still try others. In a pessimistic moment, he says wine stores are like bookstores: If you're not a "name" author, you don't get a prominent place. The name authors of the wine world get rave reviews in Wine Spectator. Though Grove Street wines have won numerous gold medals in competitions, they've yet to become the hot brand.

Together, Sonoma County wineries sell $2 billion in wine each year. But only someone who overindulges in the grape would expect big money from a small winery. Gulyash says the business is a constant struggle to balance quality with demand, and demand can change in an instant. In 1991, a "60 Minutes" segment on the health benefits of red wine caused a huge upswing in sales. In 2004, the movie "Sideways "had a similar impact on sales of California pinot noir. The good news was that Grove Street had a good pinot. The bad news is that it sold out—and when it's gone, it's gone. That particular wine can never be created again.

Musing on the ephemeral nature of pinot is ordinary dinner-table conversation in northern California. "It's a wine society," Paul says. "Everything here connects to wine." Wine is the basis for tourism, the measure of trends, the source of obsession with the weather. Wine is history: Some of the vines along the Russian River have been producing grapes since the 1880s. Wine is news: When California wines beat French wines in a European tasting competition, the victory rates a front-page story in the San Francisco Chronicle. Wine is community currency: Northern California nonprofits rely on wine auctions, fundraising events at which wineries put luxurious dinners and vacations and cases of wine up for bid. Local business people attend and donate to one another's wine auctions in a huge circle that fills both social calendars and charity coffers.

Paul had a wine auction before he had a winery. In its 11 years, the Headlands Foundation auction has raised $3 million for everything from books for pre-school children to a tractor cab for a local food bank. He loves the nonprofit work and the wine community, but during his years sidelined from the mortgage business, Paul missed the financial community. Not making money, he decided, is not fun. Besides, his friends wanted to work with him again.

So in 2003 he started Paul Financial with five employees. Today it has 200, who occupy a building that a friend kept vacant for him. (Most of his stories about business, like most of his stories about fun, begin "I have a friend who ...") Many of the employees have worked with Paul before, or they're related to past or present employees. Judy Miller, who essentially runs his social life as special projects coordinator, is married to Joe Miller, one of Paul's friends from college. The Millers moved to California mostly because Paul made the place sound so good. Gareth Staglin, a fellow winery owner and supporter of local nonprofits, says people often follow Paul's lead. When it comes to charity, Staglin says, "Peter's a Pied Piper of good causes."

On a May afternoon in the chilly warehouse, Paul proposes a tasting tour of wine-in-progress. Gulyash and Grove Street sales director Brent Ferro assemble the necessities: glasses, a bucket for spitting or dumping, a spray bottle of rubbing alcohol, and "the thief," a tool resembling an angled glass turkey baster that sucks wine from barrels and squirts it into glasses. Gulyash presents each pale or ruby liquid for tasting, and a reverent silence reigns before the adjectives begin: creamy, chewy, long finish (and in one case funky, vile, sweaty socks—but that's a local vintner's wine that they're trying to fix). One moment the men sound like engineers discussing the space shuttle, trading terms like oxygen pickup and capsule-to-bottleneck interference. The next, they're fathers assessing their offspring: "For a baby, that's tremendous."

Amid towering racks of oak barrels, they linger to contemplate the mysterious relationship of wine and wood. Wine lovers can talk forever about the flavors—spicy, buttery, vanilla—imparted by barrels of European vs. American oak. Gulyash says the cooper's construction methods affect the wine even more than the type of wood does. Variables include how the wood is aged, how it's split, and especially how it's "toasted." Toasting is using fire to char the inside of a barrel. The degree of "cooking" leads to the barrel's classification as light toast, medium toast or heavy toast; the stenciled letters LT, MT or HT on the ends of the barrels form one more coded message to those in the know.

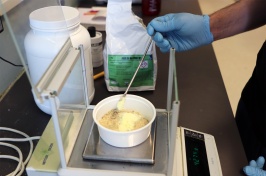

What happens inside the barrels is chemistry, but it's also magic. A small winery's machinery is not magic, and there's surprisingly little of it. At Grove Street, grapes coming off the trucks are weighed and loaded into the crusher, which removes the stems. The rest of the crushed grape, called the must, moves to the press, which gently separates the juice from the seeds and skins. Skins are what give wine color, so white wine gets minimal skin contact. For red wine, the whole crushed grape goes into the fermentation tank; how long the wine sits with the skins determines how dark its color will be.

Fermentation changes the sugar in grapes into alcohol. The yeast that's on the grapes and in the air could make this transformation alone—because, as Gulyash says, "Winemaking is just nature's way of spoiling something." But natural yeast is unpredictable, so winemakers choose from hundreds of kinds of cultivated yeast, each of which adds different tastes and aromas. Fermenting and aging at Grove Street happen in 30 tanks ranging from 1,000 to 28,000 gallons, plus hundreds of barrels holding about 300 bottles of wine apiece. In simplest outline, white wines head out the door about nine months after the grapes came in. Red wines take about two years, which Gulyash says is long in contemporary California winemaking.

After aging comes the bottling line, which Paul calls "the last place you can screw something up." A filler pumps filtered air to clean the bottles, then pumps in nitrogen to eliminate oxygen, the enemy of wine. Wine flows in through a vacuum valve that pushes out the nitrogen. In the next machine, jaws compress the cork so that plungers can force it in. The corked bottle moves to a person, who drops the "capsule"—it looks like a long foil thimble—over the top. Machines crimp the foil and apply the labels. Two minutes after it started filling, the bottle is complete. The work on the line isn't romantic, but it's crucial. In the new wine economy, which Gulyash describes as "monstrously tougher than 10 years ago," some owners believe beautiful surroundings will distinguish a winery; Grove Street doesn't. "All we really need is a warehouse," he says, "because what matters is what happens inside."

Leaving Grove Street, Paul takes the scenic route through the Russian River vineyards. Like the vine flowers, which on this spring day have just begun to set, his life and work are entering a new stage. At about $1 billion in loans last year, "Paul Fi" is still small in industry terms, but he's confident it will find its niche the way Headlands did. The winery is small too, with 16,000 cases sold last year, but signs are good: Recent jazz concerts in the tasting room drew crowds, and two "super-premium" reds are selling well under the Peter Paul label (which, unlike Grove Street, isn't limited to $20).

THE WAIT: The point at which wine has aged

enough is gauged by winemaker Mikael Gulyash,

left, with owner Peter Paul '67.

In his non-work life, his daughter is grown and on her own. At 62, Paul feels young but conscious of time. "I have years, but maybe not 20 years," he says. "I have answered to no one since '86, so I'm probably not employable." That's a joke; he knows he'll never have a boss again. In fact, his challenge now is realizing that his businesses don't need to succeed. "It's interesting to get past the point where it matters," he says. "That's an adjustment."

Ten minutes into the drive, his cell phone vibrates: He's left his briefcase at the winery. "No, don't bring it," Paul tells the caller. "I'll come back." He's been barreling full-speed ahead during this conversation but hangs up and reverses direction. After just a few miles, an oncoming red station wagon flashes its lights. Paul pulls over quickly. Gulyash jumps out, strides over to Paul's car and wordlessly hands the briefcase through the window. Paul drives off again. Later, an attempt at a shortcut will leave him stuck behind a paving crew with his whole body jittering impatiently. Right now, though, the sky is clear, the road is open, and everything's in its place. It's a beautiful day to explore wine country.~

Jane Harrigan is a professor of journalism at UNH.